Collection Gallery

2nd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2023–2024

2023.07.13 thu. - 10.01 sun.

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

In this area, we present outstanding works of Western modern art from our collection or entrusted to the museum. The current term features works by Joan Miró, which relate to the exhibition The Sodeisha Group: An Era Born Out of Avant-garde Ceramics concurrently on view in the special exhibition gallery on the third floor.

Born in Barcelona, Spain, Joan Miró (1893-1983) was a painter who also worked in sculpture and ceramics. He is widely known for a style that utilized automatism, a central technique of Surrealism, and his works are characterized by undulating images between figurative and abstract elements, unrestrained lines, and vivid colors. There are many connections between Miró and Japan, which were comprehensively and extensively showcased in the exhibition Joan Miró and Japan held last year at the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art and elsewhere.

À toute épreuve (Ready for Anything) is a set of poems (first published in 1930) by Paul Éluard, for which Miró created illustrations. The text consists of two sections, “Universe-Solitude” and “Confections,” and contains 52 short poems. Against the backdrop of a turbulent world situation amid the Great Depression and Éluard’s unhappy relationship with his wife, his poems express feelings of despair and isolation. However, Miró’s illustrations, which incorporate techniques such as frottage and collage into woodcuts, are brimming with warmth and humor as if to comfort his friend. The proposal to collaborate on this project was extended to Miró in 1948, but with 233 woodblocks required to produce the 80 illustrations, it took a decade to complete. In fact, in the midst of his work on these woodcuts in 1952, Imaizumi Atsuo, the first director of this museum, visited Miró and reported on his progress: “He was making prints of the woodcuts he had made, which he intended to publish in Geneva. The woodblocks resembled cherry wood, and he was working with a rounded chisel like those used in Japan.”

Miró began producing ceramic works in 1942 after visiting an exhibition of ceramics by his old friend Josep Llorens i Artigas in Barcelona. The ceramic sculpture Project for Monument is one of over 200 ceramic pieces created in collaboration with Artigas and his son, who shared a strong interest in Chinese and Japanese pottery. From 1951 onwards, Miró sporadically produced a series of works titled Project for Monument, not limited to ceramics but also incorporating wood, iron, and bronze. Only a small fraction of them actually evolved into large-scale monuments. The head in this work, resembling stacked ceramic fragments, is the same as that of the original sculpture for Solar Bird created in 1945. However, this part alone was enlarged with marble and bronze in 1966. In creating these monuments intended for outdoor installation, Miró intended for the work to become part of the landscape, seamlessly integrated into nature.

Miró first visited Japan in 1966. The occasion was his large-scale show Joan Miró Exhibition―Japan, 1966, held at The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, as well as at this museum, which was its annex at the time. During his stay Miró also came to the Kansai region, visiting Katsura Imperial Villa and Ryoan-ji Temple in Kyoto. He also attended Exhibition of Keisen Tomita at this museum, and visited Shigaraki to observe Shigaraki ware. The ceramicist Yagi Kazuo accompanied Miró during the Kansai portion of his trip.

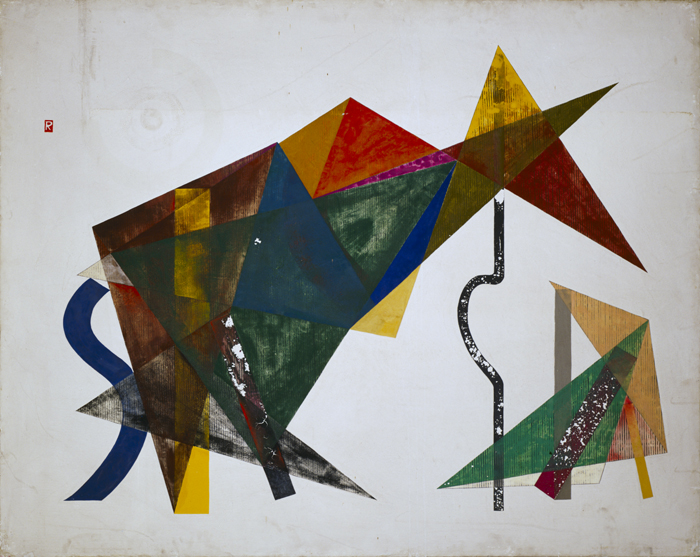

From Rekitei Art Association to Pan-Real and Pan-Real Art Association YAMAOKA Ryobun, Spannung, 1938

