Collection Gallery

1st Collection Gallery Exhibition 2018–2019

2018.03.14 wed. - 05.27 sun.

The World of Kanno Seiko: 30 Years after the Artist's Death KANNO, Seiko Equation which is filled Everywhere with Indifferential functions 1988

Kanno Seiko was born in Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture in 1933.

After graduating from the Faculty of Education at Fukushima University with a major in art, Kanno began making abstract paintings. She moved to Kansai region in 1958 because of her husband's work transfer, and in 1964, Kanno became involved with the Gutai Art Association, an abstract art group led by Yoshihara Jiro. (She became an official member in 1968.)

Deeply interested in poetry, music, philosophy, physics, and mathematics, Kanno's paintings were strongly influenced by this worldview. In the late '60s, Kanno arrived at a unique style characterized by fine, delicate vertical and horizontal lines, and recurring structures.

After the Gutai group was dissolved in 1972, Kanno continued showing her work in solo exhibitions and the Ge exhibition (dedicated to work by Kansai-based contemporary artists), and strove to add depth to her artistic expressions. However, in 1988, she suddenly collapsed and died at her house in Nagaokakyo, Kyoto, at the age of 54.

Following her death, Kanno's family made donations of her works to the museum. On this occasion, the 30th anniversary of the artist's death, we present these works and take a look back at Kanno's career.

