Collection Gallery

1st Collection Gallery Exhibition 2023–2024

2023.04.21 fri. - 07.09 sun.

Selected Works of Western Modern Art Kurt SCHWITTERS, Untitled (Picture with Wool Ball), 1942/45

This Museum opened 60 years ago, on April 27, 1963, as the Kyoto Annex Museum to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (gaining independence as the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto in 1967). Today the museum’s collection numbers over 15,000 items, of which Western modern art does not account for a large proportion. However, we have acquired a group of important works in this category, with a focus on artistic trends that relate closely to the development of modern art in Japan. Among them are many works and historical materials related to Dada, an iconoclastic movement that subverted the established order and norms of art, questioned its meaning, and opened up new horizons of expression in the 20th century. This time, we are pleased to present works by the Dada affiliates Kurt Schwitters and Max Ernst.

While Dada was originally based in Zurich, Switzerland, artists were engaging in similar activities almost concurrently in other European cities. Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948), a leading figure in Hanover (Germany) Dada whose work spanned the fields of painting, architecture, design, and poetry, is known for “Merz,” his own term for his practice of making assemblages and collages using discarded materials, scraps of paper, tickets and other objects and fragments found on city streets. Underlying this ongoing project was his experience of World War I and his belief that “everything is ruined, the task is to build something new out of the rubble.” This sentiment is reflected in the work shown here, which was created under trying circumstances after he fled to the UK via Norway following the Nazis’ seizure of power in Germany.

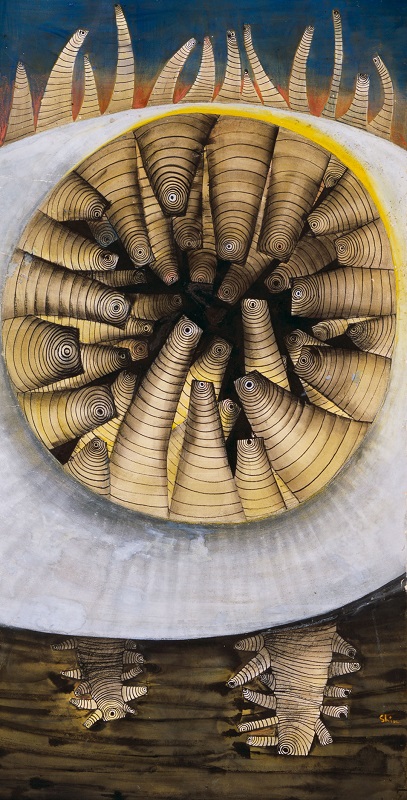

Max Ernst (1891-1976), who participated in Dada activities in Cologne, was also active in a wide range of fields, including printmaking, sculpture, and literature, in addition to painting. His work, which had always had dreamlike qualities, evolved from Dada to Surrealism after he moved to Paris, and he devised original techniques such as frottage, in which paper is placed over an uneven surface and rubbed with graphite or other pigments, and grattage, in which paint on canvas is scraped off with a palette knife. However, what distinguishes the two works on view here are the bizarrely shaped figures depicted therein. Among them, the bird-like figure that Ernst called “Loplop” also appears in many of his other works as a proxy for the artist, mediating between the worlds of image and reality. Although these two works were acquired at different times, they are both from the former collection of Baron and Baroness Urvater of Belgium, who were world-renowned for their outstanding collection of Surrealist art.

The 100th Anniversary of Their Births: Shimomura Ryonosuke / Hoshino Shingo SHIMOMURA Ryonosuke, Echoing Wind, 1992 HOSHINO Shingo, Resolution, 1957

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the births of Shimomura Ryonosuke (1923-1998) and Hoshino Shingo (1923-1997). Also, Shimomura participated in the exhibitions Trend of Contemporary Japanese Paintings in 1963 and Contemporary Trend of Japanese Paintings and Sculptures in 1964, which were held when the museum was still called the Kyoto Annex Museum to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and he relates to the exhibition now on view on the third floor.

Shimomura was born in Osaka, and his father was a Noh theater instrumentalist of the Okura school specializing in the otsuzumi (large hand drum). Birds appeared as a motif in Shimomura’s work at a relatively early stage. According to his own recollections, he narrowed his focus to birds around the fifth year after formation of the Pan-Real Art Association, and after visiting Africa in 1973, he became fond of marabou storks and took to depicting them. However, according to Shimomura's article in the November 1969 issue of Museum Newsletter “Miru”: “Since I started making bird paintings, I have never sketched a bird from life to this day.” This seems to be rooted in his belief that “a painting is essentially a fiction.”

