Collection Gallery

4th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2018–2019

2018.10.16 tue. - 12.16 sun.

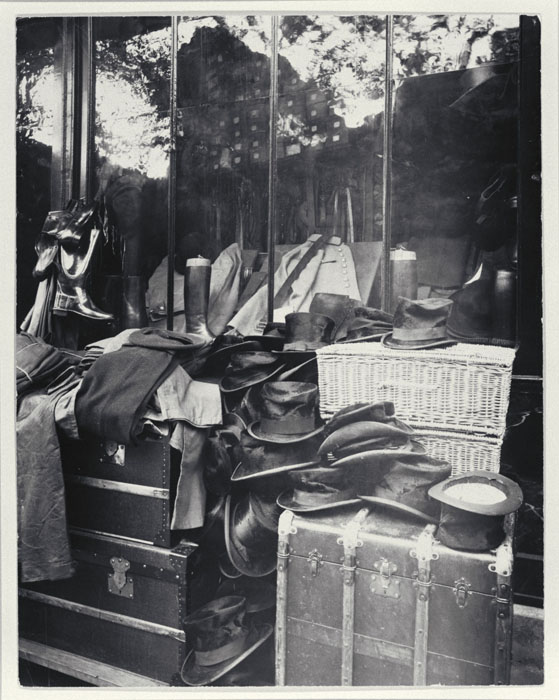

Paris as Artistic Community Jean-Eugene-Auguste ATGET, Boutique #91, 1910

In the Woody Allen movie Midnight in Paris, the main character Gil, a present-day American, travels back in time to Paris in the 1920s and encounters creative figures he admires such as Hemingway, Cocteau, Picasso, Dali, and Man Ray. In Paris during this era, known as the Belle Époque or the Roaring 20s, Foujita Tsuguharu was also a presence, drawing attention with the unique style of painting he developed.

The Paris to which Foujita relocated as a young aspiring painter had since the late 19th century given rise to one groundbreaking art movement after another – Impressionism, Symbolism, Fauvism, Cubism – and young artists flocked there from all over the world. Foreign artists who worked in and around shared studios such as Le Bateau-Lavoir ("the boat wash-house") in Montmartre and La Ruche ("the beehive") in Montparnasse from the 1900s to the 1920s, such as Foujita (Japan), Modigliani (Italy), Kisling (Poland), and Chagall (from Russia) were at the time known collectively as l'École de Paris (the School of Paris). This term conveyed Paris's position as an international art capital, but also implied a subtle distance from the mainstream French art scene, creating a special category for foreigners and particularly Eastern European Jews.

Also active in Paris was the Ballets Russes, led by the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev, which moved to the city in 1909. Picasso, Matisse, Ernst, Miró, Cocteau, Satie and many other avant-garde figures collaborated with the ballet company, which became one of Paris's most fertile environments for experimentation in dance, music and art.

Special Feature: Marcel Duchamp, 1887–1968

Following on from a year-long exhibition held in 2017 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Marcel Duchamp's Fountain, one of the most controversial art works of the 20th century, this special exhibit marks the 50th anniversary of the artist's death.

There is no sign of Marcel Duchamp in the 2011 film Midnight in Paris, set in the 1920s in a Paris café frequented by artists. The director Woody Allen's exact intentions remain unclear, but Duchamp was in fact totally immersed in chess at the time and had distanced himself from the Paris art scene.

Born in Blainville-Crevon in France's Normandy region in 1887, Duchamp later went to Paris to study art along with his two older brothers. After initially having his painting Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 selected for inclusion in the 1912 Salon des Indépendants exhibition, which dealt with the theme of movement, the Cubist artists overseeing the event abruptly refused to show the work. The painting also created a scandal when it was shown in the Armory Show in New York the following year.

In 1915, Duchamp moved to the U.S., and in 1917, he and his friends caused another stir by submitting a male urinal titled Fountain and signed "R.Mutt" to the first Society of Independent Artists exhibition. While in New York, Duchamp pursued a number of other activities that would help establish his reputation, including conceiving and creating The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (commonly referred to as The Large Glass), and establishing a modern-art organization called Société Anonyme with Katherine Dreier and Man Ray.

In 1924, Duchamp returned to Paris. While devoting himself to chess competitions, he focused on "publishing" projects such as The Green Box, a collection of production notes for The Large Glass, and Box in a Valise, a valise filled with miniature reproductions of the artist's works. Duchamp also designed exhibitions and book covers, but gradually the artist and his Readymades were largely forgotten.

Duchamp moved back to the U.S. during World War II. Some years later, he became the subject of renewed attention after being championed by rising artists such as Robert Rauschenberg. A retrospective of the artist's work held to commemorate the opening of the Pompidou Centre in 1977 belatedly (or for the first time) hailed Duchamp as the "Father of Contemporary Art."

After Duchamp's death in 1968, it was revealed that he had secretly been working on Étant donnés (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas) for many years. Along with this piece, a collection of works amassed by Duchamp's friend Walter Arensberg was gifted to and exhibited at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in accordance with the artist's wishes.

