Collection Gallery

5th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2022–2023

2023.01.28 sat. - 04.16 sun.

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

In this section, we introduce a number of outstanding works of Western modern art from the museum’s own holdings and deposits. In conjunction with the Kainososho Tadaoto: Crossing Boundaries in Nihonga, Theater, and Film exhibition, currently underway in the Special Exhibition Gallery on the third floor, we are pleased to present a selection of works by Georges Rouault (1871–1958).

Rouault’s steadfast popularity in Japan can be traced to the sizable number of his paintings and prints in Japanese museums and frequent exhibitions of his works. The son of a cabinetmaker, Rouault was born in Belleville, a working-class neighborhood of Paris. At the age of 14, he was apprenticed to a stained-glass maker, and while undergoing this training, he attended a night school for decorative arts. Rouault’s works, distinguished by black contours and colors that shine brightly from within them, are thought to be rooted in these formative experiences.

Rouault later set his sights on becoming a painter and enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts, where he studied with the Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau. Moreau, who Rouault esteemed throughout his life, taught him that art provided an artist with an opportunity to express their emotions rather than imitating nature, and that imagination was essential in the use of color. Rouault embraced these concepts as his creative principles. Although he kept a close friendship with Fauvist painters such as Henri Matisse, a fellow student at the school, Rouault developed his own unique artistic world.

Among Rouault’s favorite motifs were circus people, sex workers, judges, and the life of Christ. Circus-related subjects can be found in about one third of the artist’s works. As is evident from the paintings included in this exhibition, Rouault’s interest in clowns, acrobats, and dancers was rooted in the sense of anxiety they conveyed as people who lived on the margins of society rather than the glamour of performing. At the same time, Rouault recognized that they possessed an inner freedom that was wholly unbound.

With an unblinking view, Rouault expressed the ambivalent nature of human beings in this works that frequently came in for harsh criticism due to their depiction in an ugly and grotesque manner. However, his works also contain profound insights into his subjects. This and his powerful lines and colors continue to resonate deep in contemporary viewers’ hearts. Rouault poured his soul into his works, and in some cases, his depictions extend beyond the picture plane and into the frame.

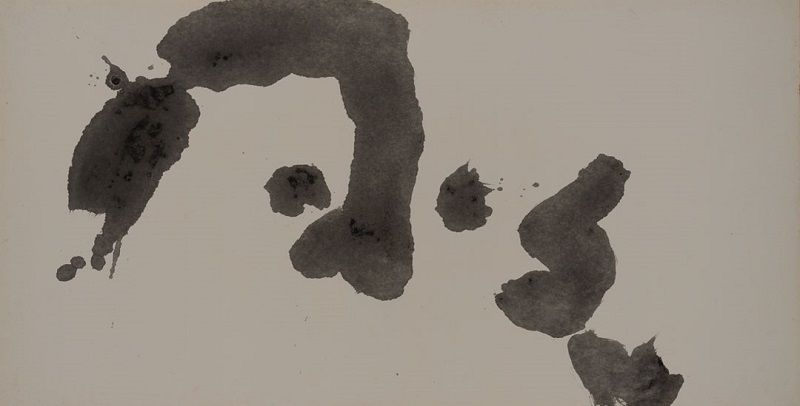

Avant-Garde Calligraphy MORITA Shiryu, Datsu(Emancipation), 1959

As suggested by the debate that erupted between the painter Koyama Shotaro and the scholar Okakura Tenshin after the former published an essay titled Sho wa bijutsu narazu (“Calligraphy Is Not Art”) in 1882, the early Meiji Period (1868-1912) saw a great deal of discussion about whether calligraphy was art or not. Due to influx of Western culture, including the concept of art, Japan developed art institutions that were modeled on those in the West. Until that point, the term shoga (“calligraphy and painting”) signified two distinct parts. For example, at the 3rd Domestic Industrial Exhibition, painting was afforded the highest rank: “Division 2: Art / Category I: Painting.” Calligraphy, meanwhile, was relegated to the bottom: “Division 2: Art / Category V: Printing, Photography, and Calligraphy – 3. Calligraphy.”

