Collection Gallery

1st Collection Gallery Exhibition 2024–2025

2024.03.14 thu. - 05.26 sun.

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

In this section, we introduce outstanding examples of Western modern art, which are either contained or deposited in the museum collection. In this edition, we focus on works related to Cubism, in particular Albert Gleizes’s Cubist Landscape, Tree and River, which the museum acquired in fiscal 2023.

Cubism was a formal concept advocated by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque at the outset of the 20th century which led to drastic changes in art thereafter. After abandoning unilinear spatial expression, a central feature of traditional perspective and shading in the two-dimensional plane of painting, the artists began experimenting with multilinear pictorial structures based on cubes and other geometrical shapes. This fundamentally upended the notion (which had persisted since the Renaissance) that painting was a reproduction of reality while at the same time greatly expanding the potential for pure visual expression. As it happens, Albert Gleizes (1881-1953) made a significant contribution to the popularization of Cubism throughout the world, both in formal and theoretical terms.

Gleizes was a self-taught painter whose early Impressionist style was influenced by Cezanne. Then, after encountering the works of Picasso and Braque, he set his sights on Cubist expressions. In 1912, Gleizes and a group of like-minded comrades, who placed special importance on color and the principles of dividing the canvas, formed the Section d’Or (Golden Section), and began holding exhibitions. At the same time, Gleizes and Jean Metzinger co-authored Du Cubisme (On Cubism), the first theoretical book devoted to the revolutionary approach. By deepening ideas about both the practice and theory of Cubism, Gleizes was also active in groups such as De Stijl in Holland, Der Strum in Germany, and the Society of Independent Artists in the U.S., played a decisive role in developing and spreading the movement outside of France. In this exhibit, we introduce the book Du Cubisme in a reprinted 1947 edition, which includes prints by eleven artists that were originally scheduled but failed to appear in the original volume.

Gleizes made Cubist Landscape, Tree and River (1914) during a transitional period in which he was moving away from analytical Cubism toward an increasingly planar and more abstract style. A tree towers over the scene in the center of the picture plane. In the background on the right is a row of buildings that appear to be factories with a gray river circumventing them. Despite its robust diagonal structure, the work’s brilliantly colored squares and circles, seen from multiple perspectives, are arranged in a rhythmical manner, expressing the powerful breath of the landscape. The pictorial structure, which conveys a sense of perspective, and the dynamic relationship between the colors and shapes suggest that Gleizes had absorbed the work of the Italian Futurists and Robert Delaunay’s Orphism, perhaps heralding a new phase in Cubism.

Another noteworthy point is that Gleizes’ Cubist Landscape, Tree and River was reproduced in full color in the October 1920 issue of Der Sturm, one of the most important German avant-garde art magazines of the 20th century. At the time, the work was contained in the businessman Adolf Rothenberg’s collection, which was located in the German-occupied city of Breslau (the present-day Polish city of Wrocław). The fact that Gleizes’s Kubismus (Cubism) was published as the 13th volume in the Bauhaus book series indicates that the painting is essential for understanding the acceptance of Cubism in Germany.

Japanese-style Painting in Kyoto and Osaka in the Meiji Era FUKADA Chokujo, Hawk with Waterfall / Mandarin Ducks in Snow, 1895

Although the Meiji Restoration of the late 19th century led to an influx of Western culture, stylistic changes in Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) did not emerge all at once. At the outset of the period, artists were still utilizing techniques that dated back to the Edo Period (1603-1868). The Kyoto art world centered on Kishi Chikudo (of the Kishi school) and Shiokawa Bunrin (of the Shijo school). Mori Kansai, originally associated with the Osaka-based Mori school (headed by Mori Sosen) and known as the “Meiji Okyo” (a reference to the master painter Maruyama Okyo), was also active in Kyoto.

At the same time, literati painting (or Nanga), which was popular in the Edo Period, was still a powerful force, and as suggested by the works of the Osaka-based painters Yabu Chosui and Tanomaru Chokunyu, many artists admired China and took inspiration from Chinese poetry and famous places in the country. After Chokunyu moved to Kyoto, he accepted a post as the first president of the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting, and along with Tomioka Tessai established the Japan Nanga Association.