Japanese Western-Style Painting: Contemporaries of FOUJITA Tsuguharu YASUI, Sotaro, Portrait of a Girl, 1912

When Foujita Tsuguharu gained popularity as a painter of l'École de Paris (the School of Paris) in the 1920s, the reactions of his fellow members of the Japanese art world were complex. Some were pleased with the overseas achievements of a young Japanese artist, but others wondered somewhat suspiciously why he was highly regarded in Paris. Foujita earned accolades in Paris with a unique style that could be called distinctively Japanese in character, but in Japan he was often seen as a peculiar figure for living in a Western country and yet not painting in a Western style.

This gap between the recognition he won abroad and the division of opinions on his work in Japan remained after his return to Japan in 1933. Foujita deeply loved his homeland, but it may have been an uncomfortable environment for him as an artist.

What of Foujita's contemporaries in the world of Japanese Western-style painting? Painters such as Koide Narashige, Kuroda Jutaro, and Nabei Katsuyuki were active in the Nika-kai art association, and while Koide died before Foujita returned to Japan, Kuroda and Nabei grew close to Foujita after he too joined Nika-kai. Fujishima Takeji and Miyamoto Saburo were, like Foujita, conscripted to accompany Japanese troops overseas and produce War Record Paintings. Yasui Sotaro and Umehara Ryuzaburo were among the most eminent figures in the Japanese art world of the day.

Of particular interest is Yoshihara Jiro. Originally content to imitate the style of his teacher, he was scolded for this by Foujita – the teacher of his teacher – and increasingly explored his own ideas, eventually developing into a world-renowned artist known for his rejection of imitation. In this sense he carried on Foujita's legacy.

Selected Works of KAWAI Kanjiro from the KAWAKATSU Collection KAWAI, Kanjiro , Vase, 1939

The Kawakatsu Collection, which includes a grand-prize winning piece from the 1937 Paris International Exposition, constitutes the most substantial public collection of Kawai Kanjiro's works in terms of both quality and quantity.

The collection was donated to the museum by the businessman Kawakatsu Kenichi in 1968. When a museum curator went to see Kawakatsu's huge collection of Kawai's works, which placed an entire space of his house, he said, "Choose as many as you like." In the end, 415 items were selected. Along with three pieces that Kawakatsu had previously donated to the museum and seven others that were subsequently added to address a lack of Kawai's early works, the collection eventually totaled 425 works. Made up of important works by the artist, stretching from his first efforts, which were modeled on Chinese porcelain, to his final pieces, made after his involvement with the Mingei movement, the collection is truly a chronological encyclopedia of Kawai's ceramics that spans his entire career.

Kawakatsu (1892–1979), who assembled the collection, worked as the advertising manager at the Tokyo branch of Takashimaya Department Store as well as serving as the store's general manager, and the senior managing director of the Yokohama branch. In his role as a member of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry's craft examination committee, he also strove to foster craft designs.

Kawai's long friendship with Kawakatsu began when he went to meet the artist at the station when Kawai traveled to Tokyo for a meeting regarding the 1st Creative Ceramics Exhibition, which was held at Takashimaya in 1921. Immediately sensing that they were kindred spirits, Kawakatsu began collecting Kawai's works. Reminiscing about the collection, Kawakatsu said, "It wasn't merely based on my personal taste. Sometimes Kawai would make works for the collection and he also chose lots of pieces for it." He added, "It was the crystallization of our friendship."

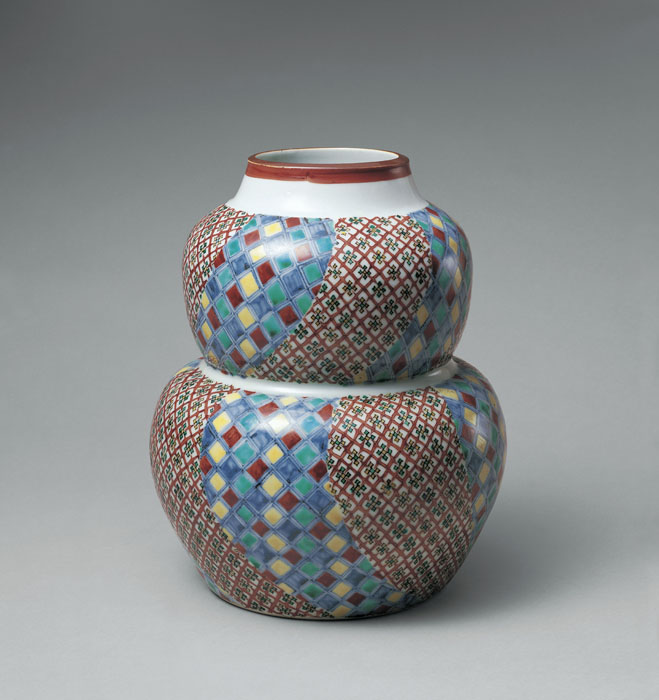

Special Feature: Works of TOMIMOTO Kenkichi TOMIMOTO, Kenkichi, Ornamental Gourd-shaped Jar with Sarasatic Pattern, overglaze enamels, 1944

