About MoMAK

View from the canal to the south of the museum. Photo by Ogawa Taisuke

View from the canal to the south of the museum. Photo by Ogawa Taisuke

Museum Architecture

The streets of Kyoto have been laid out in a grid ever since the nation’s capital was moved here over 1,200 years ago. And Okazaki Park, centered on Heian Shrine and home to The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto (MoMAK), was designed in the Meiji Era (1868-1912) so as to have left-right symmetry. As if manifesting these design principles in its architecture, the exterior walls of MoMAK feature a grid of Portuguese granite and a symmetrical façade, embodying the venerable history of Kyoto.

The museum was designed by architect Maki Fumihiko. Over the more than 30 years since its construction in 1986, we have held nearly 300 exhibitions. However, MoMAK is not only a venue for exhibitions, as many students and architects visit the museum specifically to view the architecture. Here we would like to trace the history of MoMAK, and share some aspects of the building’s particular charm.

A Long-Awaited New Building

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto was established in 1963 as The Annex Museum of The National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. Initially, it was housed in the former auxiliary building of The Kyoto Municipal Exhibition Hall for Industrial Affairs (the predecessor of present-day Miyakomesse), which was renovated and opened its doors as an art museum. The building had been constructed after the 1934 Muroto typhoon, which caused tremendous damage in Kyoto, and was funded by donations and designated as a “museum of commerce” that symbolized the city’s post-disaster resurgence *1. Although it was not originally built as an art museum, the site may have been chosen to house the museum because crafts had been prominent among the goods exhibited there to promote Kyoto industry.

However, when the museum began operating, its quarters were so cramped that parts of the galleries had to be partitioned off and used as storage space. As a result, there were growing calls for construction of a new building, and in 1973 the architect Maki Fumihiko was asked to design it.

Former museum building, photo shows 1978 exhibition L’Affiche en Occident de ses origins à nos jours. Photo by: Konishi Harumi

Former museum building, photo shows 1978 exhibition L’Affiche en Occident de ses origins à nos jours. Photo by: Konishi Harumi