Rekitei Art Association (referred to below as “Rekitei”) was formed in April 1938 by nine members: Iwahashi Eien, Taguchi Sakan, Baba Kazuo, Funada Gyokuju, Yamaoka Ryobun, Hamaguchi Yozo, Tsuda Masachika, Sanyu, and Shinomiya Jun’ichi. Takiguchi Shuzo, who played a central role in introducing Surrealism to Japan, coined the name Rekitei and designed the group’s logo. Yamazaki Takashi of Kyoto participated in the First Exhibition of “Trial” in March of the following year. In the sixth exhibition Yamazaki invited the ceramic artist Yagi Kyohei (Yagi Kazuo), a neighbor of his, to exhibit as a guest member, and Yagi participated until Rekitei’s eighth and final exhibition. The members of Rekitei produced experimental works employing a variety of techniques, including frottage, decalcomania, and photograms. One breakthrough was the use of formaldehyde solution in Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) to harden the surface and render it water-resistant, and this technique was subsequently carried on by the Pan-Real group and paved the way for a diverse range of works. Rekitei faced challenges including constraints on creative freedom under the wartime regime, but with offices in both Kyoto and Tokyo, they were active nationwide and garnered much attention. In 1943, Rekitei came to an end when it was integrated into Nihon Sakka Kyokai along with the groups Bijutsu Shinkyo and Meiro Bijutsu Renmei.

Yamazaki Takashi, who had left Japan in 1942 when he was conscripted into the military, was demobilized in 1946 and connected with Mikami Makoto, and this became the catalyst for formation of Pan-Real. Their initial intent was to revive Rekitei. The Rekitei exhibitions had accepted submissions without limiting them to categories such as Nihonga, Yoga (Western-style painting), collage, sculpture, photography and so forth, and they aimed to preserve this approach and establish a group that spanned genres. As a result, eight members formed Pan-Real in 1948: Nihonga painters Mikami Makoto, Yamazaki Takashi, Hoshino Shingo, Fudo Shigeya, and Tanaka Susumu (Tanaka Ryuji); Yoga painter Aoyama Masakichi; and ceramic artists Yagi Kazuo and Suzuki Osamu. The name Pan-Real signified “all that is real,” and Yamazaki asserted that “all straightforward expression of emotion is real (regardless of whether it is figurative or abstract).” After the Pan-Real exhibition was held at Maruzen Gallery in Kyoto, Yagi and Suzuki withdrew to form the ceramics group Sodeisha and Aoyama also departed, solidifying the group’s identity as a Nihonga collective. Then, with the addition of Ono Hidetaka, Shimomura Ryonosuke, Suzuki Yoshio, Matsui Akira, Ogo Ryoichi, and Sato Katsuhiko, the group got a fresh start as Pan-Real Art Association in 1949.

Rekitei, Pan-Real, and Pan-Real Art Association shared the common goal of breaking free of old-fashioned conventions and exploring new horizons in Japanese art, but Rekitei and Pan-Real Art Association differed in that while Rekitei retained the traditional motifs summed up as “flowers, birds, wind, and moon,” Pan-Real Art Association distanced itself from these motifs and sought freedom from the constraints of traditional Nihonga. This is exemplified by the prevalence of folding screens in the works of Yamaoka and Yamazaki from Rekitei, whereas Pan-Real Art Association works are primarily framed, indicating a difference in artistic vision. This can be attributed in part to the eras when the groups were active, during wartime and in the postwar years respectively, as well as to the fact that as a Nihonga group, Pan-Real Art Association was focused on concerns relating specifically to the nature of Nihonga.

Fragile: Restoration, Healing, Regeneration TAKEMURA Kei, Renovated: Dish with Plums, 2021, Photo: Natsumi Kinugasa

The word FRAGILE appears on stickers affixed when shipping delicate items. In the realm of art, there are physically fragile and vulnerable works that require careful handling, as well as works that take various aspects of vulnerability as their theme.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, originally from Cuba, used everyday objects and language as materials to create fluid and variable works without a fixed form, challenging the prevailing notion that works of art derive their value from uniqueness. One of his works, “Untitled” (Dream), features a snapshot printed on a jigsaw puzzle rather than photographic paper. The image is of handwritten text including the phrase “those silly dreams fade,” and the work juxtaposes the ephemeral nature of dreams that disappear upon waking with the transience of a photographic image reducible to scattered fragments.