After the school was founded, figures such as Kono Bairei and Yamada Bunko, who studied with Shiokawa Bunrin, and Okutani Shuseki and Yamamoto Shunkyo, who studied with Mori Kansai, emerged in Kyoto. Also active in the city were artists such as Imao Keinen, Suzuki Shonen, and Kubota Beisen, who studied with Suzuki Hyakunen, an artist who developed his singular style after learning many types of painting, including those of the Tosa and Maruyama-Shijo schools, and literati paintings.

Fukada Chokujo studied with the Shijo painter Morikawa Sobun before moving to Osaka and cultivated a large group of apprentices. The Osaka-based Ueda Kochu (the son of Ueda Kofu, a student of Maruyama Okyo and admirer of Yosa Buson’s style) was known for his skill at making Shijo-style landscapes and flower-and-bird paintings. Kochu’s son Ueda Koho and Chokujo were known for their adroit impromptu drawing, a technique developed by the Sumitomo family to entertain guests, and are believed to have been friends with Mochizuki Gyokkei, who made the same sort of works in Kyoto. Moreover, after being educated in Kyoto, Hada Teruo worked in Osaka and elsewhere for a time. Based on these examples, it is clear that during this era artists moved back and forth between Kyoto and Osaka as well as maintaining friendly terms with other.

Take Your Books, Rally in the Streets——Art of Citation and Reference Dominique Gonzalez–Foerster (1965– ), Untitled (Cinematic), 2013 Installation view, "Order & Reorder" Exhibition, 2016 (Photo: KAWATA Norimasa)

Titled after the painter Tomioka Tessai’s motto, “Read many books, travel many years,” this section focuses on artworks that quote or refer to history, literature, film, and other sources from the past.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s installation, consisting of books stacked up on a green carpet, turns the act of becoming acquainted with books into a work of art. The books, recommended by the artist, are related to movies (film theory, novels that were adopted for the screen, etc.), and viewers are welcome to pick one up and read it on the carpet.

Ana Torfs examines the relationship between film and photography. A man is raising his glass to the word vérité (truth) written on a screen in the light of a slide projector. This is a reference to the line, “Photography is truth. And cinema is truth 24 frames a second,” which was spoken by the protagonist in Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le petit soldat (The Little Soldier). Meanwhile, in Bateau-Tableau, Marcel Broodthaers uses a slide projector to produce cinematic time with a series of still images. Broodthaers, who was also a poet, made some works that deal with the subject of 19th-century literary figures such as Baudelaire and Mallarmé. Here, he spins an abstract nautical tale with close-ups of amateur paintings from the 19th century that depict things like ships, the sea, and a ship’s crew. By imbuing her paintings with temporality, Fukuda Miran reveals the production process that underlies a masterpiece. Here, she breaks Veláquez’s bodegóns down into three stages and, through the use of a lenticular panel, shifts the perspective from right to left.

There are also artists who infuse their works with a unique interpretation of an original work to create a motif. Yanagi Miwa, for example, deals with an innocent girl and her heartless grandmother in Gabriel García Márquez’s novella The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and Her Heartless Grandmother. In Yanagi’s work, a young girl plays both parts, raising questions about preconceived notions of women’s age in fairy tales. In Max Ernst’s A Week of Kindness or the Seven Deadly Elements, the artist meticulously assembled collages of images from 19th-century encyclopedias and prints from illustrated novels. The images depict a variety of cruel acts performed by people with animal heads. In Danh Vo’s work, the letters of a Catholic priest, a missionary in Vietnam during the French colonial era, seem to justify human cruelty in the name of a good cause. Vo asked his father, Phung Vo, a skilled calligrapher, to repeatedly copy the text of a letter that the priest wrote to his own father prior to being executed. As we read these carefully written words, we are naturally reminded of Vo’s own backstory and the political history of Western colonialism. After escaping from Vietnam in a boat during the war, Vo and his family were rescued by a Danish commercial vessel as refugees. Thomas Struth and Dayanita Singh’s photographs of museums and archives convey the idea that documenting and preserving memories of the past for future generations is quite simply a human act.

