_02_2336.jpg)

Collection Gallery

2nd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2018–2019

2018.05.30 wed. - 07.29 sun.

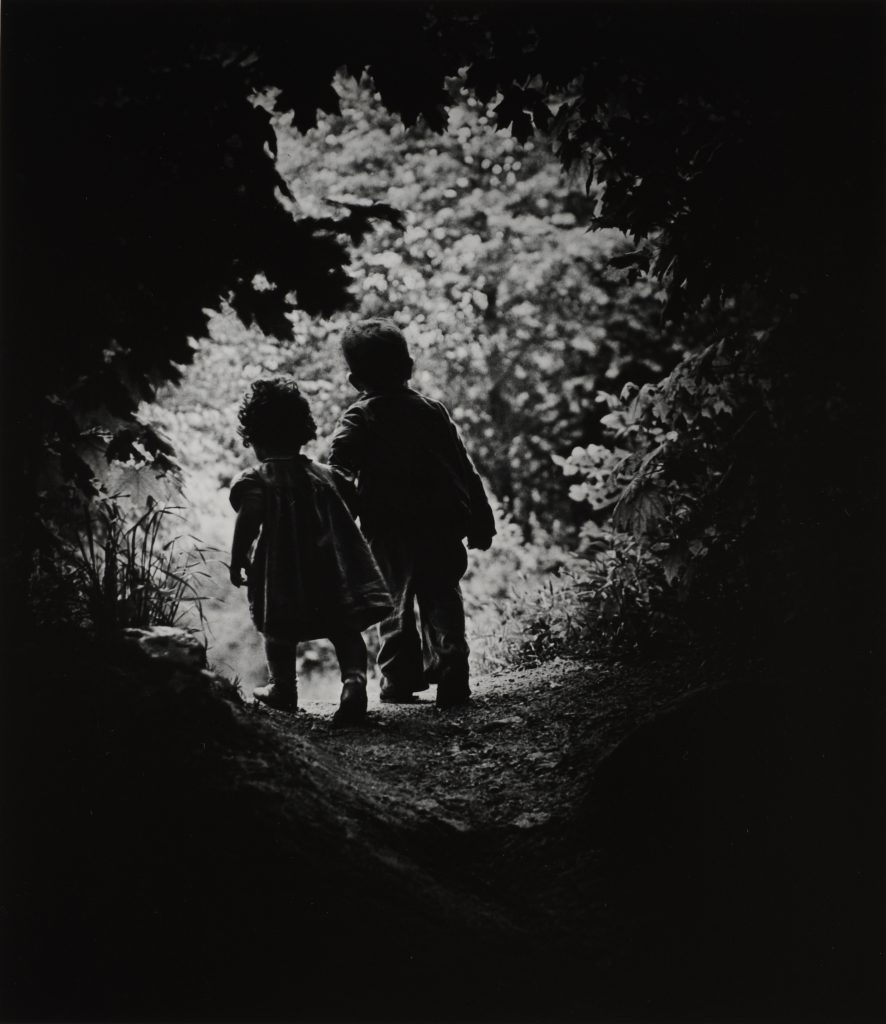

Photographs by W. Eugene SMITH W. Eugene SMITH The Walk to Paradise Garden, 1946 © 1946, 2018 The Heirs of W. Eugene Smith

W. Eugene Smith (1918–1978) was a photojournalist who published many photo essays in the photography-oriented American news magazine Life and elsewhere, and whose subjects included Minamata disease, which he traveled to Japan to document. Smith was born in Wichita, Kansas, USA in 1918, and moved to New York in 1937 at the age of 18 to become a professional photographer. During World War II he was a war correspondent for Life, documenting battle zones on the front lines such as Saipan, Iwo Jima and Okinawa in photographs that were published in the magazine. Smith's witnessing the misery of civilians swept up in the war at this time had a powerful influence on his ethical views as a photographer.

After returning to the United States following the war, he published photo essays in Life such as "Country Doctor" and "Spanish Village." With iconic photographs that pursued truth while taking a fundamentally subjective approach, light-and-dark contrasts, masterful incorporation of compositions from classical paintings, and underlying humanism rooted in a belief in the American spirit of justice at its finest, Smith had a major impact on the development of photojournalism.

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto has been acquiring Smith's photographs on an ongoing basis since 1995. These photographs were carefully selected and saved by Aileen Mioko Smith, his partner on the Minamata project. This year, 100 years after his birth and 40 since his death, we will exhibit 90 works selected from the Aileen Smith Collection, as a retrospective spanning almost the entire length of W. Eugene Smith's photographic career.

