Collection Gallery5th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2017–2018 (121 works in all)

Collection Gallery

HOME > Collection Gallery > 5th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2017–2018

5th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2017–2018 (121 works in all)

Exhibition Period

1. 5 (Fri.) – 3. 11 (Sun.), 2018

Themes of Exhibition

- ・Curatorial Studies 12: The 100th Anniversary of Duchamp's Fountain

Case 5: Dissémination, curated by MOHRI Yuko - ・January 20, 1918: Birth of the Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai

- ・The Dawn of Creative Crafts

- ・Kawai Kanjiro, Poet

- ・The Fauves

- ・HATAKEYAMA Naoya "Atmos"

- ・"Playroom" (1F Lobby)

- ・[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

Curatorial Studies 12: The 100th Anniversary of Duchamp's Fountain

Case 5: Dissémination, curated by MOHRI Yuko

Duchamp was working on his readymades at the same time as The Large Glass. This exhibit focuses on whether or not there is some connection between the two.

Some hints are contained within the works themselves. Next to a miniature (!) of The Large Glass, the main component in Duchamp’s portable work Boîte-en-valise (Box in a Suitcase), there are miniatures of three readymades arranged from top to bottom as follows: 50cc of Paris Air, Traveler's Folding Item, and Fountain. According to one theory, these were intended to correspond to the three parts of The Large Glass: the bride section at the top, the border between the upper and lower parts (a wedding dress or clothing – something that can both taken off prior to "the act" and put on after "the business" over? LOL), and the bachelor section at the bottom. In a large-scale retrospective held at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1963, the curator, Walter Hopps, made a cute display with the three readymades arranged vertically as a reference to Boîte-en-valise.

It is widely known that Duchamp hung the readymades around his studio. And some have suggested that he did this to understand the relationship between two and three dimensions – i.e., the relationship between the shadows of the hanging objects and the walls and ceiling on which they were projected. In other words, the shadows were two-dimensional projections of three-dimensional objects. Plato's "Allegory of the Cave" is an idealistic anecdote, and Duchamp came up with the idea that the three-dimensional world we live in is actually a projection of the fourth dimension.

In graduate school, whenever I had time on my hands, I would wander around and eventually end at some kind of museum. I'll never forget what a mind-blowing experience it was to encounter Model of Seismic Vibration Traces on one of those trips. The model, based on an earthquake that occurred on January 15, 1887, used bent wire to show how a certain point on the ground changed according to the vibrations at any given time – in other words, it was a projection of the fourth-dimensional world (time) on the third-dimensional world. Since the device was made in the late 19th century, it was made by hand instead of with a precision measuring instrument or a computer, and the amount of information it contained was truly stunning. The rough handmade quality also gave it a humorous appearance.

Another thing I saw on a graduate school-era walk was a Perspective Entity Model. This complicated contraption was a three-dimensional model of a three-dimensional spatial concept expressed in the two dimensions. There was also something funny about the deadly serious air of the device. This is slightly off topic, but the artist Takamatsu Jiro was also attracted to this sort of thing, as seen in a work like Chairs and the Table in Perspective.

Since the majority of Duchamp's unpublished notes in A l'infinitif (The White Box) have to do with the fourth dimension and perspective, I thought these devices would be appropriate for this exhibit.

This might sound presumptuous, but based on my intuition as someone in the same line of work as Duchamp, it is hard to imagine that there isn't some sort of connection between the readymades and The Large Glass. Isn't that what he's hinting at in Boîte-en-valise? Assuming that this is the case, I decided to copy Boîte-en-valis and the Pasadena show, and shove (this reproduction of) Duchamp's legendary work Fountain, which has been subjected to all sorts of things (LOL) during this series celebrating its 100th anniversary, up against The Large Glass.