Takemura Kei affirms the reality of everyday objects’ fragility, and takes this as a starting point for production of new works. In her Renovated series, she uses durable silk thread to mend broken items, such as tableware and toys, by wrapping them in white organza fabric. She then uses silk thread to apply subtle embroidery that traces the marks and scars left on the objects.

There are times when people, too, are in need of “renovation,” for which we might substitute the word “healing.” In Pipilotti Rist’s Heilung [Healing], computer-generated footage of organs and red blood cells during surgery appears on monitors attached to the sides of a first-aid kit, conveying the experience of a body undergoing treatment.

Other artists create new works from discarded or overlooked materials. Fukumoto Shioko breathes new life into old Tsushima linen kimono, part of the cultural heritage of Tsushima Island in the Genkai Sea near Kyushu, by transforming them into powerful indigo-dyed tapestries. Meanwhile, Fiona Tan projects and thereby resurrects archival ethnographic films. In this work, the images of fragile infants being wrapped in fabric evoke the fundamental nature of the way we relate to the delicate and defenseless.

Avant-Garde Textiles in the 1960s: Shimura Mitsuhiro, Nakano Mitsuo, Asada Shuji, Tajima Yukihiko ASADA Shuji, '68-D, 1967

In the field of textiles, the 1970s saw the emergence of freeform “fiber work” that treated fiber like a sculptural material. Prior to this, as with other craft genres, the Nitten (Japan Fine Art Exhibition) served as the primary forum for presentation of works, with craft associations such as the Japan Kogei Association and Shinshokai also playing a prominent role. However, within the art scene as a whole, a series of avant-garde groups emerged in the postwar period and advocated new venues that were alternatives to, or even adamantly opposed to, the officially sponsored exhibitions, holding numerous independent exhibitions open to all. In this context, in Kyoto, graduates of Kyoto Municipal Hiyoshigaoka Senior High School (present-day Kyoto City Senior High School of Art) and textile design majors at Kyoto City University of Arts (one of the precursors of the present-day Kyoto City University of Arts) formed the textile group Dandara in 1958, seeking opportunities to exhibit their works freely. The group held exhibitions at Kyoto Shoin Gallery, with Shimura Mitsuhiro and Nakano Mitsuo participating from the third exhibition onward and Asada Shuji in the fifth exhibition. Dandara disbanded after the fifth exhibition closed, and the following year the dyeing artists group “∞” was formed, clearly positioning itself in opposition to open-call exhibitions. While Nakano elected to exhibit with the Shinshokai association and did not join the new group, Tajima Yukihiko, who had been a younger schoolmate of Asada’s at university, became a member, and ∞ was launched as a collective of five artists, including Shimura, Asada, and Tajima. Until its dissolution in 1973, ∞ maintained a stance of filling exhibition venues with innovative works that explored the possibilities of dyeing. Each of the members established their own unique style: Shimura focused on the repetitive nature of stencil dyeing technique, using utsushi nori (a mixture of dye, starch, and fixative) to investigate the expressive power of color, while Asada’s stencil dyeing featured vividly colored, overlapping geometric shapes, and Tajima used logwood dye to create narrative-driven works inspired by folktales. Meanwhile, Nakano, who continued to exhibit with Shinshokai, produced works during this period that utilized simple shapes, arranging shapes and combining colors to generate a wide range of visual effects.

