Collection Gallery

3rd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2019–2020

2019.06.12 wed. - 08.04 sun.

Murakami Kagaku: 80th anniversary of his death Murakami Kagaku, Avalokiteśvara, The Sacred Lotus, 1930

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto has often focused on the work of Murakami Kagaku, featuring him as the first modern Nihonga painter, and holding a major retrospective in 2005. This year, 80 years have passed since the artist's death in November 1939, and we are pleased to mark it with a special commemorative exhibition.

After graduating from the Kyoto City School of Arts and Crafts, Murakami enrolled in 1909 at the newly established Kyoto City Art College (present-day Kyoto City University of Arts). At both institutions he studied the Maruyama Shijo School of painting, incorporated elements of ukiyo-e, Nanga or Southern School (Japanese painting inspired by Chinese literati painting), and Western painting, and frequently exhibited and won prizes at the Bunten Exhibition organized by the Ministry of Education. However, he and the artists Irie Hako, Sakakibara Shiho, Tsuchida Bakusen, Ono Chikkyo, and Nonagase Banka, whom he had gotten to know at the two schools, became dissatisfied with the criteria employed by the Bunten, the only place they were able to exhibit, and in 1918 they formed the Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai (Society for the Creation of a National Painting Style), seeking opportunities to create and exhibit work freely and establishing their own series of exhibitions known as the Kokuten.

However, Murakami had always harbored the idea that the art-world establishment itself constrained artists' freedom and rendered their activities impure, and he was also suffering from worsening chronic asthma. For these reasons, after exhibiting in the 5th Kokuten in 1926, he withdrew from the art scene and the following year moved to Hanakuma, Kobe where his family home was located. There, while living the life of a recluse, he continued producing art in a manner similar to religious training, having come to believe, as embodied by his famous quote "Art is prayer behind closed doors," that painting was a means of grasping the essence of the world and understanding the ultimate truths of the cosmos. His primary subjects – Buddhist imagery, Mt. Rokko, peonies and camellia – were mainly rendered in sumi ink, but the paintings were not completely monochromatic. They may appear at first to be executed in ink alone, but take time and look at them from different angles, and in areas that appear to be blank paper, there is actually chalk-white pigment, or subtle shades of turquoise, vermilion, burnt sienna or yellow ocher, or touches of gold, silver, and aluminum paint applied, understated accents that delight the eye and the heart.

This special exhibition features, in addition to 20 works from the collection and about 50 entrusted to the museum, various materials related to Murakami, as well as the master sketches for a major work by his close associate Irie Hako, which were recently restored. The first term of the exhibition (April 26–June 9) will focus on works from the Kyoto City Art College through the Kokuten era, and the second half (June 12–August 4) primarily on works from his years of seclusion in Hanakuma. This two-part exhibition will enable viewers to immerse themselves fully in the marvelous world of Murakami's art.

Botanical Garden: From Plant Drawings to Kudo Tetsumi KUDO, Tetsumi, Portrait of Ionesco , 1970-71

"He studies a single blade of grass."

This quote is from Vincent van Gogh, who was profoundly impressed by an Edo Period (1603-1868) Japanese painter's depictions of plants. Plants are a familiar subject to which artists have turned again and again, producing an immense variety of works. In the colorful rendering in the collection Western Herbs and Flowers by the Nihonga (modern Japanese-style) painter Chigusa Soun, we can see the curiosity and enthusiasm of an artist keen to observe and study the rare flowers then being imported from the West. In his portfolio of prints Natural History (Histoire naturelle), Max Ernst transferred the patterns of leaf veins, wood grain, threads, wire nets and so forth with the technique of frottage, transforming abstract forms into images of natural phenomena and botanical and biological motifs. While taking a walk, the printmaker Hasegawa Kiyoshi once felt that an old tree was greeting him, saying "Bonjour!" and this experience led him to develop a unique view of nature in which divinity pervades the most ordinary scenery and humble flowers.

A very different view of nature can be seen in Kudo Tetsumi's plastic artificial flowers, which ironically convey relationships between plants (and nature in general) and humans in modern society. Active in Europe beginning in the 1960s, Kudo consistently critiqued humanity's technological advancement and civilized society, which pollute the environment and are underpinned by an anthropocentric view of the world. The work of Lothar Baumgarten also deals with relationships between nature and humanity (or the artificial), adopting an ethnographic approach, and pointing out that the systematized mindset of the museum and the very concepts of "nature" and "culture" are products of human thought. Looking back on their work now, these artists seem to have keenly foreseen the tribulations of the coming Anthropocene (the geological period in which human activity has come to affect the global environment drastically.)

Glass Works of the World

Glass has been produced since ancient times in many parts of the world, including Rome and Egypt, and its transparency and vivid colors have enchanted people throughout the ages. While in the modern era glass is manufactured as an industrial product, the studio glass movement, which began in the 1950s with freewheeling, highly original practices in the Czech Republic and the United States, has gained increasing popularity over the years. Here we can see relevance to the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement, such as a return to work by hand, respect for individuality, and reaction against the alienation of advanced industrialized society. Over a relatively short span of time, the range of works produced with glass has expanded dramatically.

A primary feature of glass work, like other types of crafts, is the manifestation of specific material properties. These properties of transparency, brilliance, and versatility of color are rendered visible with a variety of shaping techniques such as cutting, polishing and engraving. Artists have looked at the world around them in terms of these properties, and used glass to express various aspects of contemporary society.

