Collection Gallery

2nd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2020–2021

2020.07.22 wed. - 10.04 sun.

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

In this section we are pleased to present some of the finest works of Western modern art belonging to or deposited to the museum. Here we focus on the works of Claude Monet (1840-1926), one of most important French Impressionists and an artist enormously popular in Japan as elsewhere. Having passed the age of 40, Monet moved in 1883 to Giverny, where he was to live for the rest of his days. Around the same time, human figures disappeared from his paintings, and his interest turned to representation of ever-changing natural phenomena.

The Epte River was very close to his new home, and was the site of his 1890s series Poplars. Prior to this, in 1885 he produced Willows in Springtime, Bank of the Epte River, in which two willow trees beside the Epte River are rendered against a backdrop of poplar trees. The painting is divided into four horizontal bands, showing in descending order the blue sky, trees with buds just starting to open, lush new spring grass, and the river’s surface reflecting the scene. In contrast to this horizontal aspect, two willow trees and their reflections, visible on the river, extend vertically across the painting. By employing a composition that does not rely on traditional perspective, Monet emphasized that the subject of the work is not the landscape itself, but the depiction of contrasts in the early spring light illuminating the landscape. Monet referred to ukiyo-e by Hiroshige and Hokusai in arriving at the new approach to landscape seen in this work.

Nearby to the west of Monet’s Giverny’s home were the Clos Morin Farm, and after summer drew to a close bundles of wheat ears, not yet threshed, were piled into round stacks like giant spindles. These haystacks, as such heaps of grain are generally called, became the subject of Monet’s first full-fledged series. In all he produced 30 of these works, five in 1888-89 and 25 in 1890-91. Grainstacks, Giverny, Morning Effect is one of the five earlier paintings. Behind the haystacks, in the distance beyond the farm and the river Seine, is a hill thought to be Port-Villez, suggesting that Monet faced southwest when working on this painting. Further evidence of this can be seen in the haystacks’ and the surrounding landscape’s exposure to the morning sun from the east, which brilliantly illuminates them while blurring their outlines. In the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Saitama is Grainstacks at Giverny, the Evening Sun, painted around the same time and depicting the haystacks from the same point, but in contrast to this work, the haystacks at sunset are virtually reduced to silhouettes.Grainstacks was the forerunner of other series by Monet including Poplars and Rouen Cathedral, and it has also been noted that his choice of theme may have implied a celebration of France’s abundance as an agricultural nation following the Franco-Prussian War.

The Folding Screen Festival TSUCHIDA Bakusen, Woman Divers (Right Screen), 1913 [on View: July 22–August 23] TOMIOKA Tessai, Distant View of Mt. Fuji・Autumn View of Kankakei (Left Screen), 1905 [on View: August 25–October 4]

On July 17 and 24 of every year, processions of splendidly decorated yamahoko floats are called Saki matsuri (early festival) and Ato matsuri (later festival), which are the best-known highlights of the Gion Festival. The two nights preceding each of these are called yoiyama and yoiyoiyama (pre-procession and pre-pre-procession events), when people in light summer kimono walk around each of the neighborhoods represented by yama and hoko floats (the latter topped with tall halberds), gazing at the floats illuminated by lanterns in the shape of a shogi game piece, and the atmosphere is quite different from that of the main procession. A surprising number of Kyoto residents say they have never seen the procession even once, but probably there are few who have never been to the yoiyama and yoiyoiyama. People have different reasons for attending, and while children bubble with excitement over the stalls selling shaved ice with flavored syrups, small cakes, or the chance to try a water balloon fishing game, there is also much to excite art appreciators. Obviously the magnificent floats, and the sacred items and ornaments that adorn them or are displayed at local community centers, enchant everyone including children and tourists. However, for a limited time there is another attraction to delight art lovers, namely traditional houses where folding screens and other works of art are displayed in parlors with doors and windows open, as is common in summer, for the viewing pleasure of passersby on the street. This tradition is called the “Folding Screen Festival.” Today there are fewer townhouses with large parlors and thus fewer homes taking part, but even when they are not fully open to the public, people can still look for rooms with lights in their latticed windows and peek through at the beautiful items, making some amazing discoveries.

