Collection Gallery

4th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2020–2021

2020.12.24 thu. - 03.07 sun.

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

In this section, we present outstanding works of Western modern art that are contained or deposited in the museum collection. In this edition, we focus on three deposited paintings by Maurice Utrillo (1883-1955).

Utrillo was born in Paris in 1883. He was the illegitimate son of Suzanne Valadon who, in addition to serving as a model for artists such as Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec, was a painter in her own right. Utrillo’s surname was derived from Miguel Utrillo i Morlius, a Barcelona aristocrat and art journalist, who acknowledged paternity. Utrillo’s mother later married twice, but he retained the name until the end of his life. Absorbed in her own life and work, Valadon left Utrillo with her own mother, who raised him in the suburbs of Paris. However, after starting junior high school in the French capital, Utrillo was driven to drink by a feeling of loneliness, and quickly succumbed to alcoholism. In 1904, at the age of 20, Utrillo took up a brush as part of his treatment for the affliction, essentially teaching himself how to paint. Utrillo was subsequently involved in a string of scandalous events related to his drinking, and repeatedly hospitalized in mental institutions. Meanwhile, he painted landscapes, primarily in the Montmartre district, where he lived.

Country Church (1911) and Mimi Pinson's House at Montmartre (1915) date from Utrillo’s most notable “white” period (1910-1916). The works are distinguished by the texture of the walls. To successfully depict these plaster walls, Utrillo mixed white materials, such as lime, eggshells, and sand, with paint. In Country Church, the road leading to the church curves to the left, while in Mimi Pinson's House at Montmartre, the road leads down the hill before suddenly stopping in the middle. Both works prevent us from seeing what lies us ahead. The paintings – one focusing on a church, with its artless spire and multiple roofs, and the other, a red-walled house, equipped with several towering chimneys – suggest Utrillo’s inability to foresee his own future. Saint-Rustique Street, a narrow way leading to Sacré-Cœur Basilica, which stands atop a hill in Montmartre, was painted in 1921. The same year, Utrillo was arrested for public indecency. After being imprisoned, he was committed to a mental hospital, having been judged legally incompetent. Based on these circumstances, it would have been hard for Utrillo to paint the realistic picture while gazing at the actual landscape. As it turns out, he repeatedly painted the typical landscape in Montmartre, known for the famous Lapin Agile cabaret, referring to commercial picture postcards with the same sceneries. The work, part of Utrillo’s “color” period, contains the reduced physical texture, and is distinguished instead by the power of its black lines. But as with the other two works, the road extending into the rear curves, leaving no clear way of reaching the basilica.

To Utrillo, the Montmartre landscape was more than a subject for his paintings. By depicting this area where he lived, Utrillo was in effect painting himself. This is borne out by Jean Cocteau who, while recalling the windmill at the Moulin de la Galette dance hall, addressed a following sentence in his obituary for Utrillo:

“The windmill, the miller absent, is the wings anymore not fly”

The Drawn Buildings ITO Hakudai, Night View at Kiyamachi, 1915

How are buildings depicted in Nihon-ga (Japanese-style paintings)? One example that might come to mind are the roofless houses that appear in scroll paintings. Another familiar example can be found in rakuchu rakugaizu (“scenes in and around Kyoto”) screen paintings, which are filled with depictions of buildings. There are also buildings in pictures of notable places, which in ancient times were based on tanka poems, and depictions of temples and shrines in miya (shrine) and sankei (pilgrimage) mandalas.

The Edo Period (1603-1868), an era marked by the flourishing of empirical learning such as Dutch studies and herbalism, saw the advent of pictures that depicted real scenes in landscapes and sketches. In addition, the construction of roads led to a travel boom, and in turn the production of ukiyo-e prints, which depicted post towns and sightseeing spots.

In the Meiji Period (1868-1912), Western things of all kinds became a common sight in Japan, further increasing the awareness of realism. Moreover, the work of the French Barbizon school of painters, who placed a strong emphasis on natural observation and depictions of forests and rural landscapes, were introduced to Japan, greatly inspiring local artists. Nihon-ga painters not only studied ancient paintings and copies of old books, they went outdoors and began sketching things they saw with their own eyes, using these sketches as the basis for their finished works. Old-style landscapes gave way to a new kind of landscape paintings, and buildings, which had originally been little more than a single element in the scenery, came to play a major part in the pictures.

As time went on, the expressive style of Nihon-ga also grew increasingly diverse. In response to abstraction and other foreign art trends of the era, a new generation of painters emerged, striving to develop a new kind of Nihon-ga, and unrestrained by preconceived notions, opening up possibilities in the genre.