My methodology was the exact opposite of Duchamp's. I turned The Large Glass, by definition a two-dimensional work, into something three-dimensional, enabling the viewer to walk around it as they look at the piece. In other words, you the viewer are already inside The Large Glass. The awareness or experience of walking around the work, which has a certain degree of thickness (or in this case, height), might be seen in contemporary terms as akin to the relationship between a planar map and a global navigation system (discussing this concept with Kozuma Sekai proved to be very helpful). If you can forgive me for focusing on the unpleasant nature of the subject matter, the framework makes for a truly splendid Large Glass. Alongside it, I have arranged the readymades in tribute to Pasadena, making the space a virtual reproduction of Boîte-en-valise.

This thick two-dimensional object (=three dimensional) functions as a projection of the fourth dimension. Doesn't this make the relationship between the third and the fourth dimensions somehow plausible?

The exhibit also encompasses some gender-related elements, but since I have already gone way over my word limit here, I will leave you to your own devices. Unlike the readymades and The Large Glass, there is a deep dark river between men and women. One thing you can say for sure is that even though all of us artists are Duchamp's (unfertilized) children, regardless of a few queer elements, the boyish artist doesn't seem to have had any eggs.

Mohri Yuko (Artist)

January 20, 1918: Birth of the Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai

“Art is what is born, not what is achieved by an art association. This truth lurks behind the most brilliant accomplishments, and man's recognition of this truth underlies the blossoming of the senses and flows throughout the changing seasons of life. Indeed, it is only when an artist deepens himself and manages to produce a consistent body of work that he becomes able to see his own growth. Based on this belief, we see potential comrades in all living things. We hereby establish the Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai [Society for Creation of a National Painting Style], and we will create various venues and opportunities for our comrades to exhibit their works. Our heartfelt desire is to contribute to the development of Japanese painting.”

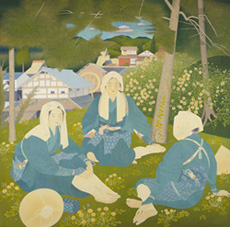

On January 20, 1918 at the Kyoto Hotel, the Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai was established, its founding members being Tsuchida Bakusen, Ono Chikkyo, Murakami Kagaku, Sakakibara Shiho, and Nonagase Banka (Irie Hako also contributed greatly to the group’s establishment, but felt that his own skill was not sufficient and bowed out of being a founding member. However, he joined after winning the Kokuten Award at the group’s first exhibition.) The Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai Declaration, which begins with the passage above, calls for respect for individuality, freedom of creation, and love for nature. It powerfully inspired many young painters, and there were numerous submissions to the first exhibition held in November of that year, not only from Kyoto, but from all over Japan. The exhibition brought together works reflecting various trends, including enchanting female figures, drawings influenced by Northern Renaissance art, and detailed renderings in a Western style, and developed into a gathering place for emerging painters that the official Bunten (Ministry of Education Art Exhibition) did not accept. For financial reasons, the group was unfortunately dissolved after the 7th exhibition in 1928 (former Kokuga members and affiliates went on to form the Shinjusha group, but it petered out after holding two exhibitions), but over its 10 years of existence, it gave rise to unique and richly original works that invigorated Japanese painting during the Taisho Era (1912–1926), when modern Japan was in its youth, with originality and energy that we can still feel vividly today.

By presenting works first shown at the Kokuga Sogaku Kyokai exhibition, or produced by its members during the same era, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the group’s formation, we hope to shine a fresh spotlight on this seminal group’s activities.

- TSUCHIDA, Bakusen Oharame (Woman Peddlers from Ohara), 1927

The Dawn of Creative Crafts

From the late Meiji Era (1868–1912) onward, Asai Chu, Kamisaka Sekka and their associates engaged in design research and crafts production in cooperation with Kyoto artisans, organizing the Yutoen ceramics and Kyoshitsuen lacquerwork groups. In doing so, they drew inspiration from the Rimpa school and found new value in the decorative qualities of crafts.