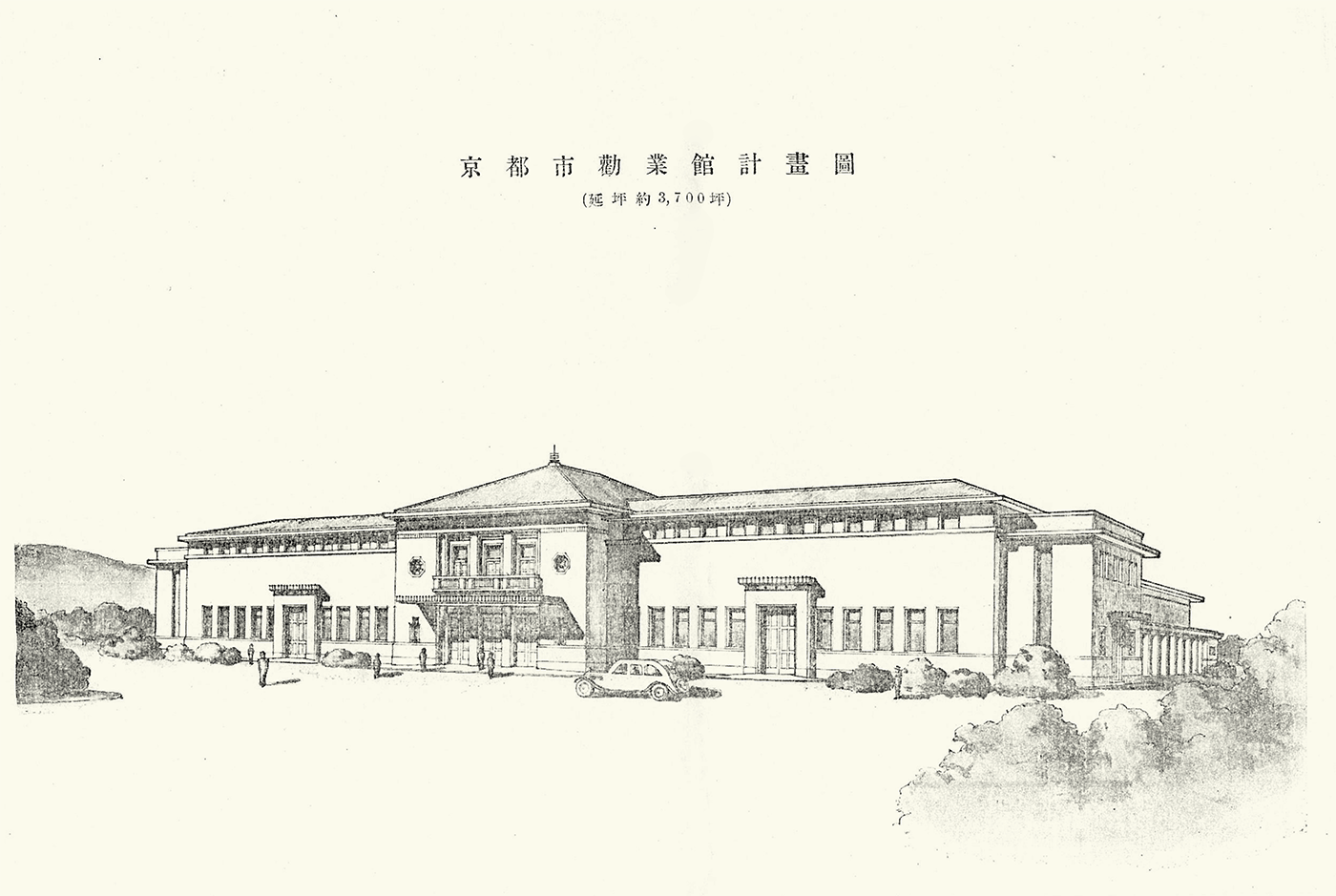

Plan for the Kyoto Municipal Exhibition Hall for Industrial Affairs

Plan for the Kyoto Municipal Exhibition Hall for Industrial Affairs

*1. Source: “Records of the Kyoto Municipal Exhibition Hall for Industrial Affairs Reconstruction Project Sponsorship Association,” Kyoto Municipal Exhibition Hall for Industrial Affairs Reconstruction Project Sponsorship Association (ed.), 1935

Architect Maki Fumihiko Designs a New Face for the Community

The world-renowned architect Maki Fumihiko is a recipient of the Pritzker Prize, often regarded as the Nobel Prize of architecture, and the Gold Medal of the International Union of Architects. Since his first Japanese project, the Toyoda Auditorium of Nagoya University, he has designed many renowned buildings including Spiral (Aoyama, Tokyo) and 4 World Trade Center (New York City). His Daikanyama Hillside Terrace, which over the course of nearly 30 years emerged as a structure that reshaped the image of Tokyo’s Daikanyama district, is an example of one of his projects that has altered the urban landscape through architecture. Maki’s works have consistently addressed the history and culture of the cities where they are built, creating new faces for these communities.

Serene Scenery Preserved: Museum Lower than Grand Torii Gate of Heian Shrine!

Okazaki Park, where MoMAK is located, was originally developed during the Meiji Era as a venue for the National Industrial Exposition. With this historical background, the nature-rich urban oasis and Kyoto cultural center ringed by the Lake Biwa Canal has been officially designated as a scenic area so as to preserve its beauty.