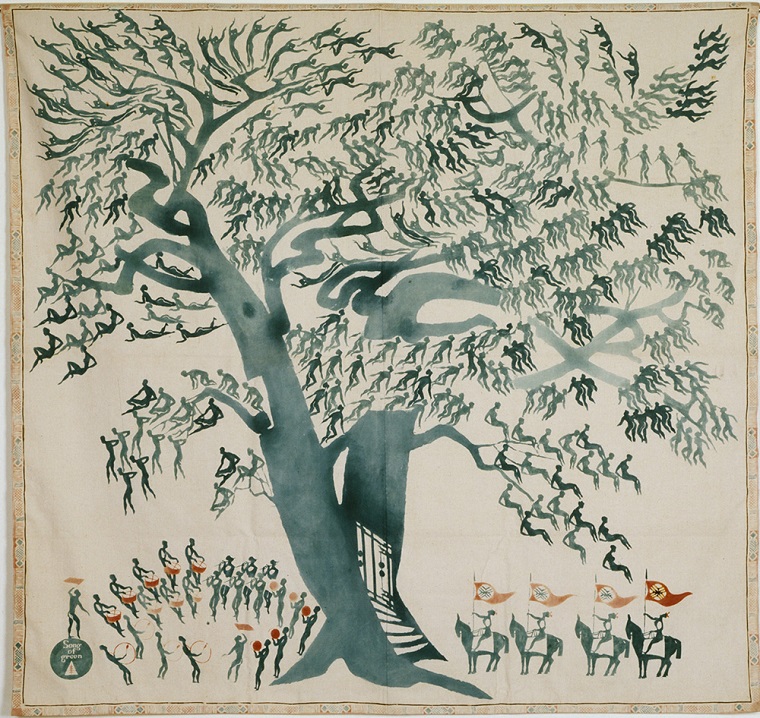

A Postwar Craft Association: Shinshokai INAGAKI Toshijiro, Tapestry, Song of Green, 1956

In Japan, the period beginning with Japan’s 1945 defeat in World War II and continuing until the present day is commonly referred to as “postwar.” Very early in the postwar era, in 1947, Shinsho Bijutsu Kogeikai (New Craftsmen Arts and Craft Society) was established (it later changed its name to Shinshokai, and to then to Shinsho Kogeikai in 1975). The society was formed when Tomimoto Kenkichi withdrew from Kokugakai (The Association for the Creation of National Painting), and other artists who admired Tomimoto also left Kokugakai to found a new craft association. Notable participants included textile artist Inagaki Toshijiro and ceramic artists Tokuriki Magosaburo and Fukuda Rikisaburo. The following quote from its founding document conveys the enthusiasm of the time:

Now is the time for us to burst out of our old shells, and to shoulder the solemn responsibility for reconstruction of a new Japan that is imposed upon craftsmen. We believe that our true and righteous path forward is to grapple with the needs of everyday life from our unique perspectives and with a greater degree of freedom, and in this spirit we embark upon a new journey today.

In 1951, following the withdrawal of artists from the Nitten (Japan Fine Art Exhibition), which played the role an official government-sponsored exhibition, the group reorganized and renamed itself Shinshokai. It can be said that this restructuring had the effect of clarifying the association’s nature. In a text titled “Impressions of Shinshokai,” the ceramics researcher Naito Tadashi likened works exhibited by Shinshokai to “friends dressed in casual attire.”

Tomimoto and Inagaki, both charismatic figures in the group, died in rapid succession in 1963, but Shinshokai soldiered on. Members included Isa Toshihiko, who was drawn to the group by Tomimoto’s creative stance and, after joining, was captivated by Inagaki’s stencil technique and subsequently moved away from traditional wax-resist dyeing and embraced new methods; and Nagao Norihisa, who studied under Inagaki at Kyoto City University of Arts (one of the precursors of present-day Kyoto City University of Arts) and later relocated his base of activities to Okinawa as a professor in the crafts department at Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts, where Isa was also employed. They and many others directly or indirectly influenced by Tomimoto and Inagaki presented innovative works within the context of Shinshokai.

Over the many years of the Japanese postwar era, people have sought changes to existing value systems, with varying degrees of urgency that may depend on their field of activity and individual perceptions. However, one constant has always been the need for spaces for unrestrained artistic creation and the presentation of the resulting works to the public.