Hoshino was born in Toyohashi, Aichi Prefecture to parents with a penchant for calligraphy and painting. Around the age of 13 he borrowed art supplies from his elementary school teacher and began painting in oils, and at 19 he moved to Kyoto to study art professionally and pursue his own creative path. Hoshino’s style took a turn after the death of his father in 1964. While watching his father's cremation through a peephole, Hoshino witnessed a moment when a side panel of the coffin collapsed, exposing the sole of the deceased’s foot. The intense emotional impact of this experience inspired him to create the Work in Mourning series in an attempt to preserve vestiges of his father. Subsequently, he took this mode of expression one step further with “human prints,” a technique in which vinyl glue is applied to the body, washi paper is pressed against it, and the mark of the human figure is then dusted with mineral pigment. Hoshino’s works reflect his thoughts and feelings toward those who have died, upon which are also superimposed horrific scenes of World War II, and these thoughts and feelings are more directly and effectively conveyed in his human prints.

Both Shimomura and Hoshino studied in the Japanese-style Painting Department of the Kyoto Municipal Specialized School for Painting and were founding members of the Pan-Real Art Association, which aimed to break free from conventions of Nihonga (Japanese-style painting). Shimomura was a lifelong member of the Pan-Real Art Association, and Hoshino belonged to it for about 30 years before withdrawing in 1977.

During the next exhibition of works from the collection, the Nihonga area will introduce the Rekitei Art Association, a predecessor of Pan-Real. What was the nature of the art scene in Japan at that time, into which Shimomura and Hoshino emerged? We look forward to your visit.

Special Feature: Kitaoji Rosanjin KITAOJI Rosanjin, Rectangular Dish, E-oribe Type, 1949

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto opened in 1963, and one of the exhibitions held in this memorable first year was The Art of Rosanjin Kitaoji: Ceramics, Lacquer, Calligraphy, Painting, etc. Born in Kamigamo, Kyoto in 1883, Kitaoji Rosanjin was a titan of the modern Japanese art world, whose activities ranged from calligraphy and seal engraving to ceramics, lacquerware, painting, and culinary arts. In conjunction with the 60th anniversary exhibition Re: Startline 1963-1970/2023 – Sympathetic Relations between the Museum and Artists as Seen in the Trends in Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition, we are pleased to present a special exhibit on Rosanjin, with a focus on his ceramics and lacquerware. Incidentally, of the 35 works by Rosanjin in the museum’s collection, 28 were acquired at the time of our opening.

Rosanjin was prolifically active in numerous fields, but as he himself stated, he was almost completely self-taught. However, he had a keen eye for the classics, and collected countless references and artworks as models for his own study. He was initially drawn to the art of China, but his attention subsequently shifted to Korean and then Japanese art. At the heart of his aesthetic was the world of tea, and the question of how to express a distinctly Japanese worldview in this context. Rosanjin played a central role in the Momoyama tea pottery excavation boom that began in the late 1920s and 1930s, and produced a vast and diverse array of Momoyama Revival ceramics in the styles of Oribe, Shino, Kiseto, Bizen, Shigaraki, Iga, Seto and many others. Most of Rosanjin’s ceramics were made for dining, and were only complete when food was served on them. For this reason, some pieces cannot be fully appreciated as stand-alone ceramic works, but it can be said that this is because his distinctive artistic approach took cuisine as an integral part of his creations. His ceramic production was underpinned by many talented artisans recruited from kilns throughout Japan, but it is said that when Rosanjin made even slight modifications to the work of these artisans, the pieces immediately took on his own signature style. Rosanjin produced lacquerware World War II, when kiln firing had to be suspended, and the charm of these works is enhanced by his open and easygoing approach which contrasts with the meticulous and exquisite techniques of artisans.

Crafts Made in 1963 TAKAMURA Toyochika, Rogin Cylindrical Flower Vase, Lostwax Casting, 1963

The exhibition Contemporary Japanese Ceramic Art, featuring works by Kaneshige Toyo and Okabe Mineo, was held concurrently with Trend of Contemporary Japanese Paintings to mark the opening of the museum.