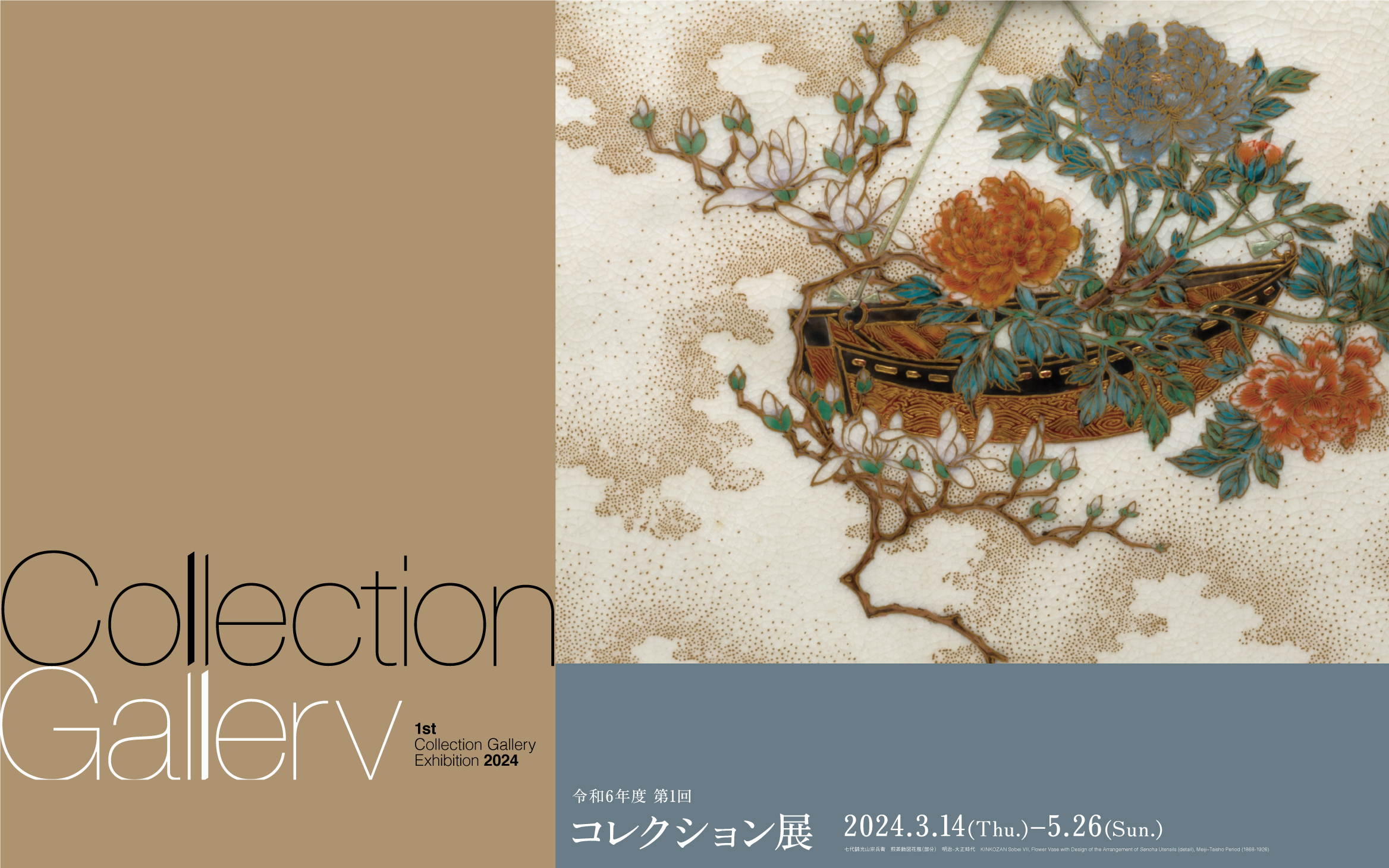

Crafts in the Meiji Era: Tradition and Change KINKOZAN Sobei VII, Flower Vase with Design of the Arrangement of Sencha Utensils, 1868-1926

The Meiji era (1868-1912) was a time of profound change, from the tumultuous fall of the Shogunate to the restoration of Imperial rule and the relocation of the capital to Tokyo, and in the production of crafts, there were major shifts in the dynamics between artisans and patrons. In Kyoto, production under the patronage of temples, shrines, and the Shogunate became moribund, necessitating the search for new markets. Recently, there has been renewed attention to the allure of Meiji-era crafts, produced through division of labor among highly skilled and specialized workers, extending beyond the overseas Japonisme phenomenon to an examination of crafts’ historical significance within Japan.