Educational Studies 02: Yuta Nakamura “What’s in the Vase?” ISHIGURO Munemaro, Vase "Late Autumn", c. 1955

Opening Senses: Project to Promote Innovative Art Appreciation Programs is a series of events presented at the museum that are designed to explore new ways for anyone, regardless of whether they are visually impaired or sighted, to enjoy art. In fiscal 2020, an artist, a visually impaired person (Blind), and a curator made the most of their professional skills and sensibilities to establish the ABC Project as a means of creating methods of art appreciation based on different senses. This year the participants joined forces to search for a new way to enjoy Ishiguro Munemaro’s work Vase: Late Autumn.

Ishiguro (1893-1968) founded the Yase Kiln in Yase (a neighborhood in Sayoku Ward, Kyoto) in 1936, and dedicated himself to making ceramics in the area until the end of his life. When he was designated a Holder of Important Intangible Cultural Properties (or a Living National Treasure) of iron-glazed ceramic techniques in 1955, Ishiguro was presented as a modern independent artist, who pursued ancient ceramic traditions from China and Korea. However, the pot shards that were abandoned by him in the area took on a new aspect due to the great pains he took to make ceramics.

This project began by digging up some pot shards. Next, Nakamura Yuta studied the fragments and his original work, and Yasuhara Rie felt and described the shards in order to shed light on the artist’s ceramic creations. Moreover, the curator observed these operations and formed a link with the museum collection. In this edition of Educational Studies, the participants honed their visual and aural senses, touching each of the shards in the vase and listening to the dialogue that occurred between Nakamura and Yasuhara about the ceramic fragments in Yase in order to discover a new means of appreciating Vase: Late Autumn. In addition, ABC Collection Studies: The Ishiguro Munemura Pot Shard Collection, in which the three participants offered their own perspectives on the artist’s pot shards, was published on the museum website.

(Special cooperation provided by the Kyoto Seika University Center for Innovation in Traditional Industries.)

Links to ISHIGURO Munemaro: KITAOJI Rosanjin, YAGI Kazuo, and SHIMIZU Uichi KITAOJI Rosanjin, White Jar with Letters of Blue-and-White, 1949

Possessing a unique perspective on the distinguishing characteristics of classical art, Ishiguro Munemaro pursued creative work in which he brought these elements to life. Highly acclaimed for his technique and artistry, Ishiguro was designated a Holder of Important Intangible Cultural Properties (or a Living National Treasure) for his iron-glazed ceramics in 1955. By studying ancient clay and pot shards, Ishiguro taught himself various ceramic methods while developing relationships with a wide array of artists.

Kitaoji Rosanjin, an artist at the forefront of a movement to revive the classic in the early Showa era, shared stylistic similarities and a creative ethos with Ishiguro. At the same time, Rosanjin displayed a variety of talents, including not only ceramics but also calligraphy, seal engraving, painting, lacquerware, and cooking. In a text by Ishiguro called “Kitaoji-san and Me,” he recounts a visit he made to Rosanjin. After describing the artist’s obstinate character, Ishiguro wrote, “As ever, talk becomes animated when the topic turns to something delicious.”

Yagi Kazuo is known as a pioneer in the creation of obje-yaki. At first glance, Yagi and Ishiguro seem to be far removed from each other. But like Ishiguro, Yagi was strongly attracted to old Chinese and Korean pottery, and he painstakingly worked to incorporate the power of these classic works in contemporary forms of expression. Recalling a visit Yagi made to Ishiguro’s house in Yase, he wrote, “I was impressed by his sensibility, which lives on in the contemporary era, his elegant taste, and his creative assurance and flexibility.”

Like Ishiguro, the potter Shimizu Uichi was designated a Holder of Important Intangible Cultural Properties for his iron-glazed ceramics. He also apprenticed with Ishiguro when he was 14. But due to the growing strength of the wartime regime, Shimizu’s time as an apprentice ended after only a few months. Despite this, Shimizu’s first-hand experience of Ishiguro’s creative realm determined the direction he later took in his art.

Modernism in Japanese Crafts NIHASHI Biko, Handbox with Bird and Flower Design, 1929

In Japanese crafts, the advent of so-called “independent artists” did not begin until the early 20th century. In 1927, the government-sponsored Bunten exhibition added a fourth division for crafts, leading the genre to be incorporated into the art system both in name and reality. One person who received a special prize at the exhibition was the metal artist Takamura Toyochika. Takamura was one of the central figures in the movement to have crafts recognized as art. He established organizations such as the Soshoku Bijutsuka Kyokai, Mukei, and the Jitsuzai Kogei Bijutsukai, which proved to be extremely important in the history of crafts, and exerted a strong influence on the state of crafts in art. Takamura’s works, including the prize-winning piece in the Bunten exhibition, are characterized by an Art Deco-style centering on geometrical forms.