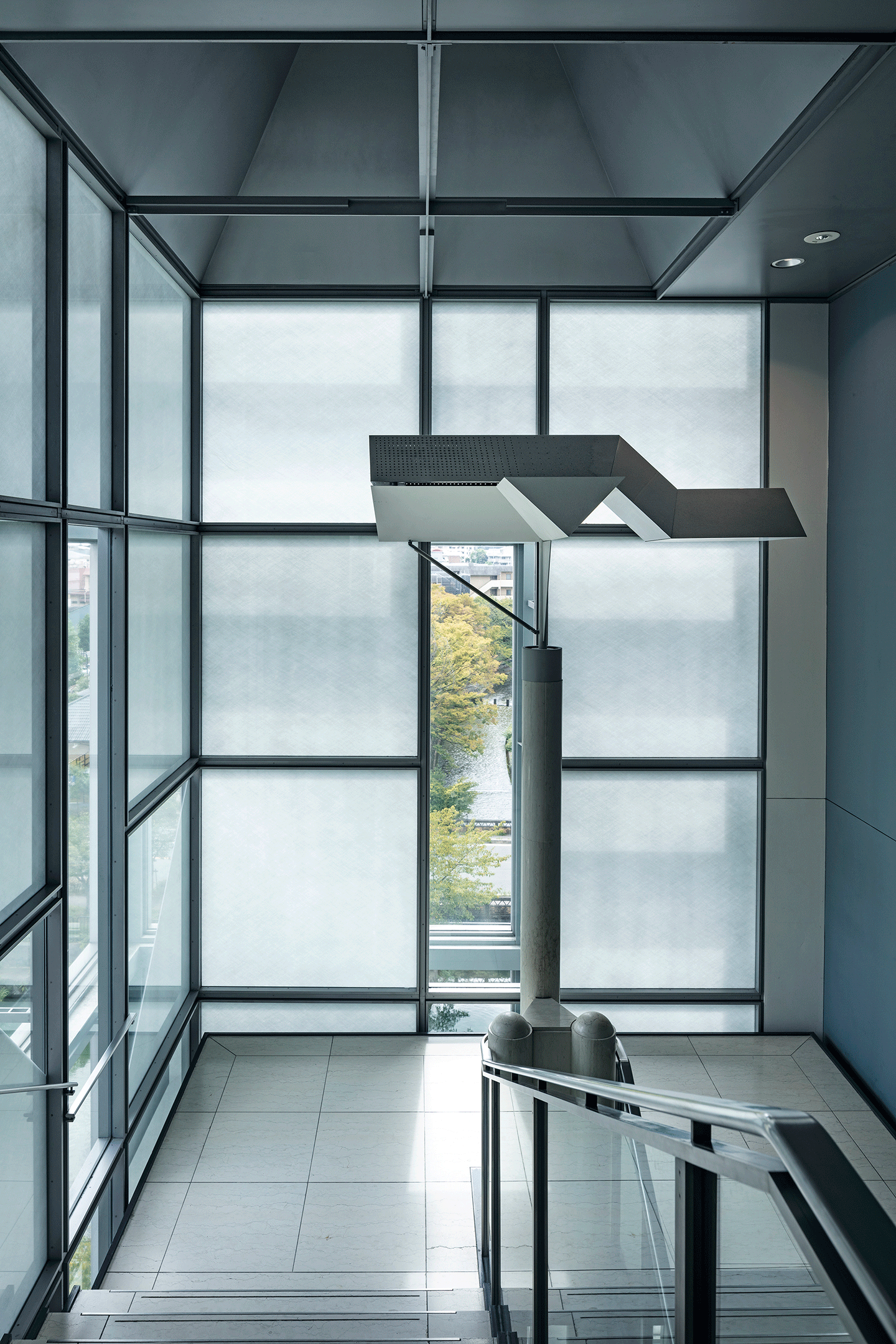

For this reason, in the park, construction of buildings taller than the grand torii gate on the approach to Heian Shrine is not permitted. However, thanks to various ingenious design ideas, the museum has an expansive, spacious feel. For example, the floor area on the second floor is reduced, giving the entrance area and lobby higher ceilings. Also, the large stairway facing visitors when they enter the museum features skylights that let sunlight in from above. In addition, the rear lobby has a series of large windows offering lovely views of the canal.

There are also glass-walled staircases in all four corners of the museum. Sunlight is not allowed to enter the galleries, in order to conserve the works, but upon stepping out of the galleries one immediately encounters a panoramic view of the outdoors that alters one’s mood––another distinctive feature of the architectural design.

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto under construction.

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto under construction.