Unfortunately, this year the procession of floats has been canceled and night-time events suspended as countermeasures against the coronavirus. In hopes that Kyoto’s vibrant atmosphere will be restored, in this Nihonga (modern Japanese-style painting) area we present folding screens, all of them large pairs of six-panel works, from the museum’s collection, divided into two terms, the first ending August 23 and the second beginning August 25. We cannot hope to compete with the thrill of the actual Folding Screen Festival, but we invite you to enjoy this somewhat belated MoMAK Folding Screen Festival in the closing days of summer.

#Stay_Connected Karen KNORR, Connoisseurs: Pleasures of the Imagination, 1986-88, ©Karen Knorr

In the spring of 2020, the rapid spread of an unknown new virus forced museums to close their doors worldwide. It was not only museums but also arts and cultural facilities of all kinds, including cinemas, libraries, theaters, and concert halls, which ought to be open to all of society. As they closed one after another, we faced a truly unprecedented situation pervaded with a sense of airless stagnation as time seemed to slow to a crawl.

Over the past few months, with museums unable to function as public spaces for viewing art, there have been wide-ranging efforts to present art to people in diverse ways via the Internet. New ways of connecting to the arts regardless of physical and temporal distance can lead to rethinking and transformation of how we engage with the arts, and this includes museums’ role in the relationship between artwork and viewer. While the creativity and ingenuity of museum staff in bringing art appreciation opportunities online has been truly stunning, many people have surely come to recognize anew the irreplaceability of the experience of actually visiting a museum and seeing works of art in person in its galleries.

A museum is not only a place to encounter works of art, it is also a place to meet other people with diverse ideas and values, share various reactions and impressions, and forge and deepen connections with friends and acquaintances. As you enjoy this exhibition, we hope you will contemplate the various words that could follow this phrase: Stay Connected To…

Auspicious Patterns in Modern Crafts KATO Hajime, Lidded Decorative Jar in Gold Leaves on overglaze Spring Green enamel, 1968

In conjunction with the exhibition Life in Kyoto: Arts in Seasonal Delight, we are pleased to present decorative arts from the museum’s collection that feature kissho-mon (auspicious patterns).

The word kissho has its roots in ancient Chinese culture, and refers to omens or motifs believed to signify great happiness and good fortune. After this cultural tradition was transmitted to Japan, auspicious patterns unique to the country emerged, and were joyfully interwoven into everyday life and customs in various ways. These patterns particularly developed as ornamentation for hand-crafted items used in daily life, and at times the forms of the objects themselves implied happiness and good fortune.

Various auspicious patterns convey a range of meanings such as longevity, prosperity of descendants, and advancement in work and life. These patterns represent the hopes of people living in this world, in the forms of animals, plants, and objects from fantastic worlds, and when they are applied symbolically to utensils and furnishings that decorate spaces and have practical uses, both special occasions and ordinary routines are rendered richer and more vibrant. For example, one of the most commonly seen patterns in Japan is that of pine, bamboo and plum, said to have originated from the Chinese motif known as the Three Friends of Winter, which represents hopes for longevity through the evergreen pine and bamboo and the winter-blossoming plum tree. Meanwhile, the dragon and phoenix, auspicious beasts that symbolized the Emperor and the Empress of China, in Japan took on the meaning of great power and prosperity. Other common patterns include karakusa (lit. “Chinese grasses,” also including flowers), which due to their strong, vibrant life-force represent longevity and prosperity of descendants, and hosoge (arabesque flower patterns) with imaginary flowers incorporating elements of peony, lotus, pomegranate and other blossoms that are themselves considered auspicious and decorate a wide variety of objects. Fukuroku hoko is a well-known East Asian painting motif with deer, bees, bats, and monkeys, which celebrates success in career and life.

Although there is only space for us to exhibit a small number of auspicious patterns here, we hope you will absorb the positive energy that the artists put into these objects and their users derived from them.