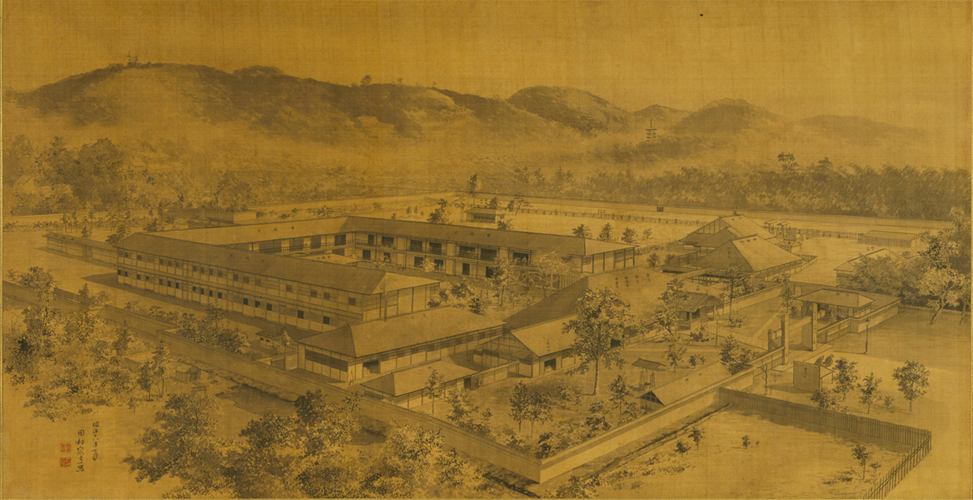

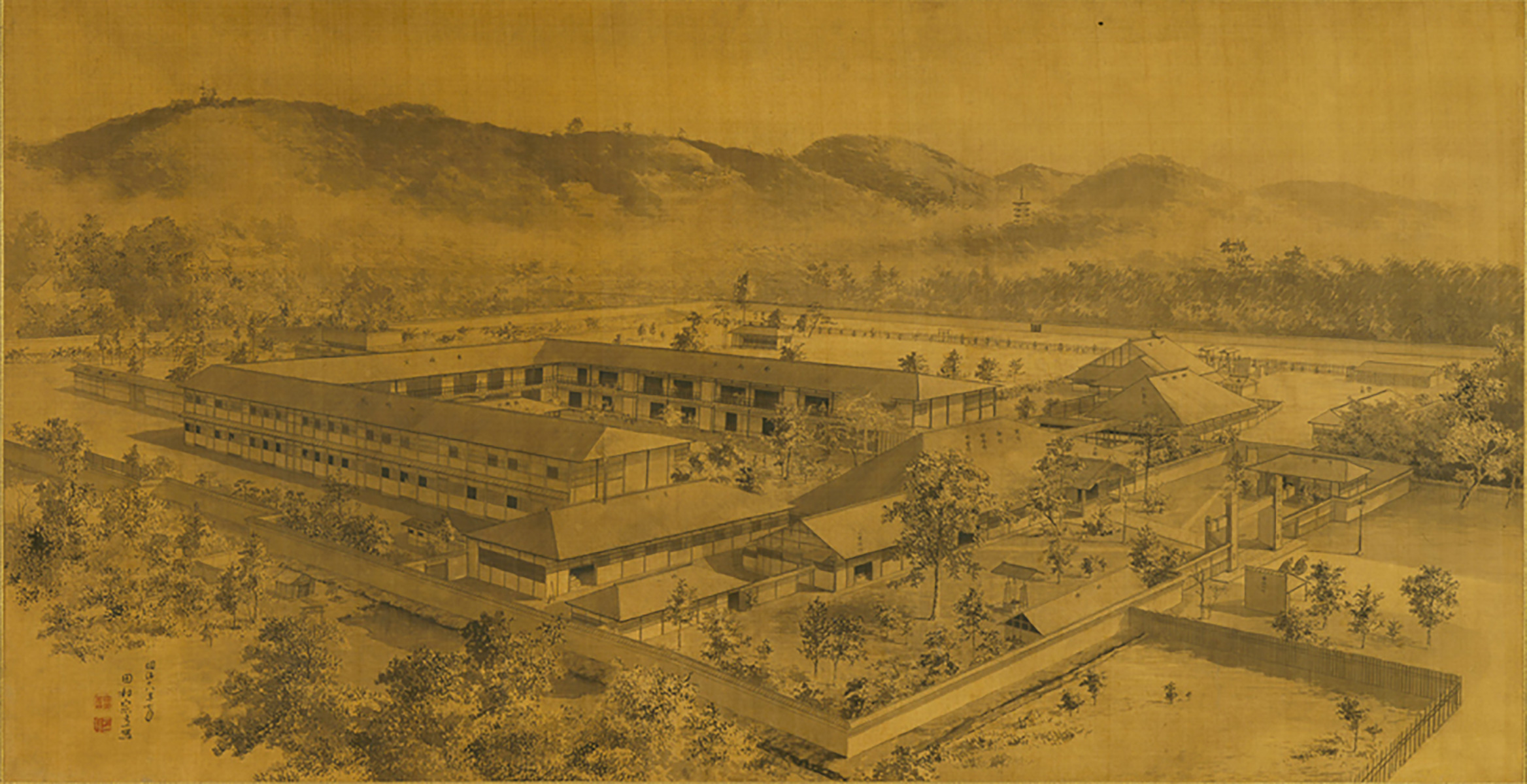

Special feature: Tamura Soryu (1846-1918) TAMURA, Soryu, Pox Hospital in Kyoto, 1885

Tamura Soryu, a pioneer in the Kyoto Western-style painting scene, was born in the village of Kamikawachi, Funai-gun, Kyoto (in the vicinity of what is now Funaoka, Sonobe-cho, Nantan City) in 1846. (He was also known as Juhhoumei and Tamura Gessho). Developing a fondness for painting as a child, he studied Nanga painting with Taigado Seiryo and Buddhist painting with the artist-monk Taigan at Rokakku-do in Noman-in Temple. After realizing that "pictures could show real things," Tamura discovered that all objects have shadows as he undertook a series of experiments.

In about 1869 or 1870, Tamura first became aware of oil painting and, thinking that a knowledge of English would be necessary to study the technique, he began to study the language at Kyoto Prefectural Junior High School. Around the same time, he found work painting anatomical charts at a hospital in Shoren-in Temple, located in Awataguchi, and after obtaining some oil-painting manuals from foreign people he met at the school and hospital, taught himself the technique.

Tamura began working as an instructor at the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting when it opened in 1880. Then, after Koyama Sanzo retired from his post as a full-time teacher of Western painting, Tamura was appointed as a third-class teacher and carried on in Koyama's footsteps. After quitting the school in 1889, Tamura established the Meiji Art School, and devoted himself to training younger painters. His students included outstanding Western-style painters like Hara Busho and Ito Yoshihiko.

To mark the 100th anniversary of Tamura's death, we present some of the artist's Nihonga (Japanese-style paintings) and oil paintings as well as various related materials such as a notebook he used for his English studies, a sketchbook containing various attempts at depicting "real things", and a letter of appointment for his job at Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting.

Spring Scenery in Japanese-style Painting KAWAMURA, Manshu Spring Scene in the Ancient City, Nara, 1918

Japan is a country with four seasons. Since ancient times, Japanese people have expressed their love for each season in poetry, prose, and painting. In the Nihonga section of this edition of the collection exhibition, we present a selection of works that depict seasonal beauty with a particular emphasis on scenes and manners associated with spring.