Materiality of Stone, Glass, and Steel Emphasized

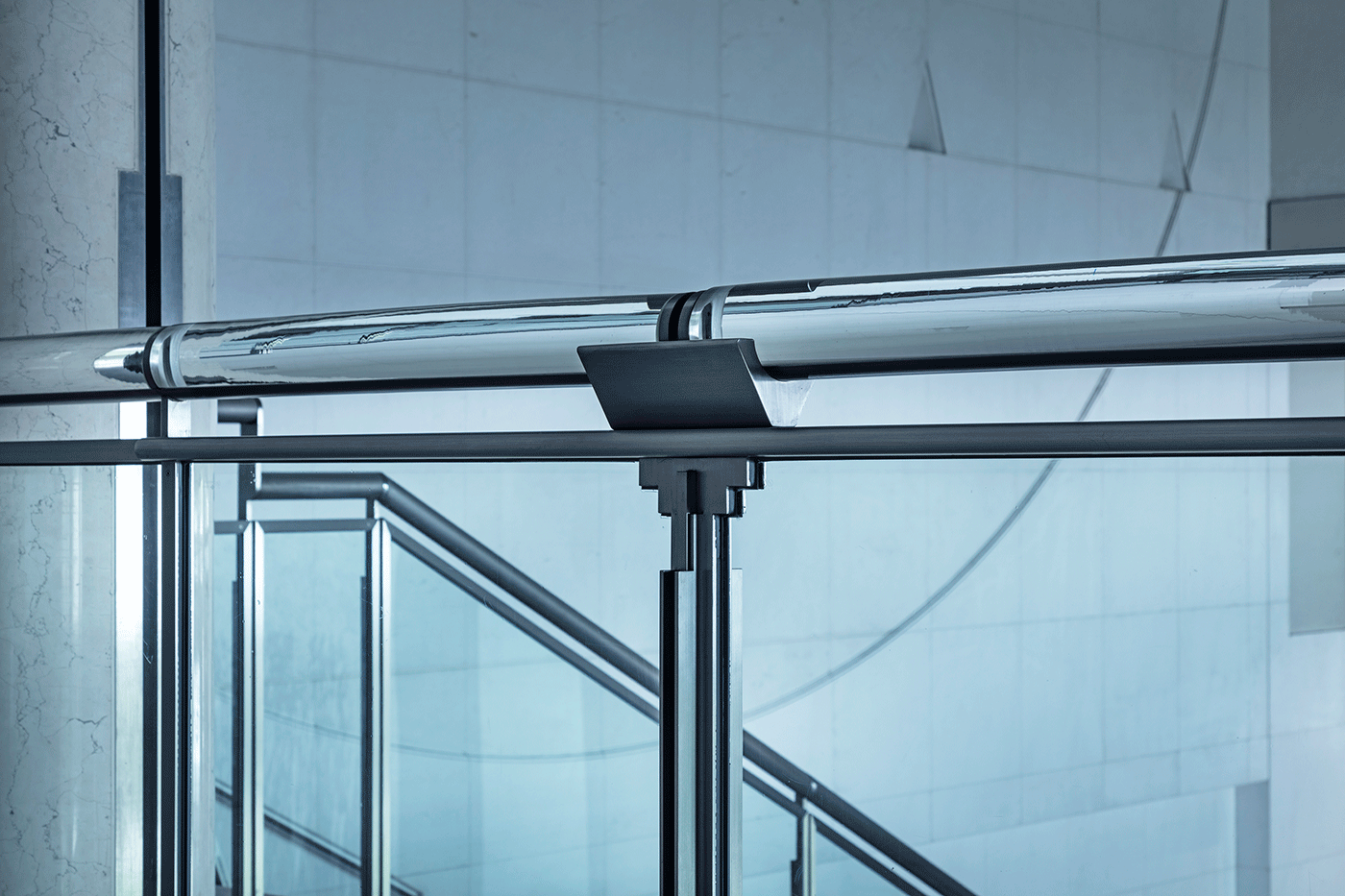

The museum building makes extensive use of varied materials: stone, glass, steel. The outer wall is made of Portuguese granite. Its gray, textured surface is imposing, but on stepping inside, visitors encounter a radically different white marble space. As they walk further and encounter the stairs, they find railings made from a combination of steel and glass.

Another notable point is that the staircase columns are colored vermilion or gray. Architect Maki said, “I intend to create a seemingly ‘De Stijl’ world.”*2 Among the works in the MoMAK collection is Composition (1872-1944) by Piet Mondrian, leader of the De Stijl group, and at the museum visitors can experience a world such as Mondrian envisioned.

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto stairway rails. Photo by Hasegawa Kenta

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto stairway rails. Photo by Hasegawa Kenta

*2. Source: “The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto,” Shinkenchiku, January 1987.

Glass Screens Soften Incoming Light

The museum’s windows are of two types, clear glass and milky, translucent glass. They offer panoramic views of the outdoors, and let in external light, while softening the sun’s rays and protecting the museum from direct sunlight. The translucent glass is of a special formulation, with white glass fiber sandwiched inside it, and is reminiscent of Japanese shoji screens.

Stairway / Glass façade. Photo by Hasegawa Kenta

Stairway / Glass façade. Photo by Hasegawa Kenta

Furniture Specially Designed to Highlight the Museum

Distributed throughout MoMAK is furniture designed especially for the museum. For example, a purple bench resembling a ribbon, by furniture designer Fujie Kazuko, is placed in the center in front of the Collection Gallery. Designed especially for the museum, this is among the earliest works by Fujie, who is now internationally active and widely acclaimed.

There are many other pieces of furniture bringing vivid life to various corners of the museum, such as shop and café counters and oval tables in the information area.

Furniture by Fujie Kazuko. Photo by Hasegawa Kenta

Furniture by Fujie Kazuko. Photo by Hasegawa Kenta

Versatile, Multi-purpose Lobby Space

Over the more than 30 years since it was completed, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto has been the venue not only for exhibitions but also for a variety of events such as concerts and dance performances. As the role of art museums continues to diversify, sites like this one, which accommodate a wide range of uses, are of the utmost value.

The lobby space overlooking the Lake Biwa Canal is one that powerfully conveys the architectural vision of The Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto.

Live Performance: “Noiseless/Soundless,” 2007

Live Performance: “Noiseless/Soundless,” 2007

(Motohashi Jin, Assistant curator)