Special Exhibit: Spirit of the Primordial Land, a Series of Vessels by Raku Jikinyu (Kichizaemon XV)

Born in Kyoto in 1949, the eldest son of 14th-generation Raku ceramics master Kakunyu, Kichizaemon XV succeeded his father, then ceded stewardship of the renowned family to his own eldest son on July 8, 2019 and retired, adopting the name Jikinyu. After graduating from Tokyo University of the Arts, where he majored in sculpture, Jikinyu studied in Italy at the Academia delle Belle Arti di Roma. In 1981 he became the 15th head of the family, taking the name Kichizaemon. For 450 years, from first-generation master Chojiro to the present, the Raku family has maintained close ties with the tea ceremony. While its distinctive styles, primarily those of black Raku ware and red Raku ware, have been inherited by successive generations, they have pursued ceaseless innovations over the centuries. Jikinyu has been particularly aware of the historic legacy of the house of Raku, and has been active as a creative artist focused on the tea bowl not only as an object but as a contemporary art form imbued with spiritual meanings, philosophical ideas, and aesthetic principles.

This series of vessels was inspired by utensils, masks and other objects from Africa in the special exhibition When Japan's Tea Ceremony Artisans Meet Minpaku’s Collections: Creative Art in Perspective, held at the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka in 2009. The initial title of the series was African Dream, but it was later changed to Spirit of the Primordial Land so as to more clearly reflect its content. The works are a crystallization of Jikinyu’s creative intent to discover and interpret objects inhabited by folk spirit, which served as the sources of imagery, and to engage with them through his own production of vessels. While delving into the primal origins of vessels, Jikinyu eliminated the base that is considered an essential element of a tea bowl, and worked with a wide variety of clays and techniques.

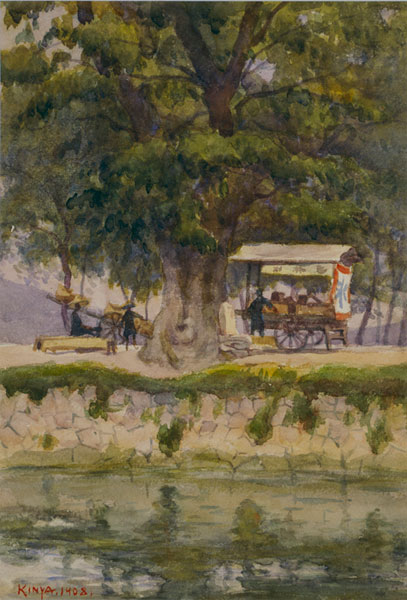

Kyoto Landscapes ARAI Kin'ya, The Bank of the Kamo River, Kyoto, 1908

Kyoto, the capital of Japan for 1,200 years beginning in the Heian Period (794-1192), is home to a rich variety of landscapes. From the Meiji Era (1868-1912) onward, Kyoto scenery has been depicted by countless painters.

In this section, let us take a tour through some of these landscapes as seen in watercolors and prints from the museum’s collection.

At the center of Kyoto is the Imperial Palace, to the immediate southeast of which is the Kawaramachi-Marutamachi intersection. Go north on Kawaramachi-dori Street and you will come to Kojinguchi-dori Street; head east on this street and you will find Kojin-bashi Bridge over the Kamo River. A short way north of Kojinguchi-dori is Nashinoki Shrine, close to the Imperial Palace, and going north on Nashinoki-dori Street you will arrive at Demachi to the northeast of the Imperial Palace. Across the Demachibashi Bridge is the triangular confluence of the Kamo River, to the north of which is the sacred grove of Tadasu-no-Mori next to Shimogamo Shrine. To the east of the Takano River, which flows into the Kamo River, is the village of Jodoji, slightly south of Kitashirakawa in the district of Otagi-gun, and Kumano-Nyakuoji Shrine at the southern end of Tetsugaku-no-michi (the Philosopher’s Walk). To the west of this, Heian Jingu Shrine in Okazaki Park is a building replicating the Council Hall that was at the center of the Imperial Palace during the Heian Period. South of Okazaki Park is Sanjo-dori Street, on which is located Awataguchi, gateway to the Yamashina area. The five-storied pagoda known as Yasaka Pagoda actually belongs to Hokan-ji Temple, south of Yasaka Shrine.

