Collection Gallery

3rd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2022–2023

2022.07.22 fri. - 10.02 sun.

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

This area features outstanding Western modern art from the museum’s collection or deposited with the museum. Currently, we are pleased to present works by Kurt Kranz (1910-1997), who studied at the Bauhaus and taught a foundation course in visual arts theory at the University of Fine Arts of Hamburg for many years.

Kurt Kranz was born in Emmerich, Germany near the Dutch border, and as a young child moved with his family to Bielefeld, Germany. He trained as a lithographer from 1925-30 while attending evening classes at the Bielefeld School of Arts and Crafts, and studied a wide range of artistic genres and theories. Kranz, who had studied lithography as a commercial design medium but was more interested in abstraction than in figuration, attended a lecture about Bauhaus classes by László Moholy-Nagy in Bielefeld in 1929. Profoundly impressed, he showed Moholy-Nagy his own work, and was encouraged to study at the Bauhaus. In 1930 Kranz enrolled at Bauhaus Dessau, where he studied under Josef Albers and Joost Schmidt while also experimenting with photography at Walter Peterhans’s recently opened photo workshop. Kranz was also greatly influenced by the art theories of Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. He received his diploma in 1933, just before the Nazis forced the Bauhaus to close, and from 1933-38 he worked as a commercial designer at Dorland Studio, headed by Herbert Bayer, in Berlin. During World War II he served in Finland and Norway, and after the war he was a professor at the University of Fine Arts of Hamburg from 1950 until his retirement in 1972.

His artistic interest always lay in the deployment of basic formal elements, such as lines and planes, in diverse variations. This was not limited to horizontal and vertical movement but also encompassed compositional depth of field, as exemplified by close-ups and fadeouts. In his works he arrayed individual images in sequences, like frames in a film or animation. In doing so he frequently employed the format of leporello, a type of binding for folded leaflets also known as concertina or bellows binding. The works exhibited here, subtitled “Folding Object,” feature collaged leporello unfolded in their centers, and gradually shifting variations of shapes and colors are skillfully arranged throughout the works so as to synchronize the collages with the background images. By tracing these variations with their eyes, viewers can spatially and temporally experience the light-footed movements of a harlequin or the serenity of a stone garden. Kranz’s methodology appears to be informed by cognitive psychology, and has been described, in the words of Kranz’s friend the philosopher Max Bense, as Die Programmierung des Schönen (“Programming Beauty”).

Tradition / Innovation MORI Kansai, Goose, 1868-1912

[on View: Jul. 22–Aug. 28] TSUCHIDA Bakusen, Women in Paris, 1923

[on View: Aug. 30–Oct. 2]

Up until the Edo Period (1603-1868), almost all Japanese paintings were in the form of picture scrolls, hanging scrolls, folding screens, paintings on sliding doors or partitions, or fans. Most Japanese paintings of the Meiji Era (1868-1912) also followed these traditions, but with the influence of Western painting, Japanese paintings (known as Nihonga to distinguish them from Western-style Japanese paintings or Yoga) gradually came to be framed. In addition to officially sponsored open-call art exhibitions such as the Bunten (Ministry of Education Art Exhibition) and the Teiten (Imperial Art Academy Exhibition), exhibitions by non-officially sanctioned groups such as the Inten (Exhibition of the Japan Art Institute) and the Nika Association’s Nika Art Exhibition began to be held, and changes in format gained momentum.

In Kyoto, Tsuchida Bakusen, Ono Chikkyo and others formed Kokuga Sosaku Kyokai (the National Creative Painting Association) in 1918, and the group held exhibitions open to non-members. Seeking creative freedom in painting, they produced innovative Nihonga works. From the Meiji Era onward many painters went abroad to study, and the latest overseas artistic developments were reflected in Nihonga.

Soon after World War II, in 1948, Mikami Makoto, Hoshino Shingo, Yagi Kazuo, and others formed a group known as Pan Real, but the ceramic artists Yagi Kazuo and Suzuki Osamu withdrew not long after, and the following year the group was relaunched as the Pan Real Art Association and limited its activities to Nihonga. Members of the association including Mikami, Hoshino, Shimomura Ryonosuke, and Fudo Shigeya carried out innovative experiments as they endeavored to break free of conventions of the genre.

Each period of history has seen drive toward innovation in Nihonga, and the creation of new styles that reflected the times. At the same time there have been painters who continued to work in the mode of the Rinpa school and to depict traditional subjects, as in flower-and-bird paintings, handed down from generation to generation, creating original works of art within the context of traditional expression.