Animals in Modern Painting ISHIGAKI, Eitaro, Whipping, 1925

Animals have been a favorite subject in art throughout history and around the world. No doubt this is because among the birds, beasts, bugs and fish around us are many creatures that are familiar and even indispensable for human life. Some animals provide us with food, others help with aspects of daily life, and others are treated as beloved family members. Thus it may seem only natural for animals to appear frequently in art, but there are other reasons as well. Animals have also symbolized all manner of concepts and ideals in the history and culture of various regions of the world. For example, in parts of East Asia bats symbolize happiness, and schools of fish represent fertility and perpetuation of one's lineage. Such symbolic images of animals have brought joy to viewers everywhere.

Animals have also been a popular subject in Japanese modern art, but in Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) expression of the beauty and symbolic meanings of animals often carried on aspects of East Asian tradition, while in Yoga (Western-style painting), under the banner of modernity, they were often explored in purely visual terms. We could say that for this reason, the latter often shows us the artists' direct and unadulterated views of animals.

This area showcases works depicting animals from among the modern Japanese Western-style paintings in the museum's collection. Some feature animals as the main subjects, others highlight animals as part of the landscape and human customs. As you view this area, you may enjoy imagining how the artists saw the animals as they worked on the paintings.

Picasso and Matisse and others Henri Matisse, Small Blue Dress before a Mirror, 1937

Here we present work by two of the masters of 20th century art, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Matisse, born in France in 1869, joined Maurice de Vlaminck, Raoul Dufy and others as a leading figure among the Fauves (literally "wild beasts," so-called for their raucous use of color). Picasso, born in Spain in 1881, founded the Cubist movement with Georges Braque. Picasso and Matisse first met around 1906 through the brother and sister Leo and Gertrude Stein, who collected work by both of them. While their artistic styles, personalities, and ideas about painting differed, the two drew inspiration from one another, and over a lifetime of mutual respect as well as rivalry, explored expanses of uncharted territory in 20th-century painting.

Henri Matisse's Small Blue Dress Before a Mirror was in the collection of the Paris art dealer Paul Rosenberg, but then entered the possession of Hermann Göring, who addition to being second only to Hitler in the Nazi regime, was also an art collector. When World War II began, the Nazis systematically plundered artworks in France as elsewhere, including works kept by Rosenberg, who was Jewish. Fortunately, this work was undamaged in the fighting, returned to Rosenberg after the war, and was acquired by this museum in 1978. Picasso's Still Life: Palette, Candlestick and Head of Minotaur was painted the year after Guernica, his masterpiece inspired by the Germans' indiscriminate bombing of a Spanish village, and the two paintings share motifs including a candlestick and a Minotaur's head.

What qualifies Matisse and Picasso as masters? One could cite their vigorous dedication to their art over many years, and the fact that both left behind such vast bodies of work, thanks in part to their widespread popularity during their lifetimes. The fact that the vast majority of works by these two artists, who both lived through two world wars in Europe, survive to this day reflects countless people's dedication to ensuring these works were not destroyed by war or disaster.

Yokoyama Taikan and Artists of the Japan Art Institute (Nihon Bijutsuin) HAYAMI, Gyoshu, Scenes from Egypt,1931

This exhibit is related to the retrospective The 150th Anniversary of his Birth: Yokoyama Taikan on view in the third-floor special exhibition gallery.

Yokoyama Taikan enrolled as a member of the first graduating class at Tokyo School of Fine Arts (the predecessor of Tokyo University of the Arts) in 1889, and in 1896 became an assistant professor there, but in 1898 he resigned in sympathy with Okakura Tenshin, his mentor and the head of the school, who was forced to leave for political affairs in the school, and joined him in forming the Japan Fine Arts Academy (Nihon Bijutsuin). Taikan, Hishida Shunso, and others sought to realize Tenshin's vision with the Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) technique of mossen (lit. "sunken lines," i.e. blurring of contours), using karabake (deer hair brushes). This dramatically different style without clear outlines was derided as moro-tai ("blurry style"), and its critical rejection was a factor in the decline of Nihon Bijutsuin, which forced the Nihonga section of the Academy to move to Tenshin's villa in Izura, Ibaraki Prefecture. However, Taikan took these difficulties in stride, submitting ambitious work to the Bunten (Ministry of Education Fine Arts Exhibition) in 1907 and succeeding in the mainstream painting world. He became a Bunten judge but was later removed from his post by conservative forces, and in 1914 carried on the philosophy of Tenshin, who had died the previous year, by cutting ties with the official painting world and reviving Nihon Bijutsuin with his associate Shimomura Kanzan. Among the active members of the revived Academy were Yasuda Yukihiko, Maeda Seison, and Kobayashi Kokei, nicknamed the "three ravens," and painters one generation younger such as Hayami Gyoshu, and despite being an independent and unaffiliated association, it rivaled the official Kanten exhibitions in influence, and exists to this day.