Kinkozan Sobei VII was an innovator who greatly expanded the overseas export routes initially explored by his predecessor Sobei VI (1824-1884). The Kinkozan family, which had been producing ceramics in Awataguchi, Kyoto, since the Tenpo era (1830-1844), became renowned for their Kyo-satsuma ware inspired by Satsuma Kinrande. They introduced novel techniques, including the application of liquid gold for gold-tinted overglazes and the use of Western paints. Domestic and international expositions served not only as places to exhibit but also as opportunities to learn and improve, and in 1900, Sobei VII personally attended the Paris Exposition with an eye to expanding in the international market.

Demand from overseas markets placed a premium on sophisticated designs. At Kiriu Kosho Kuwaisha, established in 1874, specialized designers and painters devised and applied intricate designs as an organized team. Esteemed artisans such as Shibata Zeshin, renowned for his maki-e lacquer decoration and painting in Edo (present-day Tokyo); his pupil Ikeda Taishin; and Shirayama Shosai were among the participants in this system. While flowers, birds, and scenes of Japanese life were generally favored for export, the imagery – sparrows, swallows, chickens, cicadas, bamboo, willows, gourds – appears classical, while at the same time it reflected the artisans’ enduring values and the breadth of consumer demand. Even as styles of depiction varied, places with poetic associations such as Tagonoura Bay and the Natori-gawa River recurred, perhaps stirring people’s yearning for those locales.

Selected Works of KAWAI Kanjiro KAWAI Kanjiro, Two Figures with a Bird c. 1920

Kawai Kanjiro, a luminary of modern Japanese ceramics, was born in 1890 in what is now Yasugi City, Shimane Prefecture. After graduating from Tokyo Higher Technical School (present-day Tokyo Institute of Technology), he worked as a technician at the Kyoto City Ceramic Research Center, where he devoted himself to research on a vast array of glazes such as celadon and copper red glaze. Having left the research center in 1917, Kawai acquired his own climbing kiln (Shokei kiln) in 1920. The next year he had his first solo exhibition and was highly lauded for pieces inspired by Chinese and Korean ceramics. At the time Kawai was hailed as “like the appearance of new comet in the heavens” and “like a national treasure,” but he was unwilling to rest on his laurels and went on to dramatically change creative directions. Aligning himself with the Mingei (folk art) movement, he emphasized intimate connections between daily life and artistic creation in his ceramics, which grew ever more ambitious and brimmed with the exuberance of living.

The museum’s holdings of Kawai Kanjiro’s works primarily consist of the Kawakatsu Collection, amassed by Kawai’s longtime supporter Kawakatsu Kenichi. This is the premier collection of Kawai in terms of both quality and quantity, and includes his piece that won a grand prize at the 1937 Paris Exposition, is the premier extensive and high-quality compilation of Kawai's creations. As it spans the entirety of his career, it serves as a crucial reference for tracing the evolution of Kawai’s vision and style. The museum has also been fortunate to receive gifts of Kawai’s works outside the Kawakatsu Collection. Here, we present the rich and diverse oeuvre of Kawai Kanjiro through both the Kawakatsu Collection and these additional donations.

Western-style Painters Admired TOMIOKA Tessai

Tomioka Tessai was a self-taught literati painter, deeply versed in Confucianism, Japanese classical literature, and Buddhism, with a unique career that extended well into the modern era. There was remarkable diversity in the reception of Tessai’s work. He lived to be 89, dying in 1924, having been celebrated in the early part of his life as a custodian of ancient scholarly traditions, and later coming to be recognized for unique innovations that him on equal footing with the most forward-looking artists of his era. Nihonga (Japanese-style) painters such as Imamura Shiko, Yasuda Yukihiko, Tsuchida Bakusen, and Ono Chikkyo notably acknowledged the freshness of Tessai’s work, but it was Western-style painters attuned to the latest overseas developments in Western art that most especially admired Tessai.

A prime example is Masamune Tokusaburo, who had studied under Henri Matisse and expressed profound admiration for Tessai, making many visits to Tessai’s residence in Kyoto for guidance. Masamune’s dedication to Tessai was such that towards the end of his life, he published a compilation of his scholarly studies of the master. An oil portrait of Tessai painted by Masamune on the occasion of his death is displayed the beginning of the exhibition Tomioka Tessai: The Last Literati Painter (Commemorating the 100th Anniversary of the Artist’s Death) .

