Collection Gallery

5th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2021–2022

2022.01.20 thu. - 03.13 sun.

Winter Scenery in Japanese-style Painting, 2022 DOMOTO Insho, Winter Morning, 1932

This year is the Year of the Tiger. Among the teachings in the I Ching (The Book of Changes), one of the five classics of Confucianism is the following: “Clouds follow the dragon, the wind follows the tiger.” This proverb alludes to the idea that talented subordinates gather around outstanding monarchs, and many paintings of dragons and tigers are accompanied by depictions of the wind and clouds. Military commanders were fond of comparing themselves to a brave and daring tiger, leading artists to create numerous paintings of the animal. However, as tigers did not inhabit Japan, paintings such as Maruyama Okyo’s tigers with cat-like faces became well known in Kyoto. In the Meiji Period (1868-1912), works that were based on actual tigers began to appear, including Nishimura Goun’s Tiger, which depicts a tiger with realistic features rather than those of a cat.

During the New Year’s holidays in Japan, it was once common to see people flying kites or playing fukuwarai (a face-drawing game similar to pin the tail on the donkey) or sugoroku (board games), but today these activities seem to be things of the past. This is perhaps inevitable in light of the current situation in which many of us hesitate to take part in large gathers due to the coronavirus. Today, the best-known form of sugoroku is e-sugoroku (similar to snakes and ladders), which grew out of the two-person game of ban-sugoroku (similar to backgammon). As e-sugoroku can be played with a large group of people, it became a fixture of New Year’s gatherings since it allowed everyone to take part. Nakamura Daizaburo’s Study for Sugoroku (Japanese Board Game) shows two people playing ban-sugoroku, providing us with a view of the game, which is rarely seen today.

Snow fell in Kyoto from New Year’s Eve to New Year’s Day. Scenes of snow piled up on the ground typify winter for Japanese people, who cherish the four seasons. Painters have often depicted snowy scenery as part of various subjects related to Kyoto.

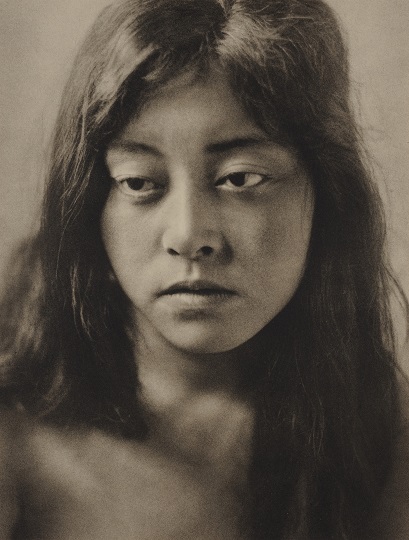

Artists and Their Models NOJIMA Yasuzo, Title unknown (Model F.), 1931

Kishida Ryusei’s friend and contemporary Nojima Yasuzo played a patron-like role, including holding Kishida’s solo exhibition at a salon in his home in Koishikawa-Takehayacho, Tokyo. Nojima’s photography was also greatly influenced by Kishida’s style. Transcending differences between the media of photography and painting, the works of Nojima and Kishida have much in common, such as dense and imposing still lifes made by closely observing subjects and conveying the power of their presence, and portraits that pursue clarity and realism.

Just as Kishida often had his beloved daughter Reiko model for paintings, many photographers directed their cameras toward close family and friends. While recuperating from injuries incurred while serving in World War II, W. Eugene Smith revived his activities as a photographer by documenting his children playing in the backyard. The Walk to Paradise Garden was, for Smith, “my first click of the shutter after the war,” and Smith may have pinned his hopes for the future on the cheerful expressions of his daughter Juanita who appears in the photographs. Other photographers who took a family-oriented approach include Harry Callahan, who achieved abstract visual beauty through the patient posing of his wife Eleanor, and Ralph Eugene Meatyard, who presented a unique worldview by having his family wear masks. Meanwhile, while there were photographers whose relationships with models always had romantic aspects – such as Edward Weston, Man Ray (whose model Kiki de Montparnasse was also popular among the painters of the École de Paris), Takehisa Yumeji, and Ikeda Masuo – the relationship between Nojima Yasuzo and the female “Model F” who frequently appears in his photographs remains shrouded in mystery. “Model F,” with her strong gaze directed back at the viewer, disheveled hair, and voluptuous body, presented a wild, indigenous-looking female image, which, like Kishida’s portraits of Reiko, is said to have gained popularity mainly among white-collar, intellectual urban male elites with an interest in the new art of the Taisho Era (1912-1926). However, the models in these works may not appear as their true selves, but in a sense be only muses or fabrications that reflect the ideals of the (usually male) photographer––in her Fairy Tales series, Yanagi Miwa takes aim at this one-way male gaze by presenting realities of the grotesque female figure.