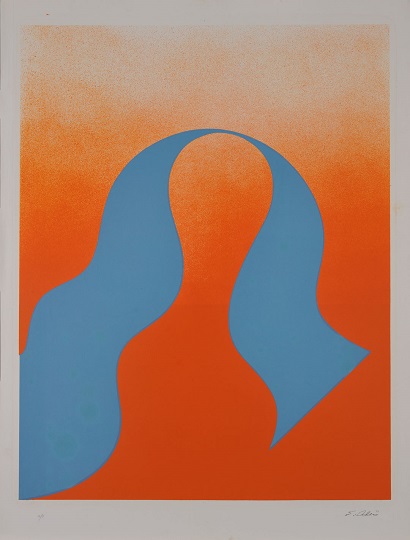

Cool, Hard, and Erotic: Form and Color in Prints IDA Shoichi, Fountain, 1968 IDA Shoichi, Weekday, 1968

In this section, we focus on prints from the 1960s and ’70s, the era in which Kiyomizu Kyubey made his debut as a sculptor. Distinctive features of Kiyomizu’s works such as concise geometric shapes, lucid colors, and sharp outlines resonate with contemporary art trends (especially those in America) such as the Primary Structures and Hard-edge movement in which artists tired their utmost to eliminate any trace of the hand.

Influenced by Mondrian’s geometric abstractions among other things, Murai Masanari emerged as a pioneering figure in Japanese abstract painting. Meanwhile, Saito Yoshishige, who took cues from Dadaism and Russian Constructivism, created relief-style works using simple forms and color schemes. The artists’ approach to color and form are rooted in the simplification and abstraction of organic forms – lessons they learned from Jean (Hans) Arp’s woodblock prints and sculptures, and Henri Matisse’s paper cut-outs.

Amid the international print boom of the 1960s, Ida Shoichi was hailed for his lithographs, which made systematic use of color planes. The works were especially notable for their relaxed rhythm and unique eroticism, realized through a repetition of wave-shaped curves. Takahashi Shu cloaked erotic themes in compositions distinguished by bright colors and embossing. And Sugai Kumi, who had previously worked as a commercial designer, adopted geometric figures and stripes that recalled traffic lights and railroad-crossing gates in prints and paintings that evoke the geometric abstractions of the Hard-edge movement. A similar creative attitude can be seen in the stenciled works of Asada Shuji, a member of the Mugendai dyeing collective. Variously described as cool, hard, and erotic, these abstract expressions, with their deft use of color and form, make for enjoyable viewing.

KIYOMIZU Rokubey V-VI and KAWAI Kanjiro KIYOMIZU Rokubey Ⅴ, Incense Burner, Flower and Bird Design, Taireiji Type, 1917

Surveying the ceramic art career of Kiyomizu Kyubey / Rokubey, one becomes aware of the Rokubey family’s prominence as makers of Kyo-yaki ware. This section presents works by Kiyomizu Rokubey V and VI and by Kawai Kanjiro, all of whom consistently created works reflecting their times in the field of ceramics––a field with multifaceted values as both an industry and an art form.

Rokubey V (1875-1959) was known for a style informed by Chinese ceramics and the Rinpa school, and his Otowa Ware of 1913 and Taireiji Porcelain of 1915 are particularly representative of his style. The influence of the Kyoto City Ceramic Research Institute, which was established in 1896 and was one of the first institutions to incorporate Western trends into its practices, can also be seen. Otowa Ware was innovative for its bold patterns and colors, created by applying majolica and thickly applying paint, as well as utilizing the texture of matte glaze. In 1927, the 8th Teiten (Imperial Art Institute exhibition) was the first to have a Crafts section, and crafts gained official status as an art form. Rokubey V was the only Kyoto ceramic artist selected to serve on a jury that included Itaya Hazan and others.

Rokubey VI (1901-1980) was the youngest artist to have work selected for the 8th Teiten, his Flower Vase with Macaw, Pale-blue and Purple Glaze appeared in the 9th Teiten, and he went on to show works primarily in the Teiten and its postwar successor the Nitten (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition). Rokubey VI worked in a wide range of styles, but in particular the Genyo Type of 1955, the Shuyo Type of 1953, and the Kokisai Type of 1971, the last of which was unveiled to commemorate his 70th birthday, are glazing techniques representative of the artist’s work, which is often noted for its great elegance.