Born in Kyoto and a student of Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Umehara Ryuzaburo praised Tessai’s use of color, stating: “In the near future, historians of Japanese art will remember only a few names: Sotatsu, Korin, Kenzan, Taiga, a number of ukiyo-e artists in the Edo period, and from the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taisho (1912-1926) eras, only Tessai.”

Satomi Katsuzo, also from Kyoto and a former pupil of Maurice de Vlaminck, similarly argued, “The true path for an artist with a soul is the path of Sesshu, Taiga, and Tessai.”

This special exhibit features the works of Western-style painters, including Umehara and Satomi, who were admirers of Tessai.

On a Bicycle: Exploring the Dynamism of Vehicles KOKUFU Osamu, Propeller Bicycle, 1994 (Photo: Seiji Toyonaga)

The era in which Tomioka Tessai (1836-1924) was active coincided with the development of modes of transportation, such as trains and bicycles, which became integral to people’s daily lives. Kyoto Station, opened in 1877, is today a major transit hub that welcomes numerous visitors from elsewhere in Japan and around the world. The oil painting of Kawabata Yanosuke gives viewers a glimpse of how the station looked around a century ago, with the former wooden station building and steam trains in operation. Meanwhile, the dynamism of high-speed trains and the abstract beauty of crisscrossing tracks are vividly captured in the works of A. M. Cassandre, a Ukrainian-born artist active in France, and of the American photographer W. Eugene Smith. These powerful images illustrate the fascination that railways have exerted for numerous artists since the 19th century.

While trains rely on steam or electricity, bicycles are propelled through human effort. There are various theories about the origin of the bicycle, but the Draisine, a two-wheeled vehicle invented in Germany in 1817 that advanced by the rider’s kicking motion, is often cited as the original precursor. By the 1860s bicycles had evolved into mass-produced models with pedals on their front wheels, and the 1890s saw the widespread adoption in Europe and the US of chain-driven bicycles resembling those in use today. Bicycles first made their way to Japan in the late 1860s, and as domestic production ramped up, bicycle ownership rates rose dramatically by the 1930s. That era’s embrace of bicycles is vividly conveyed in the photographs of Nojima Yasuzo and a woodcut print by Taninaka Yasunori, both of which notably feature female cyclists.

Propeller Bicycle by Kokufu Osamu is a work inspired by the early stages of transportation. Kokufu’s somewhat curious vehicles, including this one, echo the innovative functions and designs of Poliscar, a mobile dwelling for the homeless created by Polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko.

In a world where use of energy sources, including those powering vehicles, in pursuit of profit and convenience has often come at the expense of the environment, it is crucial to acknowledge the inseparability of human civilization and nature. Hatakeyama Naoya powerfully conveys the indistinct boundaries between human endeavor and the natural world by juxtaposing images of factory smoke, symbolizing energy consumption, rising into the blue sky like clouds, with the beauty of natural landscapes with vast, limitless horizons. However, unbridled human ambition has tragic consequences, as is starkly evident in events like the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Koie Ryoji’s works, which deteriorate further each time they are exhibited, seem to strongly critique societal and human flaws through a metaphorical act of self-sacrifice.

In the current era, as we grapple with the harsh realities of natural disasters, conflict, human rights and other challenges, Lucy Orta’s clothing-as-shelter emphasizes the need to secure safe havens and uphold the sanctity of personhood. Meanwhile, Takemura Kei's Renovated series serves as a reminder that beauty and resilience can emerge from collapsed and damaged forms, offering a message of hope amid adversity.

Exhibition Period

2024.3.14 thu. - 5.26 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

Japanese-style Painting in Kyoto and Osaka in the Meiji Era

Take Your Books, Rally in the Streets——Art of Citation and Reference

Crafts in the Meiji Era: Tradition and Change

Selected Works of KAWAI Kanjiro

Western-style Painters Admired TOMIOKA Tessai

On a Bicycle: Exploring the Dynamism of Vehicles

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

1st Collection Gallery Exhibition 2024-2025(PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Hours

10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

*Fridays: 10:00 AM – 8:00 PM

*Admission until 30 min before closing.

Admission

Adult: 430 yen (220 yen)

University students: 130 yen (70 yen)

High school students or younger,seniors (65 and over): Free

*Figures in parentheses are for groups of 20 or more.

*This ticket is only available at Collection Gallery.

Collection Gallery Free Admission Days

March 16, 23, 30, May 18, 2024

List of Works 1st Collection Gallery Exhibition 2024-2025(PDF)

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)