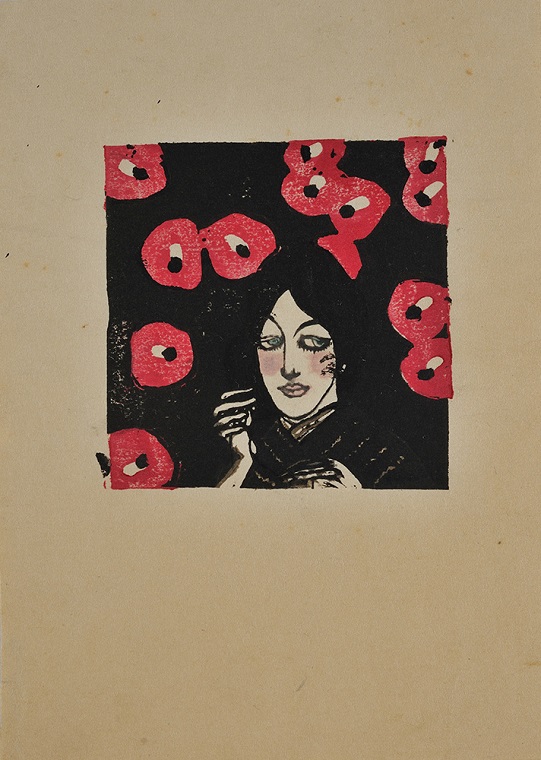

An 'Avant-garde' Era of Japanese Western-Style Painting ONCHI Koshiro, Title Lost, 1913

The history of Japanese modern art got fully underway when artists began learning and drawing inspiration from nearly contemporaneous Western modern art. If we view the basis of modern art as confrontation with, and transcendence of, the art of the past, then the avant-garde is a constant presence. The French word avant-garde originally referred to the vanguard of a military force on the front lines, and in terms of the history of Japanese modern art, those who first attempted oil painting or incorporated Impressionist style were undoubtedly avant-garde painters on the front lines in their day.

However, when we speak of the avant-garde in modern art, we are often referring to more recent developments such as Abstractionism and Surrealism. In Japan, after Cubism was introduced (it was initially known as “Anti-Naturalism”) in 1912, the shinko bijutsu (“new emerging art”) movement, which included Futurism and abstraction, began gathering steam. One significant milestone in this story was the formation of the Futurist Art Association by Fumon Gyo (1896-1972) in 1920. Subsequently, new groups such as Action and Mavo appeared which brought in members from a range of disciplines, who were engaged not only in visual art but also in various other fields including literature, theater, music, and architecture, leading to the further expansion of the avant-garde.

By the end of the Taisho era (1912-1926), the avant-garde had temporarily subsided and its energy had been absorbed into political activities. However, in 1930 the Independent Art Society (Dokuritsu Bijutsu Kyokai) was formed primarily by Fauvist painters who had withdrawn from the Nika group. The new society attracted painters inclined towards the surrealistic and fantastical, reigniting avant-garde visual art. Meanwhile, abstract painters gathered in the Nika group, while other forward-looking painters formed the Free Artists Association (Jiyu Bijutsuka Kyokai). Also, some Surrealism-influenced artists left the Independent Art Society to establish the Bijutsu Bunka [Art and Culture] Art Association. In this manner, Japan’s vibrant avant-garde endured through wartime repression and laid the foundations for postwar art.

Here, we present works from our collection by avant-garde-oriented painters of the Taisho era and the prewar years of the Showa era (1926-1989).

Special Feature: 100 years since the Great Kanto Earthquake

Ikeda Yoson’s Sketches of the Great Kanto Earthquake IKEDA Yoson, Sketches of the Great Kanto Earthquake, 1923

Ikeda Yoson (1895-1988) was born in his father’s home prefecture of Okayama and moved in 1910 to Osaka, where he studied at the Tensaigajuku art school under the Yoga (Western-style) painter Matsubara Sangoro. However, an encounter with Ono Chikkyo led him to shift to Nihonga (Japanese-style painting), and in 1919 he enrolled at Takeuchi Seiho’s Chikujo-kai school. The same year, his work was selected for the 1st Teiten (Imperial Fine Arts Academy Exhibition), and subsequently he primarily showed work in official exhibitions such as the Teiten, the reformed Bunten (Ministry of Education Fine Arts Exhibition), and the Nitten (Japan Fine Art Exhibition). He was also highly dedicated to educating younger artists at the Kyoto City Technical School of Painting and at his own art academy Seito-sha. His works feature landscapes captured from unique angles and charming depictions of animals. In his later years he became a devotee of the poet and author Taneda Santoka and embarked on the Santoka series of paintings based on the latter’s haiku, and in 1987 he was honored with the Order of Culture.