The Living National Treasure bronze artist Takamura Toyochika also cites Tomimoto Kenkichi, Fujii Tatsukichi, and Tsuda Seifu as essential figures in the history of modern Japanese crafts, as well as Bernard Leach, Arai Kinya, and Kawai Unosuke, artists deserving mention who exerted an enormous influence on the Japanese art world during this era. Takamura says that these artists are so important because they showed new ways of viewing the world. They did so by closely observing nature, exploring the spirit according to the creator's desires, and producing crafts as a manifestation of creative freedom, as opposed to traditional crafts' emphasis on technical skill, established styles, and perfect finish. During this period, many artists produced crafts that transcended traditional areas of expertise, in the belief that works of craft, as a part of day-to-day “living,” are a means of directly expressing “life.”

Works from this period sometimes have a strongly handmade and even naïve quality. This was a deliberate approach, intended to reflect the spiritual more directly rather than diluting it with technical perfection. This later led to further creative work in the crafts field, such as that of Kusube Yaichi’s Sekido-sha (lit. “Red Clay Group”).

- FUJII, Tatsukichi Folding Screen with Palm Design, c.1916

Kawai Kanjiro, Poet

The works by Kawai Kanjiro in this museum’s possession are largely from the collection of Kawakatsu Kenichi, a supporter of Kawai’s for many years. This body of work encompasses Kawai’s best-known pieces from all stages of his career, and is indispensable in tracing the evolution of his creative ambitions.

Kawai, a preeminent figure in modern Japanese ceramics, was born in what is now Yasugi, Shimane Prefecture in 1890. After graduating from Tokyo Higher Polytechnical School (now Tokyo Institute of Technology), Kawai began working as a teacher at the Kyoto Municipal Ceramic Laboratory. Kawai left the laboratory in 1917 and set out to be a ceramic artist, making a stunning debut in 1921 with his first solo exhibition of works inspired by Chinese ceramics, hailed as “the sudden appearance of a genius, like a comet in the heavens.” However, he went on to shift directions dramatically and became a key figure in the Mingei (folk art) movement, his production of pottery inextricably linked to everyday life. His works became ever more artistically ambitious in his later years, overflowing with the joy of life and being.

During World War II, when it was difficult to pursue art freely, Kawai devoted himself to poetry, and in 1947 self-published Inochi no mado (Window of Life), expressing beliefs that he continued to explore after the war in a wide range of media. In this exhibition, we explore one side of this multifaceted artist, focusing primarily on his poetry.

- KAWAI, Kanjiro Plate, c.1949

The Fauves

In the late 19th century, Van Gogh pioneered a style expressing the artist’s subjective perceptions through intense colors and unrestrained brushstrokes. In the 20th century, the painting movement known as Fauvism carried on this approach, with Henri Matisse and Maurice de Vlaminck among its best-known adherents.

The term Fauvism appropriated a critic’s disparaging description of the painters as "like wild beasts (fauves) in cages." The revolutionary Parisian movement had a great influence on young painters, and international students from Japan were no exception.

In Japan, the work of Van Gogh was known through reproductions that began to be published in the 1910s, and fascinated a young generation that began to awaken to individuality against the backdrop of the Taisho Democracy then unfolding. In this context, Nakagawa Kigen went to Europe in 1919 and studied under Matisse, while Satomi Katsuzo traveled there in 1921 and studied under Vlaminck, both directly encountering Fauvism in Paris. After returning to Japan, they became evangelists for the new style, disrupting the world of yoga (Western-style painting).

Satomi in particular famously introduced Saeki Yuzo to Vlaminck while in France, shaping the direction of Saeki’s work thereafter. After returning to Japan, Satomi joined Saeki, Maeda Kanji and others in forming the strongly Fauvism-tinged 1930-nen Kyokai (1930 Society), which in 1930 developed into the Dokuritsu Bijutsu Kyokai (Independent Art Society) and played an important role in cementing Fauvist influence on Western-style painting in Japan before World War II.

This area features works by Japanese Fauvist painters, with a focus on Nakagawa Kigen and Satomi Katsuzo.