Crafts of the Taisho Period YAMAMOTO Azumi, Cupronickel Flower Vase, "Lyricism of the Shinano Plateau", 1920

The Taisho Era (1912-1926) saw the emergence of the craftsperson as an individual creator, and marked a major turning point in how crafts were viewed. Here, “craftsperson” refers to a person who devises the concept for a work, chooses materials, selects appropriate techniques, and creates forms based on their own aesthetic sensibilities. Tomimoto Kenkichi, Bernard Leach, and Fujii Tatsukichi played pioneering roles in the development of this paradigm. Tomimoto was later designated as a Living National Treasure for mastery of the technique of overglaze enamels, Leach was an internationally acclaimed master known as the father of British studio pottery, and Fujii taught creative crafts in Seto and Obara, Aichi Prefecture while devoting himself to the popularization of handcrafting. However, what works of this period share in common is not pursuit of technical perfection or adherence to an established style, but rather a stance of imbuing works with one’s own view of life, even if not yet fully realized, and emphasizing sketching from life and forging a direct connection between nature and the self as a means of doing so. Botanical patterns frequently appear in the works of these three men, because they created original patterns by observing the natural world around them and making numerous sketches. The Taisho Era was already one in which naturalism greatly inspired young artists, as exemplified by the magazine Shirakaba, and in fact Leach and Tomimoto were also involved with Shirakaba. The development of creative crafts also influenced the lyrical work of artists such as Kusube Yaichi, Yamamoto Azumi, and Yamazaki Kakutaro, while by contrast the style of Katori Hotsuma was described as “neoclassicalism.” Katori is also known for research on the history of metalworking, and he gave his own metalwork a distinctly Japanese flavor by applying insights from this research to his own production. Meanwhile, Kiyomizu Rokubei V and Kawai Kanjiro applied the results of studies at the Kyoto City Ceramic Research Center in their own works, with Kiyomizu using colored porcelain made by mixing pigments directly into the clay substrate, and Kawai using copper red glazes that harness the volatile properties of copper.

KAWAI Kanjiro the Poet KAWAI Kanjiro, Rubbed Copies, c. 1950

While Kawai Kanjiro was primarily a ceramic artist, he also frequently took up the pen and produced a large amount of writing. This was not limited in subject to ceramics, but also dealt with childhood memories and a wide range of other topics, and the writing is highly appealing for its warm gaze and light-hearted narrative touch. Here, we present works primarily from the Kawakatsu Collection that showcase Kawai’s engagement with words.

Kawai’s literary activities can be traced back as far as the Gakuyu-kai circle in his junior high school years, and ranged from essays published in magazines such as Kogei (Crafts) and Mingei (Folk Crafts) to unpublished personal diaries and poetry. In 1916 he self-published a book titled Hi no kizo (Gift of Fire) collecting his short poetic writings, and these were later reworked and published after World War II as Inochi no mado (Window of Life) (Nishimura Shoten, 1948, reprinted by Toho Shobo in 1979), and were also produced as an illustrated book of rubbings. Kawai also conveyed ideas by coining four-kanji-character phrases embodying densely concentrated meaning, and inscribing them as works of calligraphy or on ceramic plates.

In “Togi shimatsu,” which was serialized in Kogei starting in 1931, the motif of hands that often appears in Kawai’s work appears as an illustration for the aphorism “One hand is a plate, two hands placed together become a bowl,” concisely expressing the evolution of human utensil-making as an extension of the body. When the artist deepened his philosophizing and arrived at the principle of “great harmony while in this world,” the motifs and rendering of enfolding hands placed together seem to have taken on a broader meaning.

Kawai’s writings convey a positive artistic attitude of accepting the ambiguities of things as they are. The artist, who transcended the distinction between self and others and considered his own words to be “the words of the reader,” wrote during his final years of the joy of living:

I want to meet myself as an unknown person, a stranger. Somewhere out there, there must be a new you and a new me. The world is growing smaller moment by moment. The distances between nations, the distance between human beings and the stars are shrinking, while in proportion to this our bodies and minds continue to expand. You and I have been invited into this great, endless land, by all the things of the world, we have been welcomed into this world as guests. How do we respond to this hospitality?*

*Kawai Kanjiro, “Zokei Kisuu (6): Kyouou Fujin (Rokujunenmae no ima [Sixty Years Ago] 53), Mingei no. 161 (May 1966).

KISHIDA Ryusei’s Friends and Enemies SEIMIYA Hitoshi, Still Life, 1918

Regarding the life of Kishida Ryusei, a champion of individualism in art during the Taisho Era (1912-1926), Umehara Ryuzaburo said that he “fought the good fight against many enemies,” but on the other hand, Kishida was also blessed with avid supporters and enthusiastic devotees.