Continue south from here and you will arrive at Tohka Bridge, where Jujo-dori Street crosses the Kamo River. To its southeast is the renowned Fushimi-Inari Shrine. Further to the south is Ogurusu, on the eastern side of the mountain in Okame-dani, Fukakusa, where the rebel samurai general Akechi Mitsuhide met his end.

From here on, the exhibited works lead us on a somewhat impractical course. First we make a sudden leap to the northwest of Kyoto, to the popular tourist destination of Arashiyama around the Katsura River. Past Uzumasa, near Ninna-ji Temple, is Ryoan-ji Temple, famous for its Zen rock garden. From here, make your way back to Nijo Station or Kyoto Station, for which you can depart for Amanohashidate, known as one of Japan’s three great scenic views.

TOMATSU Shomei, Kyoto-Mandala

Born in Nagoya in 1930, Tomatsu Shomei worked on the staff of mass-market photo-book publisher Iwanami Shashin Bunko before beginning an independent photography career in the 1950s. His work, characterized by sophisticated compositions and vivid colors but also posing profound questions about Japan and its people in the postwar era, had a major influence on successive generations of photographers and remains highly esteemed worldwide.

In conjunction with the exhibition Life in Kyoto: Arts in Seasonal Delight on the third floor of the museum, we are pleased to present all 75 photographs in Tomatsu’s series Kyoto-Mandala, from the museum’s collection. While Life in Kyoto focuses on nature, the seasons, and arts that enliven people’s everyday lives, in these photographs Tomatsu’s goal was to focus squarely on the people of Kyoto themselves and their daily life activities. He turned to Kyoto in the 1980s after having similarly documented Nagasaki and Okinawa in the 1960s and 1970s. Tomatsu did not select Kyoto because it was the ancient capital or due to its charming atmosphere, rather he turned a critical gaze on Japan’s cultural “capital,” and by extension Japan as a whole, as the root of tragedies that had befallen Nagasaki and Okinawa. Similar insights can be seen in his masterful late series Sakura (Cherry Blossoms).

When one has viewed the Life in Kyoto exhibition, Tomatsu’s Kyoto-Mandala, and the two works in his Sakura series showing cherry blossoms at the Imperial Palace and at Nijo Castle, what sort of image of Kyoto emerges?

Exhibition Period

2020.07.22 wed. - 10.04 sun.

[First term]7.22 wed.~8.23 sun.

[Second term]8.25 tue.~10.4 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

The Folding Screen Festival

#Stay_Connected

Auspicious Patterns in Modern Crafts

Special Exhibit: Spirit of the Primordial Land, a Series of Vessels by Raku Jikinyu (Kichizaemon XV)

Kyoto Landscapes

TOMATSU Shomei, Kyoto-Mandala

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

2nd Collection Gallery Exhibition 2020–2021 (185 works in all) (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Hours

9:30AM–5:00PM

*July 23–September 22: 9:30AM–6:00PM

*Fridays and August 16: 9:30AM–8:00PM

*Admission until 30 min. before closing

*Opening hours is subject to change, due to the prevention against COVID-19 pandemic. Please check the updated information, before your visit.

Admission

Adult: 430 yen (220 yen)

University students: 130 yen (70 yen)

High school students or younger,seniors (65 and over): Free

*Figures in parentheses are for groups of 20 or more.

Night Discount for Collection Gallery

Adult: 220 yen

University student: 70 yen

*The Discounted admission is only available after 5 P.M. on Fridays

*Admission until 30 minutes before closing.

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

![TSUCHIDA Bakusen, Woman Divers (Right Screen), 1913 [on View: July 22–August 23]](https://www.momak.go.jp/English/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/06/土田麦僊_海女_1913_右隻.jpg)

![TOMIOKA Tessai, Distant View of Mt. Fuji・Autumn View of Kankakei (Left Screen), 1905 [on View: August 25–October 4]](https://www.momak.go.jp/English/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/07/富岡鉄斎_富士遠望図・寒霞溪図_1905.jpg)