When we speak of spring, the first thing that comes to mind is cherry blossoms. We hope that you will enjoy comparing a variety of paintings by modern Nihonga artists such as Tomita Keisen's Cherry Blossoms at Daigo, which depicts the cherry trees at Daigo-ji Temple. The temple is especially renowned for the daimyo Toyotomi Hideyoshi's (1537-1598) cherry-blossom viewing parties.

Since the second half of the exhibition, beginning on April 24, coincides with the scattering of the cherry blossoms, we present works depicting flowers such as peonies and poppies, which are associated with "early summer" in the world of poetry.

And while we're on the subject of flowers, Kyoto was once home to Shirakawame ("women from the Shirakawa area"). Clad in elegant attire, these women would come to the city to peddle flowers that had been harvested in the Shirakawa River Basin in a tradition dating to the Middle Ages. Today, Shirakawame are only seen at events like Jidai Matsuri (Festival of the Ages), but until World War II the women were a common sight. Bringing seasonal fragrances from the country to the city, they were depicted by many painters as the embodiment of each season's beauty. We hope that you will enjoy these works along with the diverse assortment of flowers.

The Relationship between Industry and Art Felice "Lizzi" UENO-RIX, Wallpaper (Vicia), Before 1928

In the wake of the Industrial Revolution, which occurred in Great Britain in the late 18th century, traditional handicrafts were largely replaced by machine manufacturing and mass production, leading to major changes in people's lifestyles and the social structure. In this modernization process, the role and status of art in industry evolved to reflect the ideas and values of the times. In this exhibit, we focus on innovations in applied arts, with a particular emphasis on artists who set out to improve various designs.

After being invited by Josef Hoffmann to join his Vienna Workshop in 1917, Felice "Lizzie" Rix began making decorative designs for a wide array of crafts, including textiles, ceramics, glassware, and cloisonné. Her printed designs, so-called "Rix patterns," received a great deal of acclaim. Rix's marriage to the architect Ueno Isaburo led her to come to Japan. While in the country, she and created designs for the Gunma Prefectural Institute of Crafts, which the German architect Bruno Taut also involved, the Kyoto Municipal Institute of Dyeing and Weaving (now the Kyoto Municipal Institute of Industrial Technology and Culture), and in the 1950s, Inaba cloisonné, which is associated with Kyoto's Shirakawa district.

In the 1980s, the noted kitchenware manufacturer Alessi introduced a series of "Tea & Coffee Piazzas," which the company commissioned 11 architects to design. The Italian word "piazza" means public square, and the architects' ideas were earnest attempts to deal with the theme of people's relationships with the city. Tinged with a playful and humorous spirit, the tableware was designed to decorate the dining table on a daily basis.

Photography, which was invented in the 19th century, spread quickly and was commercialized and industrialized in a variety of ways. These included travel photographs, which became popular mementos from various sightseeing spots, and reproduction techniques, such as printing, which made it possible to mass produce photographs.

At the same time, there were artists dispassionately observed people's roles in industry and society, and used the contradictions they discovered as the theme of their work. Marcel Duchamp's readymades, commercial goods that he exhibited as artworks, upended preconceived notions of art as something that was necessarily the product of the human hand. With her hand-knitted "paintings," which emulate machine-knitting, Rosemarie Trockel eliminates all traces of the hand while taking a critical view of modern society, in which the act of knitting has traditionally been associated with women.

The Beauty of Handwork TSUISHU, Yozei XX, Covered Box and Inkstone Box with Folding Screen Landscape , 1918

From the mid-Meiji to the early Showa Period, Japan honored artists by designating them as Imperial Household Artists. After World War II, a similar system was developed in which artists were named holders of Important Intangible Cultural Properties (or Living National Treasures).

Imperial Household Artist was an honorary lifelong title conferred on outstanding artists as a means of promoting art under the patronage of the Imperial Family or Household. The first ten artists were appointed in 1890, and the last group was selected in 1944. Over the years, a total of 79 people were honored on 13 occasions. The Important Intangible Cultural Property system, which was established in 1955, is a governmental means of designating and authorizing arts and crafts in recognition of certain traditions (Intangible Cultural Properties) and the individuals and groups that have attained a high level of mastery in them.

As these systems suggest, Japan has a long history of valuing handwork. This is not limited to the world of arts and crafts, but is also evident from the fact that manufacturing is viewed as an important feature of Japanese culture. Handwork has been passed down, updated, and refined throughout the country's history. Even in the modern era, however, handwork has at times been seen as highly significant (for its transcendental craftsmanship), while at other times, it has been disavowed (for an overemphasis on technical skill) as a reflection of changing values.