At 11:58 am on September 1, 1923, four years after Yoson became a pupil of Takeuchi Seiho, the Great Kanto Earthquake struck the Tokyo region. With its epicenter in northwestern Sagami Bay and an estimated magnitude of 7.9, it left over 100,000 dead or missing, and nearly 110,000 homes were completely destroyed by the tremors. The disaster was particularly devastating due to the widespread fires it caused, with approximately 210,000 buildings burned to the ground and around 90,000 of the 100,000 dead and missing reportedly resulting from the fires. In Japan, September 1, when the earthquake occurred, has been designated as the annual Disaster Prevention Day, and the week including this day is recognized as Disaster Prevention Week.

Twenty days after the earthquake, Yoson was invited by the Western-style painter Kanokogi Takeshiro to go the disaster-stricken area together with him. During his approximately one-month investigative visit, Yoson made around 400 sketches. Approximately 170 of these are in the collection of the Kurashiki City Art Museum, but in 1997 another 156 sketches were newly discovered and subsequently donated to this museum. In this special feature we are pleased to present all 156 of these sketches, although different works will be shown during the first and second terms due to their large number.

“I have never worked as hard as this, before or since.”

So said Yoson with regard to his painting After the Earthquake in 1923 (collection of the Kurashiki City Art Museum), which depicted the aftermath of the disaster based on the sketches he had made. Unfortunately it did not pass the screening for the 5th Teiten (Imperial Fine Arts Academy Exhibition) held the following year, but even today it eloquently conveys the massive devastation and tragedy of the earthquake. While working on this painting Yoson faced criticism and derision, and it was a lonely time in his life, but it was thanks to his diverse experiences including this one that he grew as an artist.

“Dear MoMAK”: Let’s Celebrate the 60th Anniversary of the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

This year, the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto (MoMAK) celebrates the 60th of its opening. What sorts of stories have emerged from relationships between visitors and the museum over the past six decades? Taking a look back at the history of MoMAK, we are currently asking people to share their memories of past exhibitions and events, as well as anecdotes related to memorable artworks and artists. Every day we have been receiving responses such as “I recall being overwhelmed by the power of the work,” “I felt close to the history [of the work] because it was made the same year that my grandfather was born,” or “I’ll never forget the dessert inspired by the art that I enjoyed at the museum restaurant.”

In a section of the permanent collection galleries, people’s written memories that connect to works and artists in our collection, selected by museum staff, are presented alongside the works themselves. We hope that as you enjoy your time at the museum, you will contemplate the many bonds that form between individual visitors and works of art.

“Dear MoMAK” welcomes everyone to participate, as many times as they like. On the occasion of our 60th anniversary, why not put down your own special memories on paper?

Exhibition Period

2023.07.13 thu. - 10.01 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

From Rekitei Art Association to Pan-Real and Pan-Real Art Association

Fragile: Restoration, Healing, Regeneration

Avant-Garde Textiles in the 1960s: Shimura Mitsuhiro, Nakano Mitsuo, Asada Shuji, Tajima Yukihiko

A Postwar Craft Association: Shinshokai

An 'Avant-garde' Era of Japanese Western-Style Painting

Special Feature: 100 years since the Great Kanto Earthquake

Ikeda Yoson’s Sketches of the Great Kanto Earthquake

“Dear MoMAK”: Let’s Celebrate the 60th Anniversary of the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

2nd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2023–2024 (266 works in all) (PDF)

2nd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2023–2024 (Special Feature) (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Hours

10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

*Fridays: 10:00 AM – 8:00 PM

*Admission until 30 min before closing.

*Opening hours is subject to change, due to the prevention against COVID-19 pandemic.

Please check the updated information, before your visit.

Admission

Adult: 430 yen (220 yen)

University students: 130 yen (70 yen)

High school students or younger,seniors (65 and over): Free

*Figures in parentheses are for groups of 20 or more.

Collection Gallery Free Admission Days

July 15, September 30, 2023

List of Works

2nd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2023–2024 (266 works in all) (PDF)

2nd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2023–2024 (Special Feature) (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)