At the start of this new era, the Chinese calligrapher Yang Shoujing (known as Yo Shukei in Japanese) brought many rubbings of stone inscriptions to Japan in 1880, enabling calligraphers such as Iwaya Ichiroku and Kusakabe Meikaku to study classical Chinese calligraphy. Among Kusakabe’s students was Hidai Tenrai, who subsequently came to be known as the “Father of Modern Calligraphy.” While studying Kusakabe’s style, Hidai was fervently copied the Chinese classics before eventually evolving a new form of calligraphy. He later published Gakusho sentei, a collection of calligraphy based on his research of the classics, opened the Gakushoin calligraphy school, and disseminated the school’s methodology. The ambitious young people who assembled around Hidai, who adamantly believed that calligraphy was an art form, established the Shodo Geijutsusha organization and published Shodo Geijutsu magazine to explore new calligraphic expressions. Among those associated with the organization were Ueda Sokyu, who emphasized creativity in calligraphy and spawned an avant-garde trend in the medium; Kaneko Otei, who advocated the more approachable medium of modern poetry calligraphy, which combined kanji with kana characters; Teshima Yukei, who originated shosho, a means of expressing a character’s shape to convey its meaning; and Hidai Nankoku (the son of Hidai Tenrai), who created a cutting-edge work of abstract calligraphy called Shinsen sakuhin dai 1: Den no barieishon (Spirit Line 1: Lightning Variation).

Although these activities came to a temporary halt during World War II, after the war five of Ueda Sokyu’s students (Morita Shiryu, Inoue Yuichi, Eguchi Sogen, Sekiya Yoshimichi, and Nakamura Bokushi) formed the Bokujinkai group in Kyoto and greatly expanded avant-garde calligraphy. Through their friendship with abstract painters such as Hasegawa Saburo and Yoshihara Jiro, the group’s members explored creative qualities of calligraphy and formed close ties with painting. Their work was also highly acclaimed abroad, enabling them to show their calligraphy in numerous international exhibitions. Although calligraphy is rooted in the written character and has a practical aspect, making it different from painting, the tension and dynamic brushwork that arises from the characters is what gives avant-garde calligraphy its charm. At the same time, there were some calligraphers, including Hidai Nankoku, who set out to evolve freeform calligraphy that defeated the constraints of characters, illustrating the fact that it is no easy task to sum up avant-grade calligraphy.

Crafts and Designs by Painters IWAMURA Tessai / KAMISAKA Yukichi / TAKASE Kozan / FURUICHI Unosuke / YAMAGA Seika / YAMADA Rakuzen I / Design: KAMISAKA Sekka, Flower-Decorated Cart, Early Showa Era (c. 1926-40)

In conjunction with the Kainosho Tadaoto: Crossing Boundaries in Nihonga, Theater and Film, we are pleased to present a selection of works from the museum collection that deal with the theme of crafts and designs made by painters. In addition to designs devised by the artists, there are ceramics and other crafts for which they supplied painting.

When artistry was established as a feature of craft-making, it became natural for individual artisans to oversee the entire process, from design to production. However, at an actual craft production site, the system often involves a division of labor or collaborative effort, resulting in outstanding works that are based on a fusion of advanced techniques and experience.

While some of these works were made by painters associated with the Rinpa school, active during the Edo Period (1603-1868), there were also specialist painters who, with the arrival of the Meiji Period (1868-1912), devoted themselves to crafts and design. This trend was rooted in a national effort to create crafts and designs that were in keeping with the new era by promoting craft exports as part of the government’s industrial development policy and incorporating painters’ design skills. During the late Meiji and Taisho Period (1912-1926), the Western-style painters Asai Chu and Kamisaka Sekka established the Yutoen and Kyoshitsuen research institutes with Kyoto-area artisans. The institutes flourished by studying design that referenced styles such as Art Nouveau and the Rinpa school, and organizing exhibitions.