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto held the glass-themed exhibitions Contemporary Glass: Europe & Japan and Contemporary Glass: Australia, Canada, USA & Japan in 1980 and 1981 respectively. Works from these exhibitions form the core of the museum's collection of glass works, but since then we have continuously worked to enhance the collection through exhibitions introducing contemporary crafts from around the world. Here, we have carefully selected 15 pieces from the collection to present glass works from around the world to viewers in a distinctive light.

Selected Works of KAWAI Kanjiro from the KAWAKATSU Collection KAWAI Kanjiro, Slip Inlayed Bowl, 1922

The Kawakatsu Collection, which includes a grand-prize winning piece from the 1937 Paris International Exposition, constitutes the most substantial public collection of Kawai Kanjiro's works in terms of both quality and quantity.

The collection was donated to the museum by the businessman Kawakatsu Kenichi in 1968. When a museum curator went to see Kawakatsu's huge collection of Kawai's works, which placed an entire space of his house, he said, "Choose as many as you like." In the end, 415 items were selected. Along with three pieces that Kawakatsu had previously donated to the museum and seven others that were subsequently added to address a lack of Kawai's early works, the collection eventually totaled 425 works. Made up of important works by the artist, stretching from his first efforts, which were modeled on Chinese porcelain, to his final pieces, made after his involvement with the Mingei movement, the collection is truly a chronological encyclopedia of Kawai's ceramics that spans his entire career.

Kawakatsu (1892–1979), who assembled the collection, worked as the advertising manager at the Tokyo branch of Takashimaya Department Store as well as serving as the store's general manager, and the senior managing director of the Yokohama branch. In his role as a member of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry's craft examination committee, he also strove to foster craft designs.

Kawai's long friendship with Kawakatsu began when he went to meet the artist at the station when Kawai traveled to Tokyo for a meeting regarding the 1st Creative Ceramics Exhibition, which was held at Takashimaya in 1921. Immediately sensing that they were kindred spirits, Kawakatsu began collecting Kawai's works. Reminiscing about the collection, Kawakatsu said, "It wasn't merely based on my personal taste. Sometimes Kawai would make works for the collection and he also chose lots of pieces for it." He added, "It was the crystallization of our friendship."

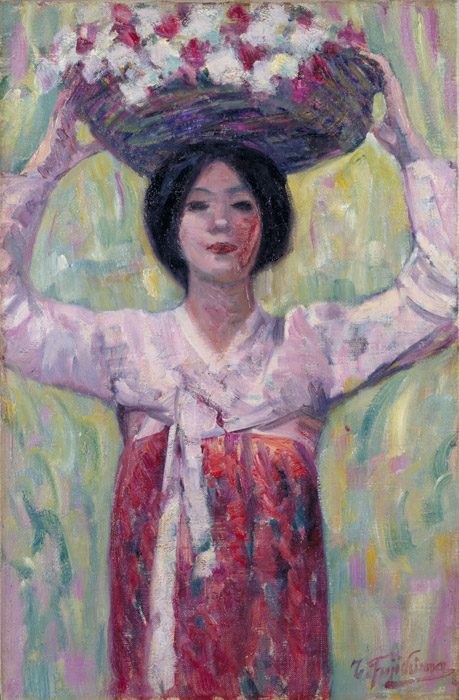

Flowers in Japanese Western-Style Painting FUJISHIMA Takeji, Flower Basket, 1913

The special exhibition The Treasures and the Traditon of "Lâle" in the Ottoman Empire, held this year, presented many artworks of the Ottoman era featuring tulip patterns. In art of much of the Islamic world, roses and similar flowers were the preferred motifs for botanical patterns, but the tulip was particularly beloved in the Ottoman Empire. Tulips were thought to symbolize Allah, as well as to represent the Ottoman ancestors.

Plants have been a favored subject not only in the Ottoman Empire, but in every region of the world. In every nation and era of history, loving the beauty of flowers and entrusting them with our wishes and prayers has been a universal human practice. In Japan, as well, since ancient times people have created diverse works of art and decorated various spaces with floral and botanical motifs and patterns. Influenced by Chinese tradition, in which various plants allegorically represent happiness and prosperity, many sorts of plants have been viewed as "auspicious" in Japan. Flowers also gave visual form to memory in waka and haiku poetry and stories

which describe the emotions flowers evoke, and took on rich significance.

In the latter half of the Edo Period (1603-1868), Western art and natural sciences came to be an influence, and precise depicitions of plant and animal morphology gained popularity. Since the Meiji Era (1868-1912), when appreciation and adoption of Western painting began in earnest, flowers came to be rendered in purely visual terms in still life and landscape oil paintings. Still, when some flowers such as plum blossoms, cherry blossoms, morning glories, and chrysanthemums appear, memories of the flower and bird paintings and classical literature of an earlier era seem to persist.

Here we are pleased to present a wide range of works featuring flowers from the museum's collection of modern Japanese Western-style painting.

Exhibition Period

2019.06.12 wed. - 08.04 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Murakami Kagaku: 80th anniversary of his death

Botanical Garden: From Plant Drawings to Kudo Tetsumi

Glass Works of the World

Selected Works of KAWAI Kanjiro from the KAWAKATSU Collection

Flowers in Japanese Western-Style Painting

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

3rd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2019–2020 (138 works)(PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

_1930.jpg)