Art Deco first achieved world renown after it was introduced at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris. These works were more reminiscent of geometry and industrial products than the organic curves of Art Nouveau. Takamura’s former teacher Tsuda Shinobu served as a Japanese judge at the exposition. After returning to Japan, Tsuda extolled the application of the Modernist ethos to Japanese crafts, primarily metalwork, leading Art Deco to become popular in Japan at the same time as the rest of the world. The style’s influence was multifaceted, emerging not only in metalwork but also in the fields of ceramics and lacquer.

In conjunction with 100 Years of BUNRIHA: Can Architecture Be Art?, we present this exhibit of Art Deco-style Japanese crafts, which took the craft world by storm, and flourished around the same time as the Bunriha Kenchikukai, which was formed in 1920.

SOGAME Hirotaro and “Colorists” in Kansai SOGAME Hirotaro, Morning, 1922

The first Nika-kai exhibition, held in October 1914, was established by a group of painters who had broken away from the Ministry of Education’s Bunten exhibition. The event was acclaimed for the work of one new artist. According to the watercolorist, Miyake Kokki, the six works shown by Sogame Hirotaro (1889-1951) were notable for “a kind of power, refreshing colors, and a buzz in the air.” While the new approaches of Kishida Ryusei and Yorozu Tetsugoro were attracting attention in Tokyo, Sogame was being esteemed as a “colorist” for his similarly novel experiments in Osaka and Kyoto.

Sogame was born in Osaka, and his decision to pursue art was influenced by his uncle, the painter Yoshida Hatsusaburo. He later enrolled in the Kansai Bijutsuin (Fine Arts Academy of Western Japan) in Kyoto against his father’s wishes. Kanokogi Takeshiro was the head of the school at the time, and the curriculum was based on a rigid form of academism. But Sogame was apparently inspired by a number of former Kansai Bijutsuin students, such as Tsuda Seifu and Umehara Ryuzaburo, who had recently returned from studying in Europe, to buy foreign publications at Maruzen bookshop and research the new art that was emerging from the West. Despite being an unknown newcomer, Sogame was awarded second prize in the Nika-kai exhibition.

However, Sogame’s career was interrupted not long after. Feeling threatened by news of the prize, Sogame’s father sent him to live in his uncle’s hometown of Saijo, Ehime Prefecture, and demanded that he give up art. Even so, Sogame refused to abandon painting, and in 1920, with the help of Sakamoto Hanjiro and others, he moved to Tokyo and resumed his career. He subsequently devoted himself to making moderately realistic landscapes.

2021 marks the 70th anniversary of Sogame’s death. Here, along with a number of the artist’s own pictures from the museum collection, we showcase works by other Kyoto and Osaka painters of the era in a retrospective of the Colorists, who shone in the Kansai region during the early Taisho Period.