Meanwhile, the Kyoto ceramic artist Kawai Unosuke engaged in numerous collaborations with painters. These paintings are filled with a joy that has the quality of a hobby. In the textile field, some painters’ designs were made into highly skilled works, such as the tapestries on display here by preeminent Western-style painters like Foujita Tsuguharu, Sakamoto Hanjiro, and Oka Shikanosuke. Other examples of painters’ artistry include leatherwork by Kamisaka Sekka’s elder brother, the Nihonga (Japanese-style) painter Kamisaka Shoto, and ceramic paintings by Motonaga Sadamasa, a member of the Gutai Art Association.

Three Kyoto Painters: ITO Yasuhiko, HASEGAWA Yoshio, and SHIMOTORI Yukihiko HASEGAWA Yoshio, Forest of Tadasu, 1905

Although various theories around regional characteristics in Japanese modern art have been advanced, there is no cut-and-dried answer. Is there something identifiably Kyoto-esque about yoga (Western-style oil and watercolor paintings)? When it comes to Nihonga (Japanese-style painting), it is certainly possible to cite fundamental qualities such as the use of live sketching, which began with Maruyama Okyo in the early modern period, and the innovative approach and legacy of Takeuchi Seiho in the Meiji era. However, in terms of yoga, limited as it is to the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taisho Period (1912-1926), it is tempting to say that the Meiji painter Asai Chu (1856-1907) was the only figure who played such a central role. Asai was actually born in Edo, but he spent five years in Kyoto late in his life, and after forging close friendships with local painters, artisans, and literary figures, cultivated a variety of supple artistic expressions that transcended the framework of fields such as painting, crafts, literature, and science. These activities subsequently influenced the direction of Kyoto painting, crafts and design.

Among the many artists who studied with Asai in Kyoto were Ito Yasuhiko (1867-1942) and Hasegawa Yoshio (1884-1942). Ito was born into a family of priests at Kumano-nyakuoji Shrine in Kyoto, and Hasegawa was the son of a wealthy farming family in the city’s Higashi Kujo area. Both men died exactly 80 years ago last year. Maintaining a reasonable distance from art-world trends in Tokyo, the artists might be seen as quintessentially Kyoto painters in as much as they freely and fluidly devoted themselves to the pursuit of beauty in the city. Meanwhile, although Shimotori Yukihiko (1884-1982) was born in Tokyo, his admiration for Asai led him to move to Kyoto, where he emerged as a guiding figure in the local art world. He died 40 years ago last year.

This exhibition features the works of these three Kyoto painters, Ito Yasuhiko, Hasegawa Yoshio, and Shimotori Yukihiko, and marks the anniversary of their respective passings.

Exhibition Period

2023.1.28 sat. - 4.16 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

Selected Works of Western Modern Art

Avant-Garde Calligraphy

"Thread" works - Textile and Art

Crafts and Designs by Painters

Three Kyoto Painters: ITO Yasuhiko, HASEGAWA Yoshio, and SHIMOTORI Yukihiko

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

5th Collection Gallery Exhibition 2022–2023 (90 works in all) (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Hours

10:00 AM – 6:00 PM

*Fridays: 10:00 AM – 8:00 PM

*Admission until 30 min before closing.

*Opening hours is subject to change, due to the prevention against COVID-19 pandemic.

Please check the updated information, before your visit.

Admission

Adult: 430 yen (220 yen)

University students: 130 yen (70 yen)

High school students or younger,seniors (65 and over): Free

*Figures in parentheses are for groups of 20 or more.

Collection Gallery Free Admission Days

January 28, February 4, April 15, 2023

In conjunction with...

Jan 28 - Apr 16, 2023

Modern Finnish Ryijy Textiles from the Tuomas Sopanen Collection

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)