This area features works by Yokoyama Taikan, Hishida Shunso, and the above-mentioned members of the revived Nihon Bijutsuin, as well as Taikan's protégé Katayama Nampu; Tomita Keisen and Komatsu Hitoshi, among the few Bijutsuin members active in Kyoto; and Ogura Yuki, who led the Academy after the death of the "three ravens."

Selected Works by KAWAI Kanjiro KAWAI, Kanjiro, Bowl of Fish Design, 1951

Kawai Kanjiro, one of the greatest ceramicists of modern Japan, was born in 1890 in what is today Yasugi, Shimane Prefecture. After graduating from Tokyo Higher Polytechnical School (present-day Tokyo Institute of Technology), he taught at Kyoto City Ceramic Research Institute, devoting himself to research and development of tens of thousands of glazes. After resigning from the Institute in 1917 and becoming an independent ceramic artist, he held his first solo exhibition of Chinese-influenced ceramics in 1921, a spectacular debut that earned critical praise like "genius appears suddenly like a comet." After this, however, Kawai dramatically shifted direction and participated in the Mingei (folk art) movement, creating ceramics closely linked to daily living and the act of creation. Kawai's work became ever more formally ambitious in his later years, overflowing with the joy of life.

The Kawakatsu Collection, assembled by Kawai's longtime patron Kawakatsu Kenichi, forms the core of the museum's collection of works by Kawai. As the greatest public collection of Kawai's work in terms of both quantity and quality, winning the Grand Prize at the Paris Exposition in 1937, the Kawakatsu Collection contains important works from all stages of Kawai's career, and is indispensable in tracing the evolution of his creative vision. In addition to the Kawakatsu Collection, other Kawai works have been donated to the museum over the years.

This exhibition showcases the varied works of Kawai Kanjiro, including many from outside the Kawakatsu Collection that have rarely been shown before.

Works of Japanese Modern Crafts NOBUTA, Yo, Kettle for Evaporation, 1934

Japanese crafts were exported in large volumes during the first half of the Meiji Era (1868-1912), and in the latter Meiji Era began to show more creativity and diversity, with outstanding designs and development of individual artists' distinctive vision. A fine example can be seen in the simplified, planar gold lacquer and mother-of-pearl inlay works of Kamisaka Yukichi, a departure from traditional depictions of the beauties of nature in these media. Tomimoto Kenkichi explored a singular creative world in patterns based on sketches from nature and the pursuit of integration of pottery form and patterns. Kitaoji Rosanjin applied his protean talent to diverse media including calligraphy, seal carving, cooking, ceramics, lacquerware and painting, and shown here is one of Rosanjin's finest works in white porcelain decorated with calligraphy in the kago-ji style.

A significant turning point for Japanese crafts came in 1927, when a category "Craft as Art" was added to the existing categories of the Teiten (Imperial Art Exhibition). When crafts gained official recognition as an art form, many artisans began creating works that reflected the artistic trends of the day. Works by Kusube Yaichi, Kiyomizu Rokubei VI, Nobuta You, and Kagami Kozo, who were inspired by the Art Deco style, vividly convey the flavor of creative crafts from the early Showa Era (1926-1989). In the context of crafts as a creative art, after World War II the contrasting concept of "traditional crafts" gained currency, and much attention was paid to the artistic and historical richness of skills and techniques learned over many years (known as Important Intangible Cultural Assets). Shown here are textile works by four Living National Treasures (i.e. masters of these intangible skills and techniques), including Serizawa Keisuke.

Meanwhile, as members of the avant-garde ceramics group Sodeisha, Yagi Kazuo and Suzuki Osamu pioneered ceramics as a form of sculpture. Their early works present a picture of the way both classical ceramics and contemporary art were contextualized during the modern era.

Exhibition Period

2018.05.30 wed. - 07.29 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Photographs by W. Eugene SMITH

Animals in Modern Painting

Picasso and Matisse and others

Yokoyama Taikan and Artists of the Japan Art Institute (Nihon Bijutsuin)

Selected Works by KAWAI Kanjiro

Works of Japanese Modern Crafts

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

2nd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2018–2019 (201 works)(PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

_02-1.jpg)