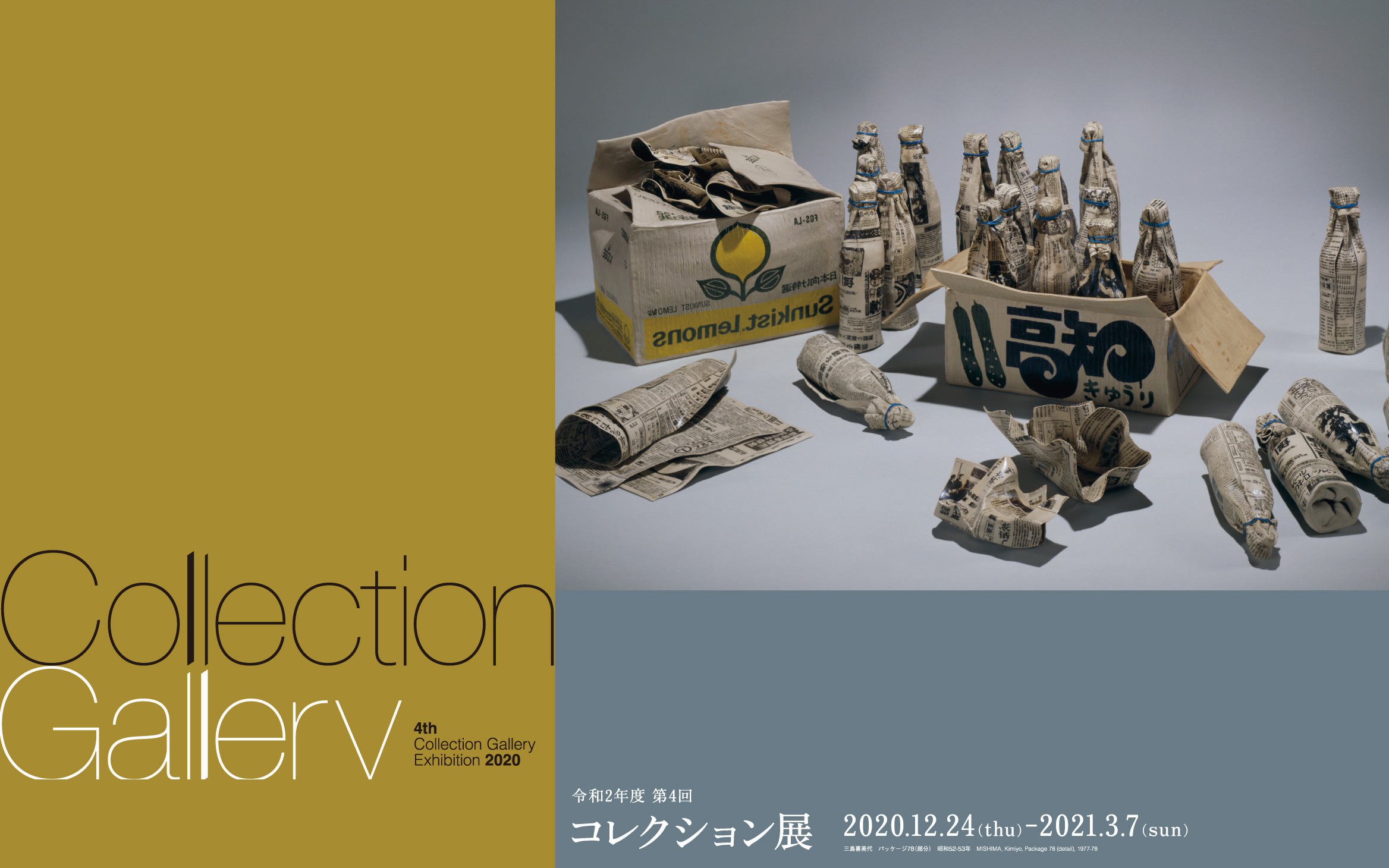

Special Feature : MISHIMA Kimiyo MISHIMA Kimiyo, Package 78, 1977-78

Born in Osaka in 1932, Mishima Kimiyo focused on painting until the early 1970s, receiving acclaim for her collage-style two-dimensional works. In 1965, Mishima received the Shell Art Award. Then, in the early ’70s, she turned her attention to ceramics. After first being selected for inclusion in the avant-garde division of the Japan Ceramic Art Exhibition, Mishima’s work was included and awarded prizes in countless open-call exhibitions, and she was invited to take part in domestic and foreign exhibition. Mishima remains tirelessly active to the present day.

The majority of Mishima’s ceramic pieces feature silkscreen transfers of type from the pages of newspapers and magazines, and cardboard boxes bearing trademarks. Due to the breakable quality of the material, Mishima chose ceramics as the most suitable medium to express a sense of unease, anxiety, and crisis. Initially, she set out to convey the danger of being submerged in information. Later, by switching her focus to the way in which information becomes garbage (for example, mass quantities of handbills, newspapers, and magazines are quickly thrown away), Mishima arrived at her present style in which she uses time and money to make ceramic expressions of discarded waste. In this way, the artist takes a humorous approach to this unparalleled relationship between the huge amount of information and garbage, a peculiar facet of present-day society. At the same time, Mishima expresses the mentality of contemporary people, whose lives are threatened by an excess of information.

The museum had previously acquired Mishima’s early ceramic work Package 78 and three of her paintings. Then, after adding some of her more recent ceramic pieces to the collection in fiscal 2019, it has become possible to better trace the trajectory of Mishima’s work. Thus, in this exhibit, we are pleased to present Mishima Kimiyo’s world of art, which has generated an increasing amount of international acclaim in recent years.

Exhibition Period

2020.12.24 thu. -2021.03.07 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

The Drawn Buildings

Educational Studies 02: Yuta Nakamura “What’s in the Vase?”

Links to ISHIGURO Munemaro: KITAOJI Rosanjin, YAGI Kazuo, and SHIMIZU Uichi

Modernism in Japanese Crafts

SOGAME Hirotaro and “Colorists” in Kansai

Special Feature : MISHIMA Kimiyo

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

4th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2020–2021 (97 works in all) (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Hours

9:30AM–5:00PM

*Fridays and Saturdays: 9:30AM–8:00PM

Evening Extended Hours Will Be Suspended from January 16 until further notice.

*Admission until 30 min. before closing

*Opening hours is subject to change, due to the prevention against COVID-19 pandemic. Please check the updated information, before your visit.

Admission

Adult: 430 yen (220 yen)

University students: 130 yen (70 yen)

High school students or younger,seniors (65 and over): Free

*Figures in parentheses are for groups of 20 or more.

Night Discount for Collection Gallery

Adult: 220 yen

University student: 70 yen

*The Discounted admission is only available after 5 P.M. on Fridays and Saturdays

*Admission until 30 minutes before closing.

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)