Famous friends of Kishida’s include Mushanokoji Saneatsu, Nagayo Yoshiro, Shiga Naoya, Watsuji Tetsuro and Takamura Kotaro. The painter Seimiya Hitoshi had been a like-minded comrade since the days of the Fusain Society (fusain meaning “charcoal” in French), which Kishida formed early in his painting career, and Kimura Shohachi, Nakagawa Kazumasa, and Tsubaki Sadao later became devotees of Kishida’s and joined him in the artists’ group Sodosha, in which Kishida played a leading role. Sodosha later merged with a group of other painters after the abolition of the Yoga (Western-style painting) section of the Inten (Japan Art Institute Exhibition) and became Shunyo-kai, where Kishida continued to have enormous influence. Kishida was forced to leave Shunyo-kai due to the machinations of a faction led by Kosugi Hoan, who objected to this influence, but Umehara Ryuzaburo allied himself with the cast-out Kishida and left the group along with him. It can be said that in the painting world at the time, no one understood Kishida better than Umehara.

Ishii Hakutei was a painter who, like Umehara, had studied under Asai Chu, but in contrast, he became an opponent of Kishida’s. Also an art critic, Ishii evidently acknowledged Kishida’s talent, but it may have been impossible for Ishii, who believed that modern painters should paint modern subjects, to find common ground with Kishida, who pursued truth and beauty that transcended the times. The painter Ono Takanori was also an enemy of Kishida’s, but surprisingly, Ono and Ishii were both, like Kishida, painters who enjoyed the patronage of the prosperous businessman Shibakawa Terukichi.

Even more surprisingly, Kishida seems to harbored a dislike of Yorozu Tetsugoro, who had been active in the same circles since the early days of Kishida’s career. It seems relationships between brilliant people are often rocky.

Starting in October 1923, Kishida spent about two and a half years at Nanzenji Kusakawa-cho in Kyoto, and during this time he associated with Nihonga (Japanese-style) painters such as Kimura Shiko, Kajiwara Hisako, and Tsuchida Bakusen, as well as Yoga painters including Tsuda Seifu and Kuroda Jutaro. Kishida then moved to Kamakura, and when he made trips back to Kyoto, Okazaki Tokotsu (Yoshiro), who moved to Kyoto just as Kishida was departing, became a companion for nights on the town in the geisha district of Gion.

Western Art from the Time of KISHIDA Ryusei Piet MONDRIAN, Composition, 1929

In conjunction with the Commemorative Exhibition of New Acquisition: KISHIDA Riusei and the Morimura & Matsukata Collection, this section explores various aspects of art in the West during the lifetime of Kishida Ryusei.

Kishida’s career as a painter (1910–29) coincided with a time that, in Europe, included the World War I years (1914–18) and saw radical changes in art. Cubism, spearheaded by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, rejected traditional single-focus perspective and moved toward extreme dismantling, simplification, and abstraction of forms. Meanwhile, Fauvism, of which the most prominent practitioners included Henri Matisse, Andre Derain and Raoul Dufy, eschewed traditional realism and reproduction of colors as seen by the eye, emphasizing instead the power of colors themselves and color as an expression of the painter’s own sensibilities. Painters with non-French or non-Western European cultural backgrounds such as Amedeo Modigliani, Marc Chagall, and Fujita Tsuguharu, known as l’École de Paris, opened up new horizons by connecting their own artistic sources with Cubism, Fauvism and other avant-garde art movements. And in the work of artists such as Max Ernst, Piet Mondrian and Francis Picabia there was a focus on visual elements themselves, such as line, plane, and color, and the dynamism generated by their combination in works with abstract motifs or surrealistic subjects. Kishida’s lifetime overlapped with an era when fundamental questions about the nature of painting and art were explored in a wide variety of forms.

Here we are also pleased to present Prose on the Trans-Siberian Railway and of Little Jehanne of France (1913), a collaboration between the Ukrainian-born painter and designer Sonia Delaunay-Terk and the Swiss poet Blaise Cendrars, which the museum newly acquired this year. With vivid colors and series of rhythmic forms that generate lively images, intersecting with text that fluctuates due to use of multiple fonts and color applied between the lines, this work was described by its two creators as a “simultaneous book.” A hybrid of painting and literature, it is one of the most significant artists’ books of the 20th century.

Exhibition Period

2022.01.20 thu. - 03.13 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Winter Scenery in Japanese-style Painting, 2022

Artists and Their Models

Crafts of the Taisho Period

KAWAI Kanjiro the Poet

KISHIDA Ryusei’s Friends and Enemies

Western Art from the Time of KISHIDA Ryusei

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

5th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2021–2022 (168 works in all) (PDF 334KB)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Hours

9:30AM–5:00PM

*Fridays and Saturdays: 9:30AM–8:00PM

*Admission until 30 min. before closing

*Opening hours is subject to change, due to the prevention against COVID-19 pandemic. Please check the updated information, before your visit.

Admission

Adult: 430 yen (220 yen)

University students: 130 yen (70 yen)

High school students or younger,seniors (65 and over): Free

*Figures in parentheses are for groups of 20 or more.

Collection Gallery Free Admission Days

January 22, March 12, 2022

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)