It is intriguing to contrast the work of the Rokubey family with that of Kawai Kanjiro (1890-1966). Kawai was born in Shimane Prefecture, studied ceramics at Tokyo Higher Technical School (now Tokyo Institute of Technology), and moved to Kyoto in 1914 as a technician at the Kyoto City Ceramic Research Institute. His close association with the Rokubey family began in the formative period before he became an independent artist. After resigning from the Institute he spent two years as a technical adviser to Rokubey V, and in 1920 he took over the latter’s kiln and named it Shokeiyo, making it his base of operations for the rest of his life. As exemplified by his co-signing the Prospectus for the Establishment of the Japanese Folk Crafts Museum in 1926, he focused on the beauty found in daily vessels and applied it to his own work, which was presented mainly in solo exhibitions.

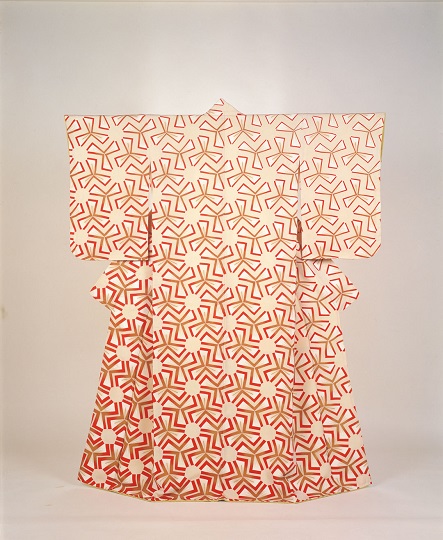

Kyoto Crafts MORIGUCHI Kunihiko, Yuzen Kimono, “A Thousand Flowers”, 1969

For centuries, as the imperial capital of Japan, Kyoto was also the country’s cultural center. However, in the Meiji Era (1868-1912) Kyoto lost this position with the transfer of the capital to Tokyo, and the threat of the city falling into decline led to a strategic attempt to develop a new image of Kyoto as an ancient city with a luxurious and elegant atmosphere. During this period many artisans adopted the appellation “Heian” (a reference to Heian-kyo, a name for Kyoto in antiquity). In this sense, it can be said that modern and contemporary Kyoto crafts took skillful use of the ancient capital’s image as a point of departure, and subsequently developed into its current form.

This small exhibit presents seven works from the museum’s collection by Kyoto-based artisans. These are artists who worked in modern-day Kyoto after the tumultuous period described above, and they did not particularly strive to produce a classical “Kyoto-esque” image. However, they all shared the goal of drawing creative nourishment from the city’s deep cultural roots while also exposing themselves to new and innovative ideas. It is well known that Mingei (Folk Crafts), a crucial modern crafts movement, had its origins in Kyoto, and Kuroda Tatsuaki was a key member of that movement. Another influential group founded in Kyoto was Sodeisha, a circle of ceramic artists that counted among its founding members Suzuki Osamu, who was a leading figure in postwar avant-garde ceramics. Meanwhile, Moriguchi Kunihiko has opened up a new world of Yuzen dyeing by boldly combining geometric patterns with graphic design principles he studied in Paris, while Kato Sogan, Nakai Teiji, Hattori Shunsho, and Ito Hiroshi, primarily exhibiting at the annual Nitten (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition), have developed an imposing and yet glamorous creative vision by combining motifs from literature and nature with decorative elements.

AI-MITSU and Still-Life Painting AI-MITSU, Still Life, 1942

Ai-Mitsu (1907-1946), a painter active in the 1920s and 1930s, is known for his Surrealist style of the 1930s, and for his untimely death at the age of 38 after World War II disrupted his artistic career. Most of his works did not survive the war, as he was from Hiroshima and many of them were destroyed by the atomic bombing, but this museum succeeded in newly acquiring one of his oil paintings, Still Life, in 2020. This brings the number of his works in the museum’s collection to three, all of which are in fact still-life paintings. This can be seen as speaking to the nature of his artistic development.

Ai-Mitsu’s brief career was a series of diverse experiments and sudden transformations, but his basic stance was rooted in realism, and still-life painting was evidently a testing ground for his ideas. It is said that he would not feel comfortable painting an object until he had thoroughly examined it, scrupulously observed it, and was fully satisfied with what he saw. His studio contained a wide range of objects such as plants and stones, and one anecdote tells of him acquiring a bird to cook and eat, only to observe it for so long that it decayed into a skeleton. The French equivalent of the English phrase “still life” is nature morte, literally “dead nature,” and Ai-Mitsu indeed sought to find living forms in dead organisms while observing the transformations that animals and plants undergo. In this sense his work is in the spirit of traditional East Asian flower-and-bird paintings (sketches from nature), which aimed to depict plants and animals as living things, and in fact he took a strong interest in sketches from nature of Song and Yuan dynasty China.