Sixty years ago, Imaizumi Atsuo, the first director of the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, wrote that “strictly speaking, there is no such thing as criticism in the world of crafts today.” By “strictly speaking,” he referred to the fact that neither praise nor condemnation “could function as a critique of the crafts world as a whole” due to differences in the practices of groups with differing views. In Contemporary Japanese Ceramic Art, ceramics researcher Koyama Fujio presented an overview of the ceramics landscape in Japan at that time, categorizing artists as affiliated with the Nitten (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition), Shinshokai, Kokuten, Sodeisha, Japanese Art Crafts Association, or unaffiliated, and the exhibition also featured antique ceramics and works from overseas. Imaizumi concluded the text cited above by saying “I believe that when a museum of modern art in Kyoto deals with contemporary crafts, it serves as a kind of critical activity,” and perhaps the museum sought to create a space for critique that would offer a bird’s-eye view of “the crafts world as a whole” by exhibiting works by artists occupying different positions and from various periods and regions together in a single exhibition. This approach has since become a basic stance of the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto’s exhibitions and collection.

The following year (1964), the museum held the Contemporary Handcrafts in Japan exhibition, featuring works by Takamura Toyochika, Kiyomizu Rokubey VI, and Shimura Fukumi which were acquired for the collection. Around the museum’s third year, we received the offer of a large donation of works by Kawai Kanjiro, which were unveiled as the Kawakatsu Collection at a 1968 exhibition.

Here, we are pleased to present craft works from the collection that were created in 1963, the year the museum first opened its doors.

*Imaizumi Atsuo, “The Loss of Critique in Contemporary Crafts,” Collected Writings of Imaizumi Atsuo 6, Kyuryudo Art Publishing, 1979 (text first published on June 14, 1963).

Asada Hiroshi's Paintings and Prints after the Trends in Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition ASADA Hiroshi, Original Landscape 〈Heavy Journy〉, 1974

Trends in Contemporary Japanese Art was one of the first exhibition series at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, which opened its doors 60 years ago. Among the artists selected to participate in the series was Asada Hiroshi (1931-1997).

Asada Hiroshi was born in Kyoto. Both his father Asada Benji (1899-1984) and brother Asada Takashi (1928-1987) were practitioners of Nihonga (Japanese-style painting). His father advised him not to become a painter, as a career in art was rife with struggles, but his desire for self-expression was insatiable and he began painting while employed at a company. His first works were semi-abstract depictions of landscapes and objects, and he subsequently began to experiment with a style informed by the Art Informel movement that originated in France and was highly influential in the 1940s and 1950s. Among these is Work C, which he showed at the fourth Trends in Contemporary Japanese Art exhibition in 1965. While Asada was resistant to following trends in principle, he found in this mode of painting challenges that enabled him to find his own path as a painter.

His father began to encourage him on this path, and in 1963 he traveled with his father and brother to Europe, where he was fascinated by classical Western painting and especially that of the Northern Renaissance. This interest in the classics was reflected in his work, giving rise to a unique Surrealist style reminiscent of an associative game of images. He went to Europe again in 1971, and while living in Paris he painted what he called “earth landscape” and “surface landscape,” exploring grand, sweeping imagery which is also described as “original landscape” and “world landscape.” The turning point that led to this development had come in 1965, with his participation in Trends in Contemporary Japanese Art unexpectedly coinciding with the start of an important breakthrough in his artistic practice.

Here we present Asada’s works dating from after the Trends in Contemporary Japanese Art exhibition, through his years in Paris which ended in 1981.

Exhibition Period

2023.4.21 fri. - 7.9 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

The 100th Anniversary of Their Births: Shimomura Ryonosuke / Hoshino Shingo

Two Works that Pose the Question “What is Art”?: Akasegawa Genpei’s Model 1,000 Yen Note and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain

Special Feature: Kitaoji Rosanjin

Crafts Made in 1963

Asada Hiroshi's Paintings and Prints after the Trends in Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition

The Trends in Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition As Seen in Works from the Collection

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

1st Collection Gallery Exhibition 2023–2024 (142 works in all) (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Hours

10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

*Fridays: 10:00 AM – 8:00 PM

*Admission until 30 min before closing.

*Opening hours is subject to change, due to the prevention against COVID-19 pandemic.

Please check the updated information, before your visit.

Admission

Adult: 430 yen (220 yen)

University students: 130 yen (70 yen)

High school students or younger,seniors (65 and over): Free

*Figures in parentheses are for groups of 20 or more.

Collection Gallery Free Admission Days

April 22, May 18, July 8, 2023

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)