Concurrently with Foujita: A Retrospective Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of his Death, we are pleased to present a special exhibit of works by Tomimoto Kenkichi, who was born the same year as Foujita and was a fellow student at Tokyo Fine Arts School (present-day Tokyo University of the Arts). Tomimoto is known as a pioneer of modern ceramics, and was named a Living National Treasure in 1955 for mastery of the iroejiki porcelain technique. Throughout his life he continued exploring original approaches, as embodied by his credo of "not making patterns from patterns." Tomimoto did not originally aspire to be a ceramicist, and after graduating from the design department of Tokyo School of Fine Arts and studying abroad in London, he was active in a wide range of fields after returning to Japan, working with various craft media, making prints, and opening a design studio. From this time onward he was admired for the distinctive "taste" of his creations, influenced by the theory and practice of William Morris, which he encountered while studying abroad, and by crafts from around the world that he encountered at what is today the Victoria and Albert Museum. Throughout his career Tomimoto adhered to a philosophy of introducing art into daily life, and viewed popularizing cultured tastes among the general public as a mission no less important than creating art, at one time joining in the Mingei (Folk Art) movement. Tomimoto's "taste" constituted a worldview tinged with the primordial, inspired by primitivism and amateurism, as well as a methodology for engaging with society and daily living, which led him ultimately to choose ceramics as a medium. As a ceramicist Tomimoto expanded his range of endeavor, working with sometsuke (blue and white pottery), white porcelain, multicolored ceramic painting, gold and silver in increasingly splendid pieces, and established a new mode of ceramics as three-dimensional objects in which pattern and form were linked. While doing so, he explored various means of engaging not only the art world but also society in general through his work.

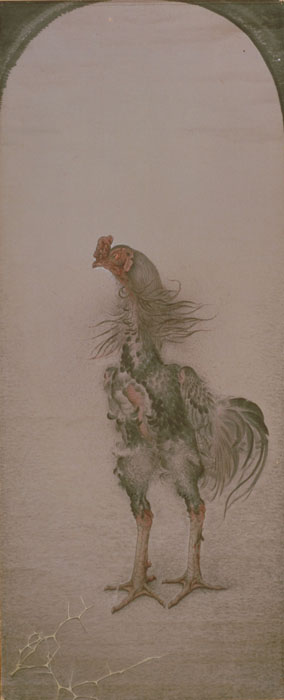

On Nov. 1st, 1918. An Exhibition of Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai has been opened. INAGAKI, Chusei, Fighting Cock, 1919

Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai (National Painting Society) was established on January 20, 1918, with founding members Tsuchida Bakusen, Ono Chikkyo, Murakami Kagaku, Sakakibara Shiho, and Nonagase Banka. Irie Hako also played a significant role in forming the group, but personally felt his work inferior to the others' and chose not to be listed as a founding member, although he later joined after winning the first Kokuten (National Painting Society Exhibition) Prize. The Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai Declaration inspired many young artists by proclaiming respect for individuality, freedom of creativity, and love for nature, and a large number of works were submitted for the first exhibition held in November of that year, not only from Kyoto but also from throughout Japan. The exhibition featured a wide variety of submissions including enchanting female figures, drawings influenced by northern Renaissance art, and highly precise renderings in a Western style, and it developed as a place where emerging artists not accepted in the Bunten Exhibition (art exhibition sponsored by the Ministry of Education) could find a voice. For economic reasons, the society regretfully disbanded after the seventh exhibition in 1928 (members and associates went on to form Shinjusha, but it too dissolved after two exhibitions). However, during the decade of its existence, it enlivened the Taisho Era (1912-1926), when modern Japan started growing toward maturity, with a rich and original if not yet fully realized body of work, and the enthusiasm of its members remains palpable to contemporary audiences today.

Our last exhibition of works from the museum's collection in 2018, the centenary of the group's establishment and of the first Kokuten exhibition, focuses not on founding members, but on other young artists associated with the group. We believe this can reveal more clearly the distinctive character of Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai. (As all of the works in our collection that were originally shown in the Kokuten are currently on loan for "The Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai: Celebrating the Centennial of Its Birth" at Chikkyo Art Museum, Kasaoka, we present other works produced during the years of the Kokuten and Shinjusha exhibitions.)

Exhibition Period

2018.10.16 tue. - 12.16 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Paris as Artistic Community

Special Feature: Marcel Duchamp, 1887–1968

Japanese Western-Style Painting: Contemporaries of FOUJITA Tsuguharu

Selected Works of KAWAI Kanjiro from the KAWAKATSU Collection

Special Feature: Works of TOMIMOTO Kenkichi

On Nov. 1st, 1918. An Exhibition of Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai has been opened.

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

4th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2018–2019 (130 works)(PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)