In this exhibit, we present the work of 15 artisans, including the Imperial Household Artists Akatsuka Jitoku, Itaya Hazan, and Shimizu Nanzan, who were active in the Nitten (Japan Art Exhibition) and Japan Traditional Arts Crafts Exhibition. They produced excellent works with their highly accomplished skills and they are also considered to be central figures in arts and crafts.

The Kawakatsu Collecion of Ceramic Works by Kawai Kanjiro KAWAI, Kanjiro, Vase with Flower Design and Iron and Cinnabar Glaze, 1935

The Kawakatsu Collection, which includes a grand-prize winning piece from the 1937 Paris International Exposition, constitutes the most substantial public collection of Kawai Kanjiro's works in terms of both quality and quantity.

The collection was donated to the museum by the businessman Kawakatsu Kenichi in 1968. When a museum curator went to see Kawakatsu's huge collection of Kawai's works, which covered an entire floor of his house, he said, "Choose as many as you like." In the end, 415 items were selected. Along with three pieces that Kawakatsu had previously donated to the museum and seven others that were subsequently added to address a lack of Kawai's early works, the collection eventually totaled 425 works. Made up of important works by the artist, stretching from his first efforts, which were modeled on Chinese porcelain, to his final pieces, made after his involvement with the Mingei movement, the collection is truly a chronological encyclopedia of Kawai's ceramics that spans his entire career.

Kawakatsu (1892-1979), who assembled the collection, worked as the advertising manager at the Tokyo branch of Takashimaya Department Store as well as serving as the store's general manager, and the senior managing director of the Yokohama branch. In his role as a member of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry's craft examination committee, he also strove to foster craft designs.

Kawai's long friendship with Kawakatsu began when he went to meet the artist at the station when Kawai traveled to Tokyo for a meeting regarding the 1st Creative Ceramics Exhibition, which was held at Takashimaya in 1921. Immediately sensing that they were kindred spirits, Kawakatsu began collecting Kawai's works. Reminiscing about the collection, Kawakatsu said, "It wasn't merely based on my personal taste. Sometimes Kawai would make works for the collection and he also chose lots of pieces for it." He added, "It was the crystallization of our friendship."

Western Painting of the Meiji Period (Held in Conjunction with the 150th Anniversary of the Meiji Period Exhibition)

The Meiji Period (1868-1912) was an era in which Japan endeavored to become a modern state. In Western painting, which had entered the modern era somewhat sooner, the invention of photography inspired painters to create highly innovative and individualistic expressions that could only have existed in painting.

In 1874, the exhibition that would later come to be known as the 1st Impressionist Exhibition was held in Paris. This corresponded to the seventh year of the Meiji Period, not long after the samurai era had come to a close. Spurred on by Eugène Boudin and other artists who were painting outdoors, the Impressionists focused on imbuing their canvases with dazzling natural light and the overall ambience of a scene. Camille Pissarro and Pierre-Auguste Renoir were among the movement's most notable figures.

In the 1880s, Paul Signac and others developed the Impressionist technique of expressing light through the layering of primary colors in their Pointillist paintings. This movement came to be known as Neo-Impressionism.

In 1888, a group of artists called the Nabis emerged who focused on pictorial structure, an area that had previously been governed by color and form. Works by Édouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard, and others presaged the rise of abstract painting at the beginning of the 20th century.

In 1905, artists such as Maurice de Vlaminck entrusted their emotions to color and painted with violent brushstrokes in a movement known as Fauvism. At this point, painting had completely become a means of expressing the artist's subjective views.

In this section, we present works from the Meiji Period and Western painting of the same era.

Exhibition Period

2018.03.14 wed. - 05.27 sun.

Themes of Exhibition

The World of Kanno Seiko: 30 Years after the Artist's Death

Special feature: Tamura Soryu (1846-1918)

Spring Scenery in Japanese-style Painting

The Relationship between Industry and Art

The Beauty of Handwork

The Kawakatsu Collecion of Ceramic Works by Kawai Kanjiro

Western Painting of the Meiji Period (Held in Conjunction with the 150th Anniversary of the Meiji Period Exhibition)

[Outside] Outdoor Sculptures

List of Works

1st Collection Gallery Exhibition 2018–2019 (167 works)(PDF)

Free Audio Guide App

How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)

Free Audio Guide App How to use Free Audio Guide (PDF)