This exhibit features three still-life paintings by Ai-Mitsu, as well as a range of modern Japanese Western-style oils and watercolors of the same genre.

Special Feature: MIO Kozo

Mio Kozo was a Kyoto-based painter who was born in the same city as Kiyomizu Kyubey (1922-2006), whose retrospective exhibition is being held on the third floor, and who was also active in Kyoto. The two of them also taught at the same school, and while they worked in different genres, the painter Mio was a friend of the sculptor and ceramicist Kyubey. In this area, we are pleased to present Mio’s works in conjunction with the Kiyomizu Kyubey / Rokubey VII Retrospective exhibition.

Mio Kozo, born in Nagoya in 1923, was expected to succeed the family business, a clinic, but failed his entrance exams. In 1942, he enrolled at the Kyoto Municipal Special School of Painting (preparatory course in Nihonga, i.e. modern Japanese-style painting) on his father’s advice. Personally, however, he wanted to study oil painting, so he also attended the Murasakino Institute of Western Painting headed by Ota Kijiro. After graduation, he returned to his hometown to teach art at a junior high school and abandoned Nihonga. In 1950 he moved to Kyoto to teach at another junior high school, and again attended the Murasakino Institute of Western Painting. In 1951, through his brother Fumio, a Western-style painter, he was introduced to Kito Nabesaburo, and showed work in the Kofu-kai Exhibition. He was nominated as a member of Kofu-kai in 1959. After working with cement as a material and experimenting with abstraction, he withdrew from Kofu-kai in 1964, intending to break away from conventional painting. With the goal of creating a new painting style, he discarded all the art supplies he had used thus far and continued to explore and experiment, arriving in the late 1960s at his own distinctive style that involved spraying acrylic color on wooden panels with an airbrush. Beginning with photographically realistic images of women, he distorted, deformed, subdivided, and montaged them to create extraordinary pictures that evoke afterimages, illusions, and mental landscapes. In 1969 he was selected to represent Japan at the 10th São Paulo Art Biennial, and thereafter he was active both in Japan and overseas. Meanwhile, he became an assistant professor at Kyoto City University of Arts in 1971 and a full professor at the same university in 1975, enthusiastically teaching young aspiring artists. He received the Mainichi Art Award in 1991 and the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’s Art Encouragement Prize in 1997, and was designed a Person of Special Cultural Merit by Kyoto Prefecture in 1998. Mio also created the cover art for the weekly photography magazine Focus for 18 years, beginning with its first issue in 1981, so many viewers may be familiar with his style.

Exhibition Period

2022.07.22 fri. - 10.2 sun.

[First term]

7.22 fri.~8.28 sun.

[Second term]

8.30 tue.~10.2 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

Tradition / Innovation

Cool, Hard, and Erotic: Form and Color in Prints

KIYOMIZU Rokubey V-VI and KAWAI Kanjiro

Kyoto Crafts

AI-MITSU and Still-Life Painting

Special Feature: MIO Kozo

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

3rd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2022-2023 (157 works in all) (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Hours

10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

*Fridays: 10:00 AM – 8:00 PM

*Admission until 30 min. before closing

*Opening hours is subject to change, due to the prevention against COVID-19 pandemic.

Please check the updated information, before your visit.

Admission

Adult: 430 yen (220 yen)

University students: 130 yen (70 yen)

High school students or younger,seniors (65 and over): Free

*Figures in parentheses are for groups of 20 or more.

Night Discount for Collection Gallery

Adult: 220 yen

University student: 70 yen

*The Discounted admission is only available after 5 P.M. on Fridays

*Admission until 30 minutes before closing.

Collection Gallery Free Admission Days

July 23, October 1, 2022

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

![MORI Kansai, Goose, 1868-1912 [on View: Jul. 22–Aug. 28]](https://www.momak.go.jp/English/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/08/2022CG3_img08-432x1024.jpg)

![TSUCHIDA Bakusen, Women in Paris, 1923 [on View: Aug. 30–Oct. 2]](https://www.momak.go.jp/English/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/08/2022CG3_img09.jpg)